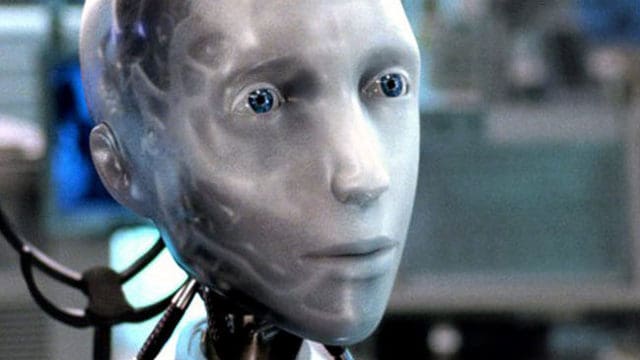

Last year I co-authored a book with Robin Phillips about life in the digital age. The potential implications of what is imprecisely called artificial “intelligence” on our humanity was a theme throughout the book. Recently, Robin thought it would be interesting to see what LLMs had to say about our book collaboration. Here’s what ChatGPT pumped out.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: