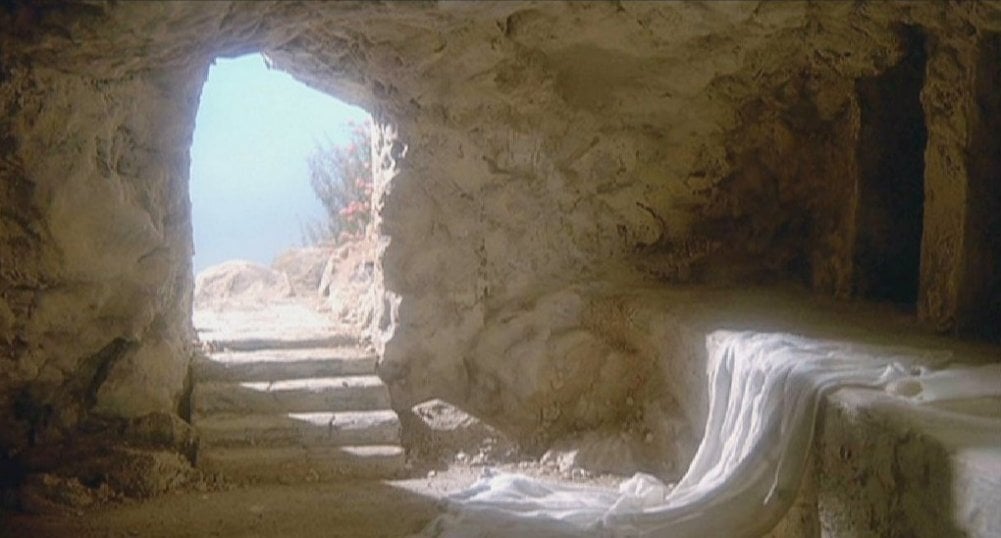

Death casts a shadow over life and, even before our last hours, its presence is already known to us. When we die, death strikes its great final blow, yet we all experience it in countless lesser ways before this time. Traces of its hand are felt throughout our lives, sometimes in a faint cold touch and other times in a cruel pinch. Death strips us of our faculties, it cuts us off from others, it afflicts us with pain, it terrorizes and menaces us, it closes down our bodies, spreading its entropic grip throughout their limbs and organs. Behind innumerable guises—of sickness, disease, infirmity, frailty, distress, disability, pain, bereavement, or ageing—it is the great dread enemy of Death and of Satan, who once wielded its power—that we encounter.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: