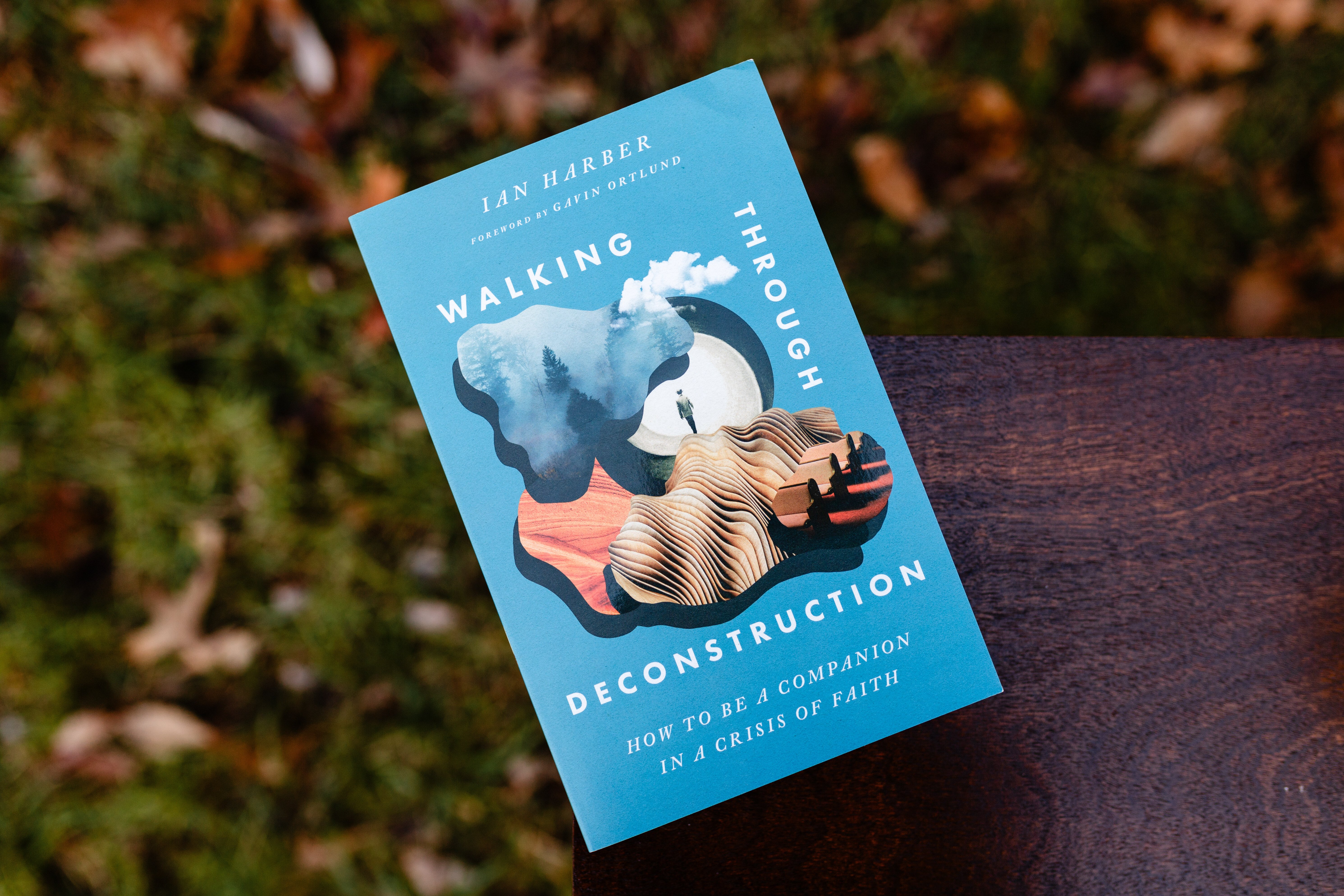

In the conclusion to his new book, Walking Through Deconstruction: How to Be a Companion in a Crisis of Faith (IVP, 2025), Ian Harber powerfully and beautifully reflects: “No matter what doubts, sins, and sufferings come our way, Jesus is inviting us to come to him. God is renewing the world, reconstructing the world that Satan, sin, and death deconstructed, rescuing us from the crisis that is our lives, and giving us everlasting peace.”

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: