One Year Later: Reflecting on Evangelicalism’s Six-Way Fracturing

July 12th, 2022 | 18 min read

Skyler Flowers also contributed to this essay.

Reflections on the Six Way Fracturing of Evangelicalism a Year Later

Critical Race Theory.

Afghanistan.

Verdicts in Floyd and Arbery cases.

Kyle Rittenhouse.

Vaccine Mandates.

Russia invades Ukraine.

Roe v. Wade overturned.

Uvalde school shooting.

#SBCtoo

A year ago, we observed that the same cultural moments are interpreted vastly differently by a wide swath of Americans who otherwise share similar religious commitments. These moments served as nationwide diagnostic tools that led to us outlining a six-way fracturing occurring in American Evangelicalism.

Since that article, Christians in America have continued to ride the cultural roller coaster of events that spark media attention and discourse. Understanding the reactions to these events and the subsequent online discussion through the fracturing framework has helped us to see the reality of these lines, but also how they have deepened, shifted, become more apparent, and more complicated. For instance, as we will show, even some in non-Christian religions have begun to identify as evangelicals. The term “evangelical” continues to evolve. It is in light of this facet that we believe it is appropriate to return to the rubric and revisit a number of things from last year’s article.

Reflections on The Fracturing

As many shared when interacting with our original article, the fracturing that has occurred in the last few years has been something largely felt and observed at the micro and macro level without formal expression. The historic missional and theological bonds that held together churches, denominations, and organizations still tape them together, but the lines behind the tape are more clearly visible. Just in the last year, the extent to which differing political, cultural, socioeconomic, and theological values have been expressed has become more vocally exposed.

As a result, these organizations have felt at times like they will burst at the seams, the tape no longer holding. So far, national organizations, though more complex in their configuration, have remained sturdy despite fractures, while the local level has seen far more movement. Some of this movement will be explored more particularly below, but it is worth stating here what we failed to state last year: the six way fracturing is meant to be used as a diagnostic tool rather than a reductive weapon used against people. Too often in today’s rhetoric people are reduced to labels, making them and their ideas easily dismissable. Organizing the observations we have seen in our churches and in broader circles into six categories should hopefully serve to foster conversation as we are more easily able to place our finger on the places of real disagreement, while affirming the places of agreement.

Moreover, the spectrum of the fracturing exists more as a sliding scale than a set rubric. This is essential for understanding the current evangelical landscape. The issues that our culture confronts us with cause movement to the right or left in each instance. Just reading through the brief list of major cultural moments in the last year, the reader will likely feel a tightness in their chest for each one – visceral emotions – but those emotions will be provoked in different directions on each one. This is determined by political, personal, familial, and theological commitments, many of which are unconscious or subconscious. Nevertheless, they shape us and move us – possibly from one subset to another over time.

In light of this, a few observations are in order concerning the fracturing itself, before considering the implications this might have organizationally.

Reflections on the Six Categories and Fault Lines

Overall, it can be said that the definitions we offered a year ago for each subset still holds.

- Neo-Fundamentalist Evangelicals (1’s) still are defined by a deep concern for political and theological liberalism, asserting a more courageous and vocal stance against the movements of culture from a firm biblicism.

- Mainstream Evangelicals (2’s) still find themselves largely motivated by mission but are more disturbed by the culture’s turn against Christianity than internal threats.

- Neo-Evangelicals (3’s) still see themselves as the winsome and moderate alternative to the rhetoric they see from 1’s and 2’s, willing to critique both their left and their right, leaving them feeling largely adrift.

- Post-Evangelicals (4’s) have even more powerfully rejected evangelical labels with the further exposing of abuse, corruption, and hypocrisy in the church. They find themselves in a place of “deconstruction,” by which they mean the healthy practice of deconstructing the cultural idols that had been added to the expressions of Christianity they previously moved in. Such deconstruction is viewed externally as the deconstruction of Christianity itself, leading groups 1-2, possibly even some 3’s, to view them as on the path to dechurching or deconverting.

While the definitions of each subset of the fracturing still appear to hold, what might have changed are the individuals who find themselves in each category. Before addressing the particulars of the movements, we must first turn to consider each group’s ability to move generally.

Viscosity and Fluidity

Some of the groups have increased in viscosity while others have decreased. Neo-Fundamentalist Evangelicals (1s) have maintained the highest viscosity, remaining well rooted in their deep concerns for theological and political liberalism. Mainstream Evangelicals have seen to be more fluid and have a lower viscosity than many other groups. We saw this group have voting solidarity with the Neo-Evangelical group in the 2021 SBC presidency vote and then throughout the “winsome” debates over the last couple of months take increasingly strong turns back towards perspectives and attitudes that we usually only see from Neo-Fundamentalists. This might be seen in James Wood’s article on Tim Keller and the subsequent reaction to it in First Things. The center of mass of Neo-Evangelicals has remained fairly constant and viscous but a minority of this group has moved a little closer to the 3.5-3.9 range, particularly among minority leaders troubled by apathy towards their animating concerns. We perceive Post-Evangelicals to remain a low viscosity group with a lot of fluidity particularly once one crosses into 4.1+ territory.

After we published originally we realized that the dechurched weren’t just 5’s and 6’s but there was also a relatively large population of sub-1’s whose syncretism with the secular right became so strong that they left the church. We have been working on some yet-to-be published research on dechurching and the picture is a lot more complex than what we had initially thought but we aren’t free to elaborate on that just yet. Suffice to say dechurching, disenculturation, and deconstruction are three unique ideas whose Venn Diagram has some overlap but also have their own unique characteristics.

Movements Between Groups

Understanding their willingness to move, the movements themselves gain clarity. The reader who read the original article in 2021 and identified with a 2-2.5, might now read it again and find themselves a firm 2. Likewise, they might find themselves to be a 3 or 3.5 now. Where a person perceives the excesses and threats of evangelicalism to be can usually predict where and how they will move between these groups. One major difference that can be seen between last year’s article and this one is the lack of emotions towards Trump driving one’s placement. The deep reactions to this one person and continued political turmoil that followed the 2020 election may have caused someone to be one whole number to their right or their left past where they normally would be. With Trump less in the news cycle, people seem to have settled back into their more natural disposition. Still, while the numbers have remained stable with movement between them, whether this is a fracturing in “evangelicalism” has come under question.

The six categories that we outlined were framed as six subsets of the evangelical landscape. At the time, three of the subgroups (#s 1-3) still considered themselves part of broader evangelicalism, while the final three categories (#s 4-6) had definitively broken away. A year later, it appears that the boundaries of the big tent have further eroded. Many who trend toward the conservatism of 1’s define themselves less as evangelicals, seeing it as a term more closely associated with an unhappy alliance with broader culture. Essentially, they believe that the big tent does not allow for the type of cultural critique that is needed in the present age. The movement of some 1s out of evangelicalism is compounded by the more extreme movement by some in the conservative direction into dechurching. Whereas before we framed dechurching as exclusively occurring in the 4-6 range, it is clear now, both qualitatively and quantitatively, that there are off-ramps out of the church in both conservatism and liberalism extremes.

On the other side, 3’s have found themselves largely pulled by the two poles. Many 3’s are likely uncomfortable with some of the alliances forged by 4’s in the cultural space and continue to see the need for Christian critique of American culture. However, in the 3 mindset, the failure of the conservative pole to adequately identify which idols it is susceptible to has left them disappointed and dissatisfied with the makeup of evangelicalism. For some, they find themselves pulled more into the range of 2’s. For many of the higher profile 3’s, this has led them to reject evangelicalism as untenable, even unhelpful, moving more into the range of 4’s.

The movements of these two groups (1’s and 3’s) have led to a new fault line for 2’s. With boundaries tightening, many 2’s have allied themselves closer with 1’s. Though they may feel uncomfortable with some rhetoric or do not share quite the same level of heat over certain issues (like CRT), they do not desire the distance 3’s do from their more conservative brothers and sisters. To do so would be to distance themselves from family, churches, and voices that largely shaped them in formative periods. Even more, they do not see 3’s as sufficiently outspoken on the important theological commitments of sexual identity, gender identity, and abortion that motivate 2’s. In their mind, at best, 3’s lack the courageous fortitude to speak out against the culture and prefer the cultural issues that garner them favor from the broader culture, and, at worst, 3’s secretly and deceptively do not share traditional Christian beliefs on these issues. On the 3-side of the fault line, at best, they see a similar lack of fortitude in 2’s unwillingness to repudiate extreme factions in conservatism, and, at worst, they see 2’s as informally committed to a Christian nationalist, predominantly white, and largely patriarchal worldview.

In light of these movements and shifts in fault lines, it serves us now to reflect on the most likely scenarios that will play out in churches and organizations on the personal level.

Reflections on The Future of Evangelicalism

In our original article we theorized that anglo-centric evangelical churches were sorting themselves into three types of churches: type A (primarily 1s and 2s), type B (primarily 2s and 3s), and type C (primarily 3s and 4s). We believe this sorting is part way done and depending on the context will take another 2-5 years to fully flesh itself out.

This brings up a bigger question: what happens after the type A/B/C reshuffling of the deck of local churches?

We want to posit four possible scenarios of what happens after that great reshuffling:

Scenario 1 – “Gentle and Winsome”

2s move away from 1s and form thicker bonds with 2.5s and 3s to form a new center of mainstream evangelicalism. In this scenario internal and external critiques of evangelicalism are taken seriously (clergy misconduct, sexual abuse, celebrity culture, corruption, racism, misogyny… etc.) and more culturally conversant, gentler, and dare we say more winsome evangelicalism wins the day. A friend’s report from the recent PCAGA indicated that, in his opinion, this scenario seemed to begin playing out there in opposition to the previous year’s general assembly. As he saw it, it appears many twos have become exhausted with the divisiveness of ones and have begun largely rejecting their polarizing arguments. For this scenario, Type A and type C churches still exist but in smaller numbers and have less sway on their larger institutions.

Scenario 2 – “Nothing Changes”

In short, not much changes. In rural settings we see the highest concentration of type A churches. In suburban and exurban settings type A and type B churches are most prevalent depending on the context and region. In city centers type B and type C churches are most common. This scenario involves a slower rising of tension within denominations as they continue to wrestle with the long-term viability of holding together such contrasting member churches.

Scenario 3 – “Generational Shifts”

We see generational shifts. In the short run, we see type A churches grow in their numbers as baby boomers find more comfort and nostalgia and less political and relational dissonance in these types of churches. This is fueled by the incredible wealth amassed by that baby boomer generation. However, in the mid-term to long run those organizations end up being handed off to younger generations and many see an evolution. In this scenario in the long run type A churches taper off some and type B churches grow somewhat from the type A tapering.

Scenario 4 – “Seismic Shifts”

We see further seismic shifts even larger than 2015-2016 or 2020-2021 that result in an erosion of the middle of evangelicalism into two main groups instead of three. In this scenario. Types A, B, and C churches actually collapse into something different where type B churches fail to exist and collapse into something that looks like only type A and type C because lower 2s keep getting pulled towards 1’s and 0’s and higher 2s keep getting pulled towards 3’s and 4’s.

We are genuinely unsure of which scenarios are most likely. We write from the vantage point of Neo-Evangelicals so we think scenario 1 is most ideal but aren’t sure it is very probable. If you are involved in development work within evangelicalism you know that most of the money in evangelicalism is in the 1.5-2.0 range. There are huge organizations with massive budgets setup in this range. Organizations even just a little to the left of this range have a much harder time raising funds. We think that generational money will be a significant factor in how these scenarios play themselves out.

Will the soul of evangelicalism seek repentance, reform, and renewal or bury its head in the sand?

Will the next word on evangelicalism be renewal and reform or preservation and power?

The jury will be out for awhile.

The generational and monetary inertia probably trends that things remain the same. If this is the case we could see scenario 2 leading to scenario 4 as frustration rises among the high 2s with the lower 2s and high 1s who are more resistant to substantive reforms. However, recent pointers from the SBC annual gathering (reception of the task force report, rejection of CBN candidates, etc.) and the PCAGA (mentioned above) seem to indicate the door to scenario 1 remaining open. What is at stake is the shape and soul of evangelicalism in the middle of the 21st century.

Our deepest desire is for an evangelical faith that promotes orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopathos. We believe that the 2.5 to 3.5 range has the best balance of these priorities, commitments, and values. We are not naive. We know that this group is probably the smallest and least influential within evangelicalism. We know that it is not well-funded. We know that not many institutions have set themselves up in this range. Without drama, anxiety, celebrity, or pomp we commend a quiet, sincere, humble, local, beautiful, and non-anxious way forward.

Reflections on the Broader Culture

Political vs. Theological Evangelicals and the Evolution of Self-Identification

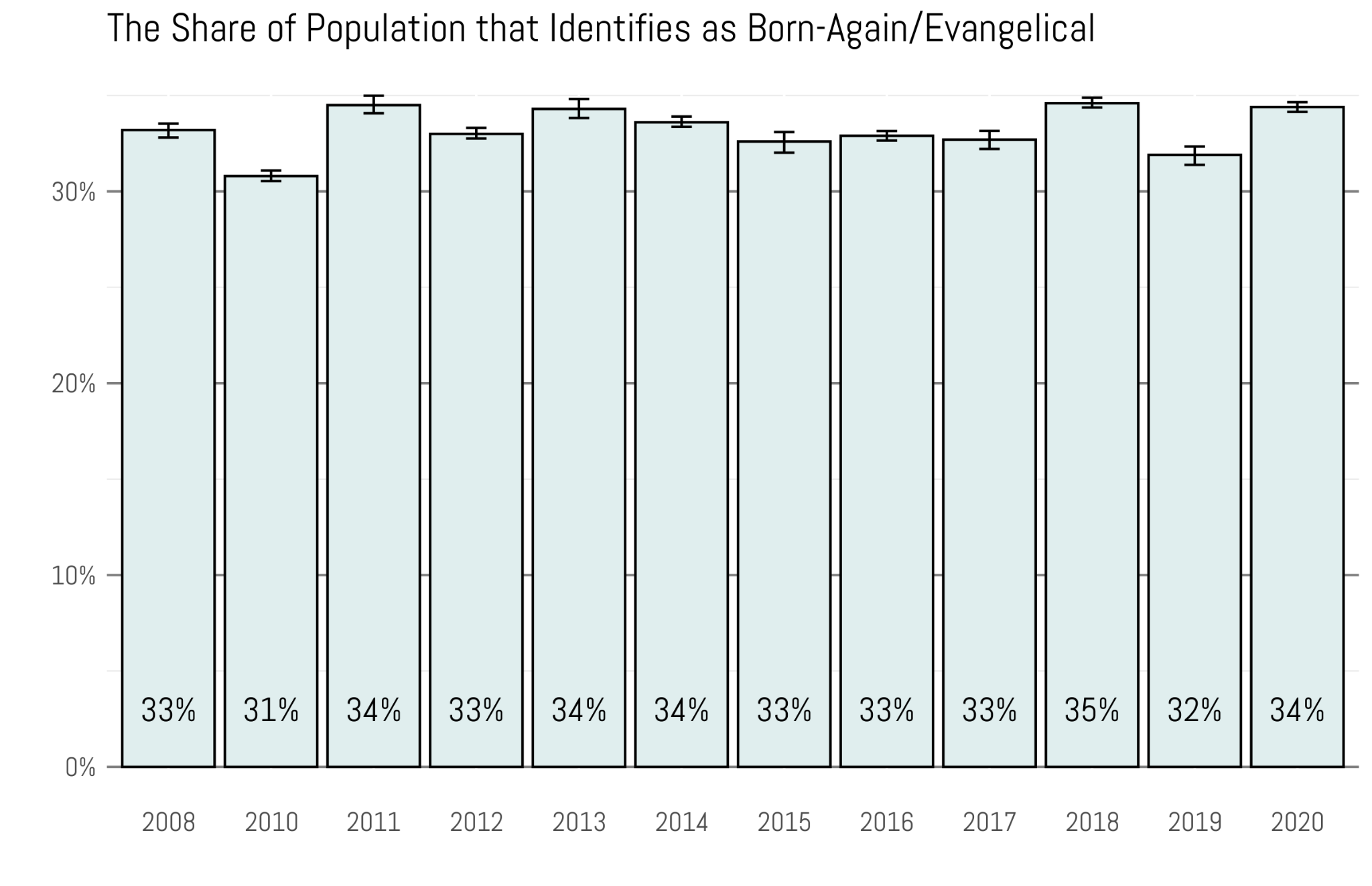

Despite the massive rise in dechurching, deconstruction, and other off-ramps from evangelicalism, the number of self-identified evangelicals in America remains the same. The reason why is not surprising, if you have followed the last several years of political happenings. There is an increasingly clear picture here showing the rise of political evangelicals as opposed to theological evangelicals. The most plausible explanation for why we still have the same number of self-identifying evangelicals today even as tens of millions of people have left evangelicalism is that millions of new political evangelicals now self-identify as “evangelical” in the polling data.

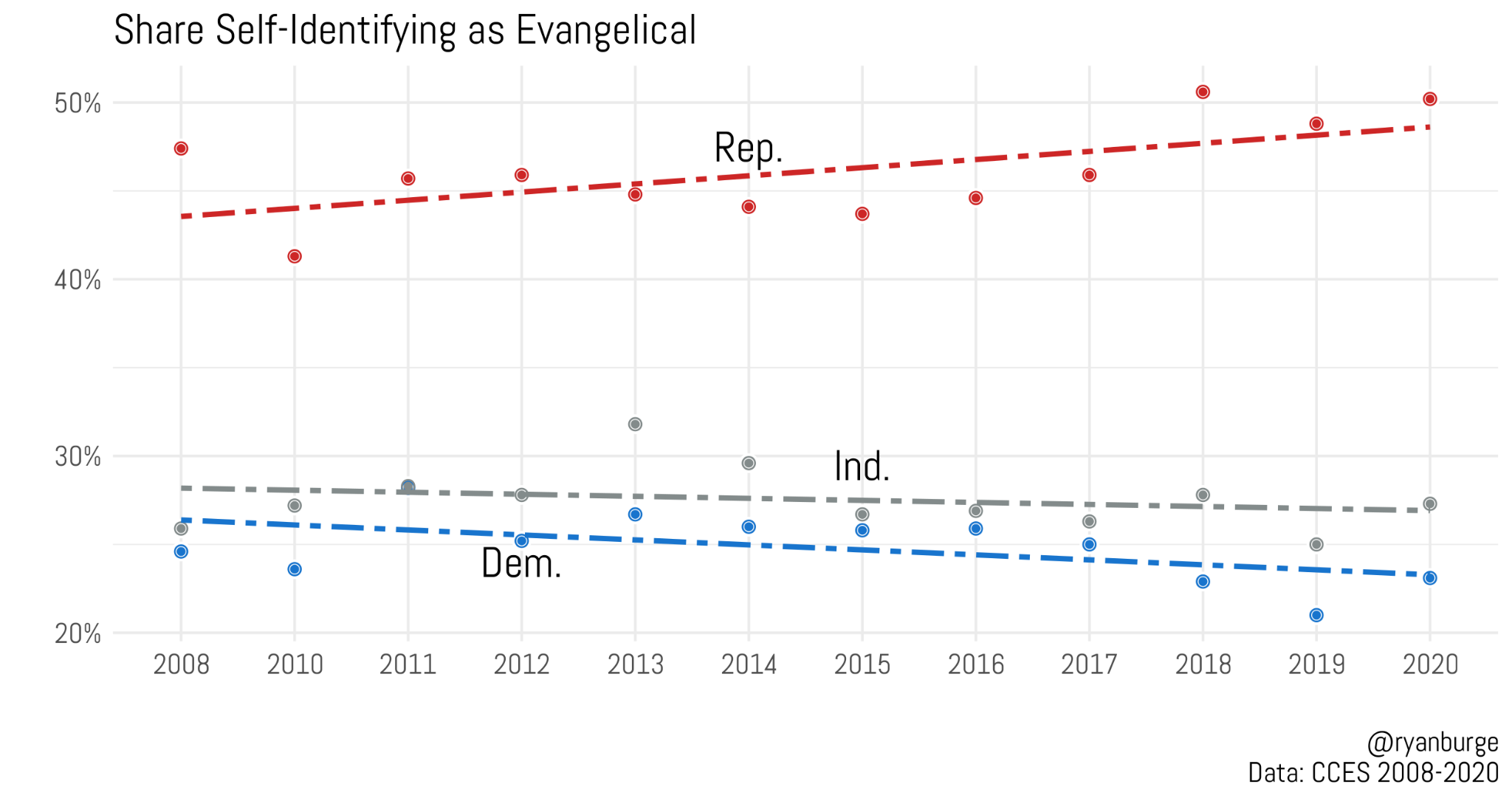

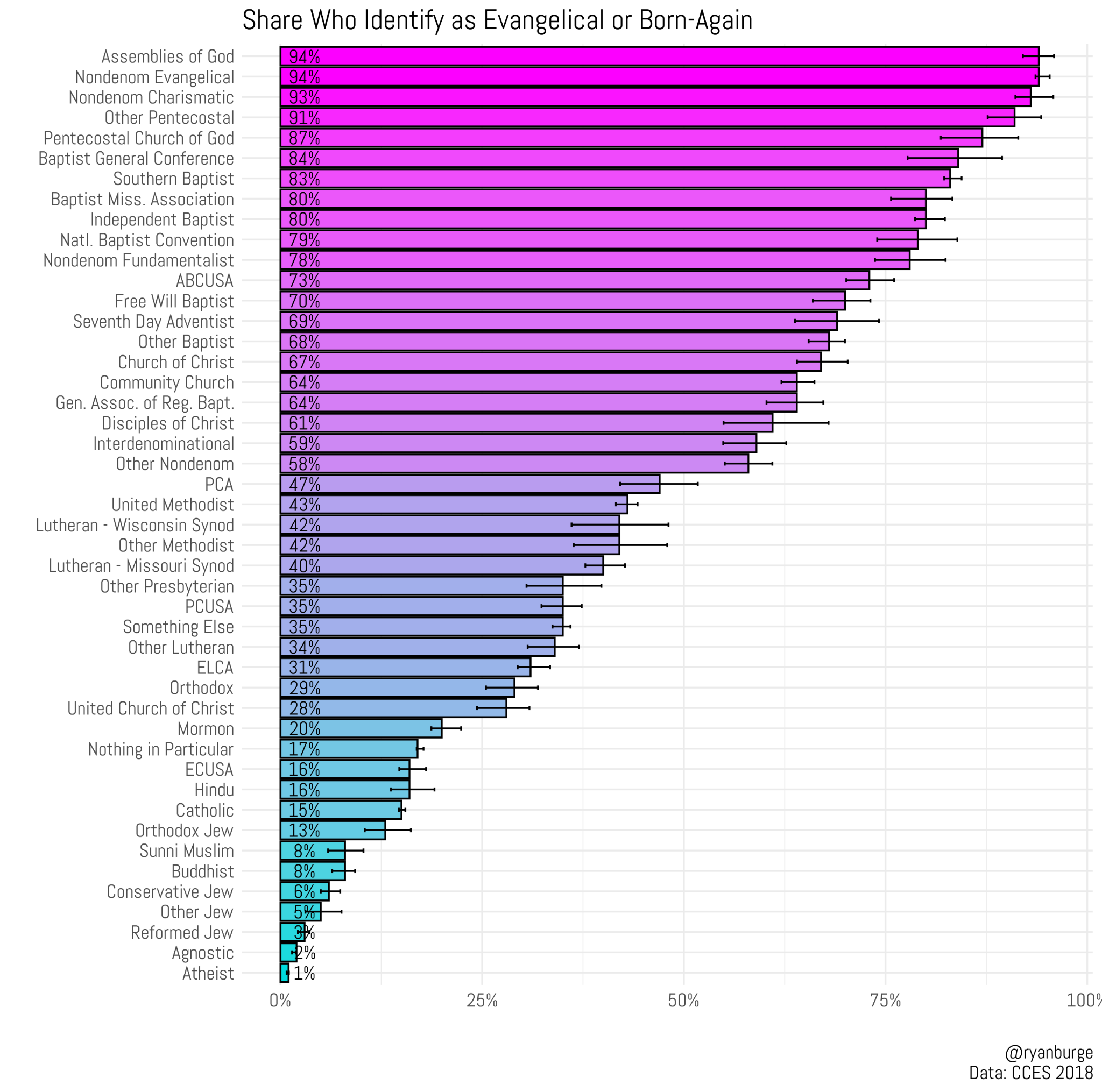

Consider the following graphs from sociologist Ryan Burge that explore the evolving landscape of self-identified “evangelicals.” In this first two graphs we see increasing partisanship over time:

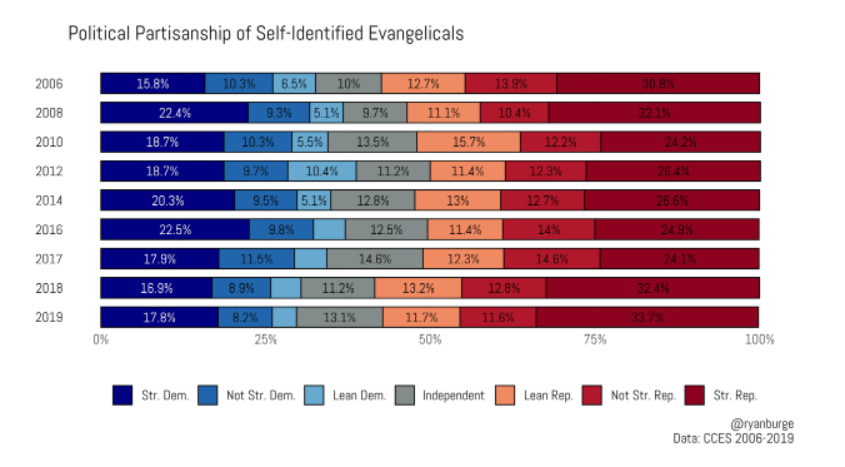

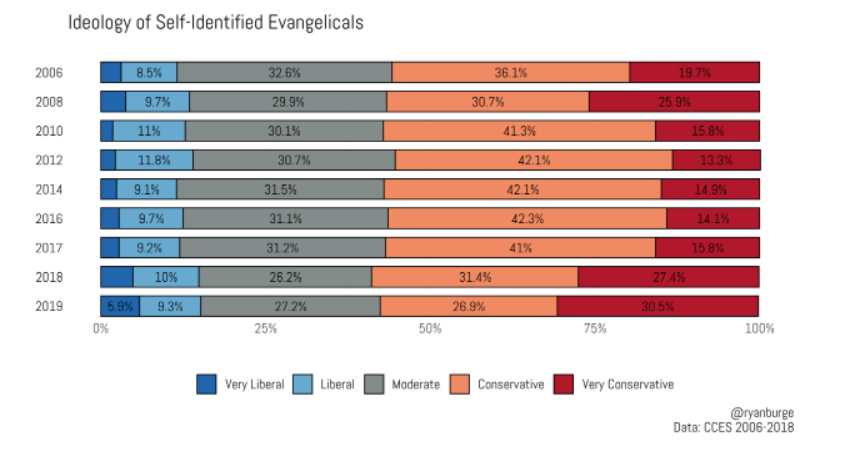

Further, we see that ideology among self-identified evangelicals has become even more polarized relative to partisan identity:

Further, we see that ideology among self-identified evangelicals has become even more polarized relative to partisan identity:

The evidence suggests that many who lack even basic Christian commitments are increasingly identifying as evangelicals, along with party allegiance to the Republican party. When you drill down on those who identify as “evangelical” or “born again” things get even weirder. We see that 29% of Orthodox Christians (roughly 1.7M people), 20% of Mormons (3.4M people), 15% of Catholics (10.6M people), 16% of Hindus (0.4M people), 13% of Orthodox Jews (0.5M people), and 8% of Sunni Muslims (0.2M people) self-identify as evangelical or born again.

This isn’t even a comprehensive list of non-theological evangelicals who self-identify as evangelicals or born again and this group of people is 16.8M people and is alone 16% larger than the Southern Baptist Convention (14.5M members) which is the nation’s largest evangelical denomination.

Information Consumption

The political reshuffling continues to play out from the fracturing of evangelicalism, and while small implications of it might play out in 2022, the trajectory will likely not be more fully understood until the next presidential cycle. With the Supreme Court deciding the future of abortion laws leading up to the 2022 cycle, it will likely mean that a wide range of the evangelical camp will hold together in their voting. The lack of Trump’s presence directly on the ballot will go a long way in this regard. Projecting to 2024 is more difficult with the primary actors remaining to be seen.

In the meantime, the largest implication that has come to the forefront after a year of reflection is actually the one we listed last in our discussion of what the fracturing could mean for broader culture: information consumption. This one factor will largely shape the future of evangelicalism on the national, political, personal, and ecclesial level.

The information consumed for groups 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, and 4+ are vastly different even in the ways they respond to the same set of events. Simply searching for one event that is heavily covered and reading the headlines will reveal the ways information is being used to shape opinions under the guise of a mere reporting of the facts.

The information consumed by groups 1-2 will largely tend towards deep distrust of the sources the other groups rely on. They will claim secret agendas, suppression of truth, antagonism to Christianity, and liberal bias from any other source. Their sources of information are becoming increasingly decentralized, taking the form of internet blogs, podcasts, and individual personalities.

On the other side of the spectrum, the sources relied on by the 4+ groups, and some of the 3-4 group, will repudiate the information coming from the 1-2 group for similar reasons: secret agendas, distortion of the facts, preservation of power by white males, and conservative bias. Their sources continue to be structurally supported by big named media companies, with other sources like Twitter and TikTok playing an increasing role.

The middle groups do not then find their own middle of the road news sources but are often left picking and choosing from the various resources offered above.

Overall, if the old adage seems less than true when considering our diets, it has certainly proved true concerning our information diets. We are what we eat. Though the extremism that defines much of information media today does not seem to match the reality on the ground, increasingly it will not be surprising to see folks repeat the talking points they hear and be shaped by their underlying beliefs.

Christianity will have to wrestle with this challenge moving forward. The power of God’s word has a shaping power that far exceeds the power of secular messages, but the amount of time spent with secular messages overwhelming exceeds the amount of time the average Christian spends in the word – personally, communally, or ecclessialy.

Reflections on Hope

The hope we held on to a year ago remains firm and is even stronger than it was before. The digital realm can be dominated by those on either extreme. At times, it feels as if the deeper you engage in the online discourse concerning the future of the church the more discouraged you feel.

But over the course of this year we’ve had countless opportunities to talk through the content of the original Six-Way Fracturing article. The main reaction we had to it was people expressing gratitude for giving some language and framework to hang their real life observations in their own context. Through these conversations, we have been able to see even more powerfully the hope that many pastors, leaders, and churches see on the horizon. Many of these folks were the same who a year ago we encountered as beaten down and discouraged. We both now have close friendships from other people who have a deep desire for building healthier churches, ministries, and institutions.

It is in them that we see the future of evangelicalism and the answer to the question, “what do we do now?”

The largest unmet concern we see is a lack of critical mass of persons, money, and institutions that refuse to be culturally captive in any direction. People need to bring repentance, reform, and renewal to existing institutions as well as gather and form new healthy institutions. That repentance, reform, and renewal simply looks like the application of all of Scripture and all of general revelation to all of life. That’s a daunting task but it isn’t that complicated if we think about it: sound doctrine + Biblical ethics + healthy affect in embodied individuals, organizations, and institutions. For renewal to be had in America or the West we will need consistency on these things. We will need non-anxious leaders (see Friedman’s A Failure of Nerve and Sayers’ A Non-Anxious Presence here) who aren’t afraid to be in a perpetual three-front war of the secular left, the secular right, and the world/flesh/devil. Tim Keller has given numerous actionable ideas both in his short (and free) How to Reach the West Again as well as several other ideas in his episode on the Mere Fidelity podcast entitled, “Saving Evangelicalism.”

Those that embrace the uncomfortable middle range will need to rely on telling better stories than the polarities to grow. This is true for both winning hearts and minds as well as for the pragmatic reason that partner development is difficult when you employ a prophetic voice, especially when that prophetic voice is directed in several different directions and axes. There will need to be significant developments theologically, practically, and organizationally fleshing out ethical and affective aspects of our faith. There are numerous underexplored areas of the faith including the imago dei, aesthetics, mental health, and a wide swath of current and future ethical issues (gender/sexual/reproductive ethics, web3, transhumanism, economic matters, racism, misogyny, abuse… etc.). Pastors will need to patiently pastor their flocks and exercise tremendous wisdom on how, what, when, and where to apply some fine grit sandpaper. Sometimes even the 220 grit will get you fired, sadly we’ve seen this many times over the past few years – we see you and we care.

If we wish to see our people grow we must challenge and change how they are being formed. Pastors simply can’t compete with the sheer volume and depth of ways that their congregants are being formed throughout the week. Spiritual formation must evolve to actually get upstream from people’s information consumption and actually change the constellation of voices, resources, and institutions forming their hearts, minds, and wills. Without new information consumption people will not change.

Our Gospel is true, good, and beautiful. We will be in serious trouble in the middle of this century if we only have a Gospel that is merely true. We must recover the good and beautiful aspects of our faith drawing both from God’s Word, the great cloud of witnesses we have from church history, and at all times and in everywhere relying on our Triune God. To him be the glory forever.

Topics: