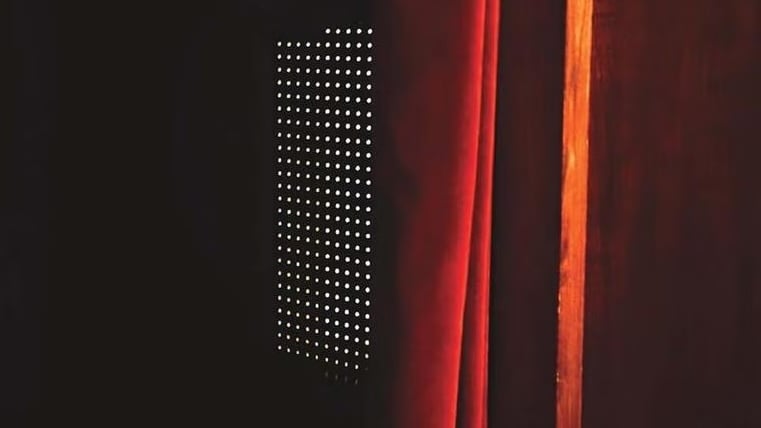

One of the more interesting books to appear last year was James M. O’Toole’s For I Have Sinned: The Rise and Fall of Catholic Confession in America. It traces the development and diminishment of the sacrament of penance in the Catholic Church, expressed in the act of regular confession and embodied in confessional booths inside many church buildings. The book provides a fascinating look at what became one of the most identifiably Catholic practices in America in the middle of the last century, and then the freefall that followed—such a stunning numerical decline that it makes the cultural ethos of confession’s heyday seem like news from a foreign land.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: