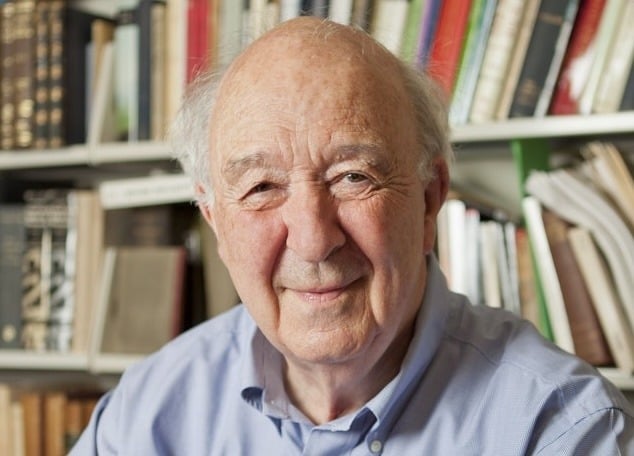

Peter Brown. Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History. New York: Princeton University Press, 2023. 736 pp, $45

Saint Augustine, Peter Brown, and I gathered at a cozy coffee shop on Princeton’s Nassau Street most evenings in the spring of 1999. While I had a coffee in hand and comfortably nestled in a leather chair, St. Augustine shared wisdom on shaping my loves for God. Peter’s warm voice and thoughtful tone drew me in as he unraveled the context, narrative, and theological concerns of this great Doctor of the Church. In those magical late hours, we became fast friends.

Well, almost.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: