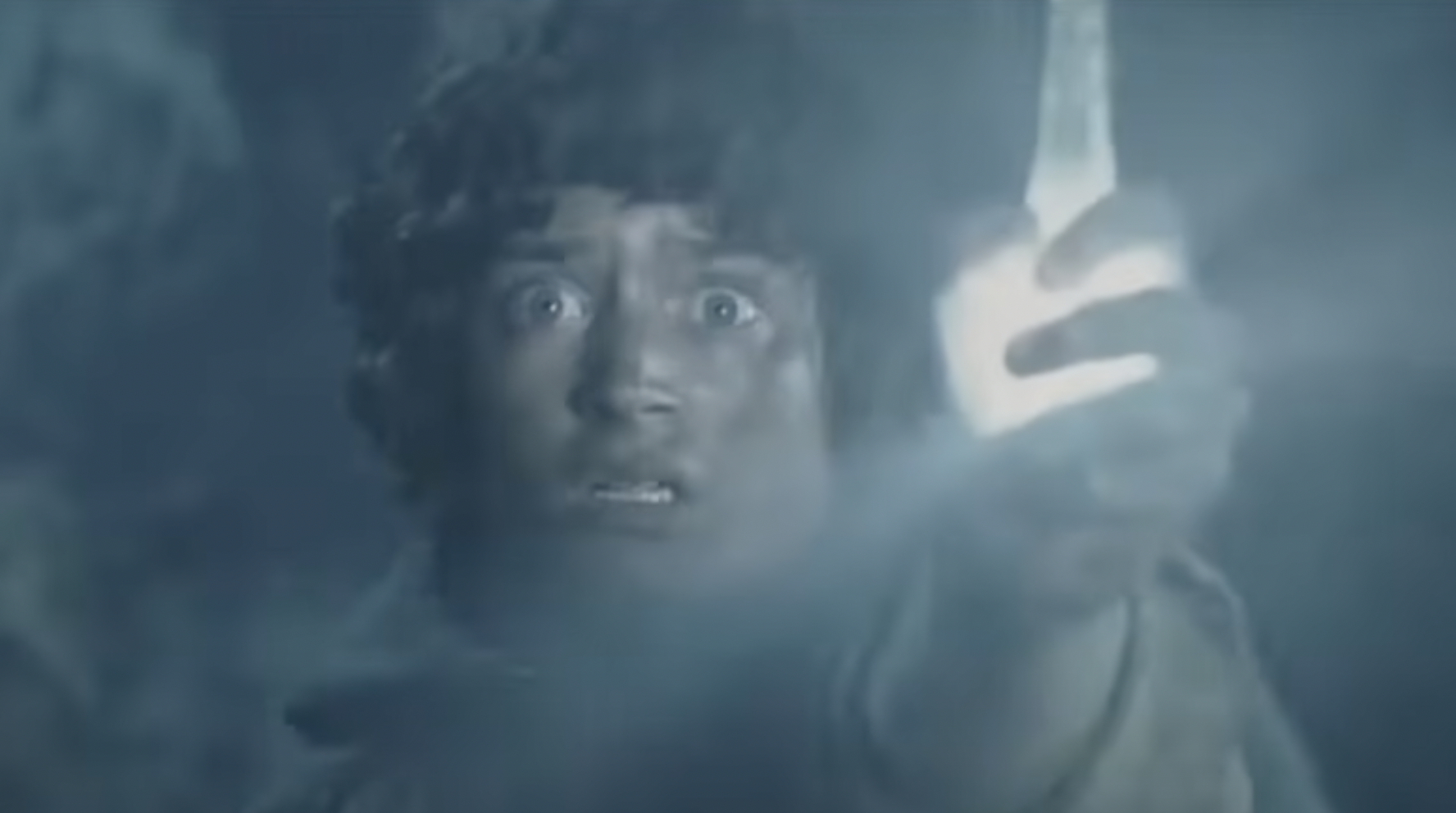

The whole of the Christian life is lived in a time of Advent-like expectation for the coming of the Bridegroom. Far from a passive, sedentary waiting room, the anticipation that structures the whole of Christian existence is far more dramatic and perilous. It is more akin to the expectation of someone adrift at sea who scans the horizon for aid, or an embattled and outnumbered group of soldiers who desperately hope for the arrival of support. Simultaneously, as the poet Christina Rossetti captured in her “Advent Sunday,” the expectation of the Christian life is a yearning not only for the unveiling of the triumphant Savior King, but also the Bridegroom our souls desire to rejoice with.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: