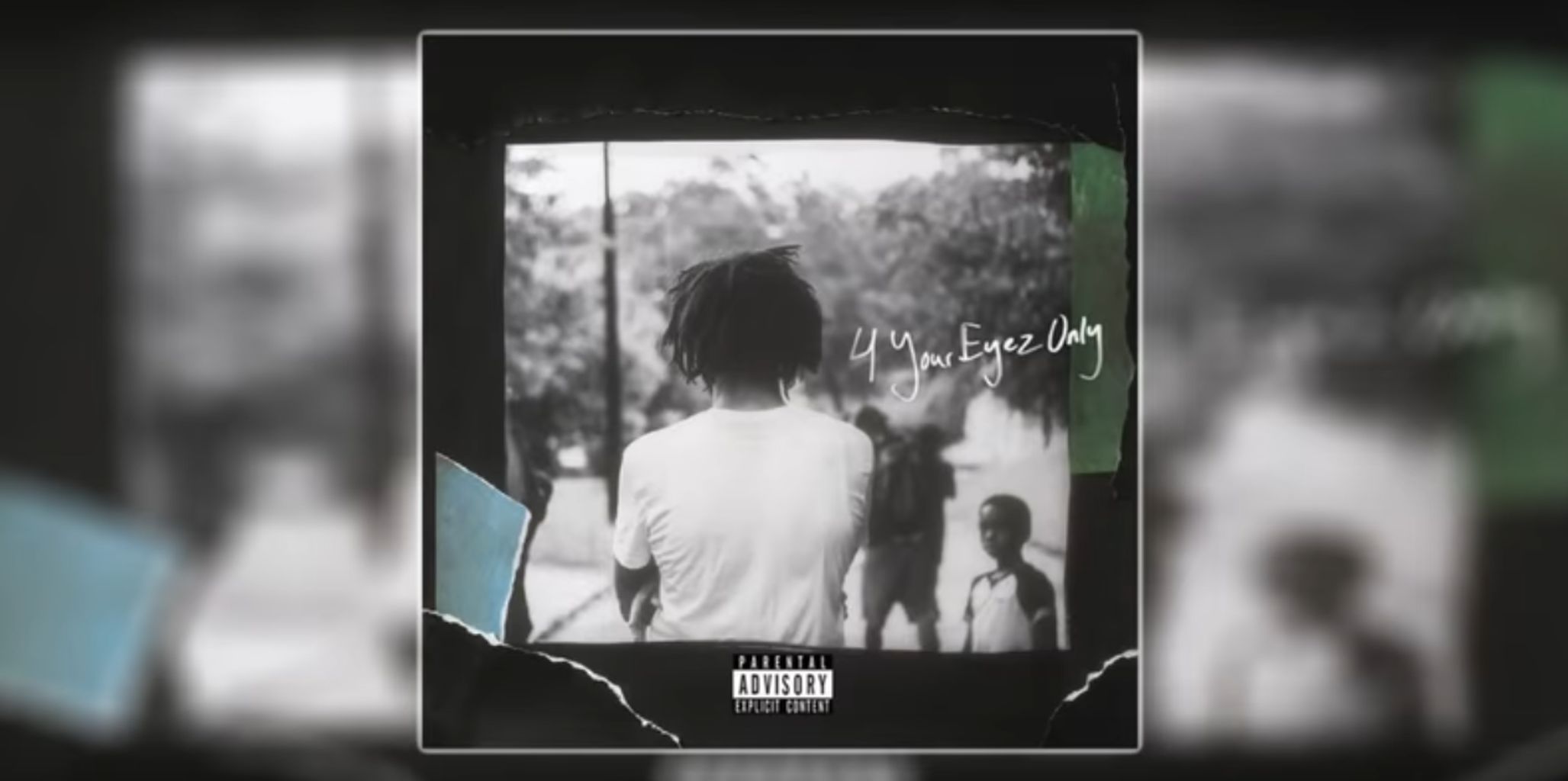

In my lessons on Christianity and social justice, I always feature clips from J. Cole’s 2017 HBO documentary For Your Eyez Only. The film, directed by Cole and Scott Lazer, features interviews with residents of small black cities throughout the South and Midwest, and intersperses songs from his album with the same title. Though Cole may have an ambivalent relationship with organized Christianity, his film offers a vision of an authentically Christian approach to social justice. And although it was released 3 years ago, it comes as a breath of fresh air today as we approach the 2020 election season. Cole reminds us that true political change isn’t only in the hands of the person in the White House. Rather, it begins on the most basic level possible: in the heart, the home, and the local community.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: