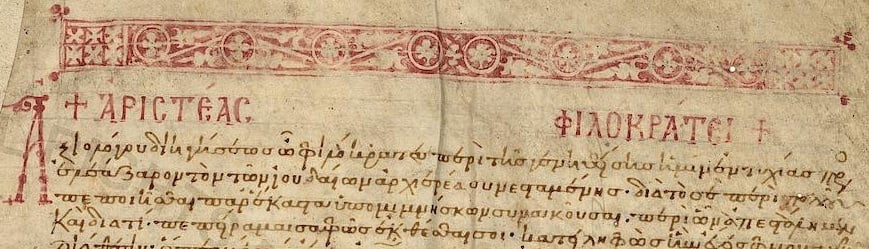

Once upon a time in Hellenistic Alexandria, a number of translators (but were there seventy of them?) gathered together to translate the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. Known as the Septuagint, the result is a bit of a mystery for most church-going Christians. But a better familiarity with the Septuagint would be good for us for a number of reasons, argue scholars Greg Lanier and William Ross, who have devoted significant attention to this text. The vision for making the Septuagint more accessible for the rest of us—pastors, scholars, and regular Christians in the pews—is behind their new co-edited volume, The Authority of the Septuagint: Biblical, Historical, and Theological Approaches (IVP Academic, 2025).

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: