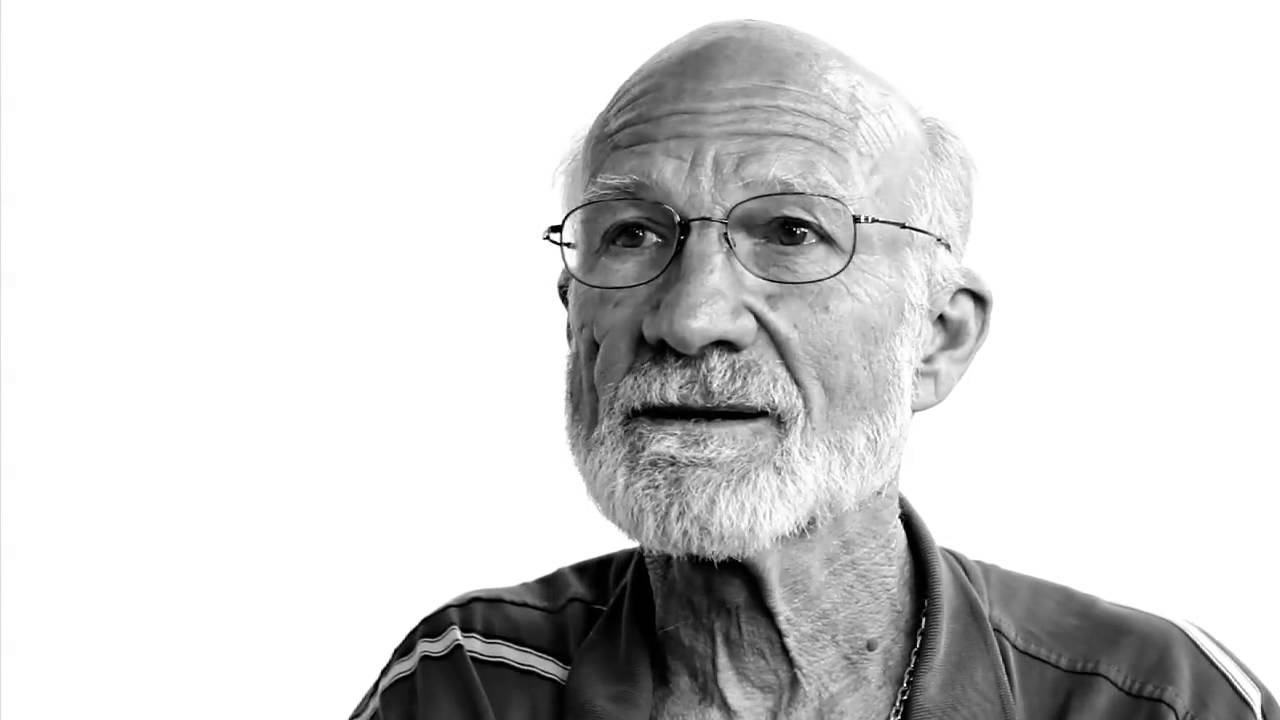

Brad East

Brad East (PhD, Yale University) is assistant professor of theology in the College of Biblical Studies at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. He is the editor of Robert Jenson’s The Triune Story: Collected Essays on Scripture (Oxford University Press, 2019) and the author of The Doctrine of Scripture (Cascade, 2021) and The Church’s Book: Theology of Scripture in Ecclesial Context (Eerdmans, 2022). His articles have been published in Modern Theology, International Journal of Systematic Theology, Scottish Journal of Theology, Journal of Theological Interpretation, Anglican Theological Review, Pro Ecclesia, Political Theology, Restoration Quarterly, and The Other Journal; his essays and reviews have appeared in The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Comment, Commonweal, First Things, The Hedgehog Review, Living Church, Los Angeles Review of Books, Marginalia Review of Books, Mere Orthodoxy, The New Atlantis, Plough, and The Point. Further information, as well as his blog, can be found at bradeast.org.