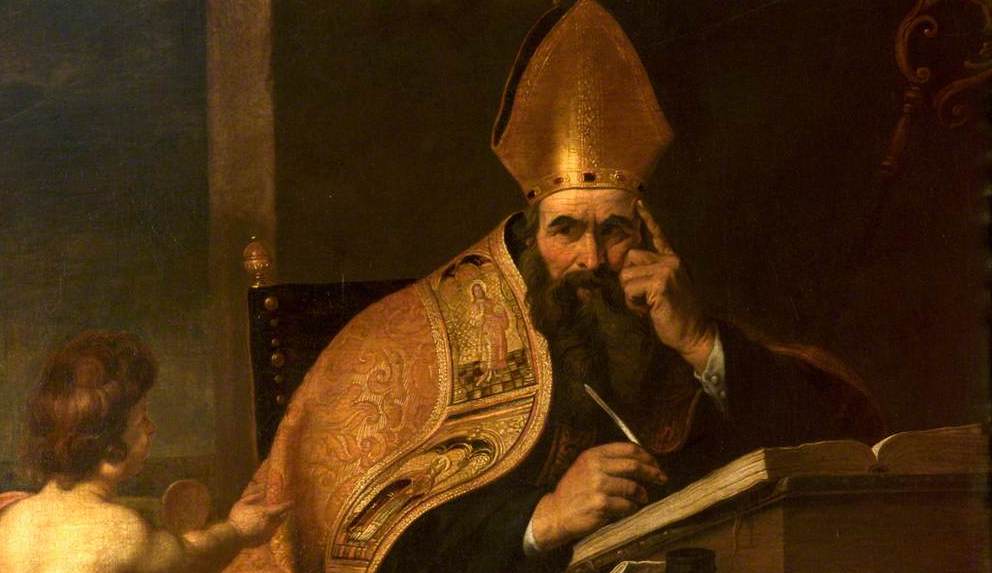

What do we make of Augustine? The theologian Bernard McGinn once quipped: "If all philosophy is a footnote to Plato, all theology is a footnote to Augustine." This is a fine place to begin. After all, the doctrine of Original Sin was indelibly shaped by the great saint who struggled mightily with his intense sexual desire and sought to explain it in part through our first parent's sin, passed down to us all. And of course, the western church has called Augustine the Doctor of Grace, because he never tired of reminding his parishioners and readers of our helplessness without the work of the gift of grace in our lives.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: