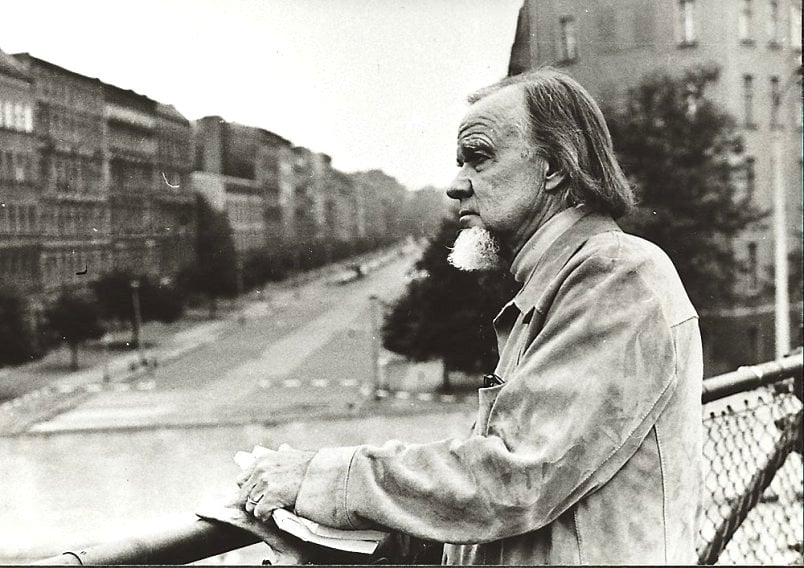

I am delighted to be able to publish this guest feature from Dr. William Edgar of Westminster Theological Seminary. Dr. Edgar is the author of Francis Schaeffer on the Christian Life: Countercultural Spirituality published by Crossway.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: