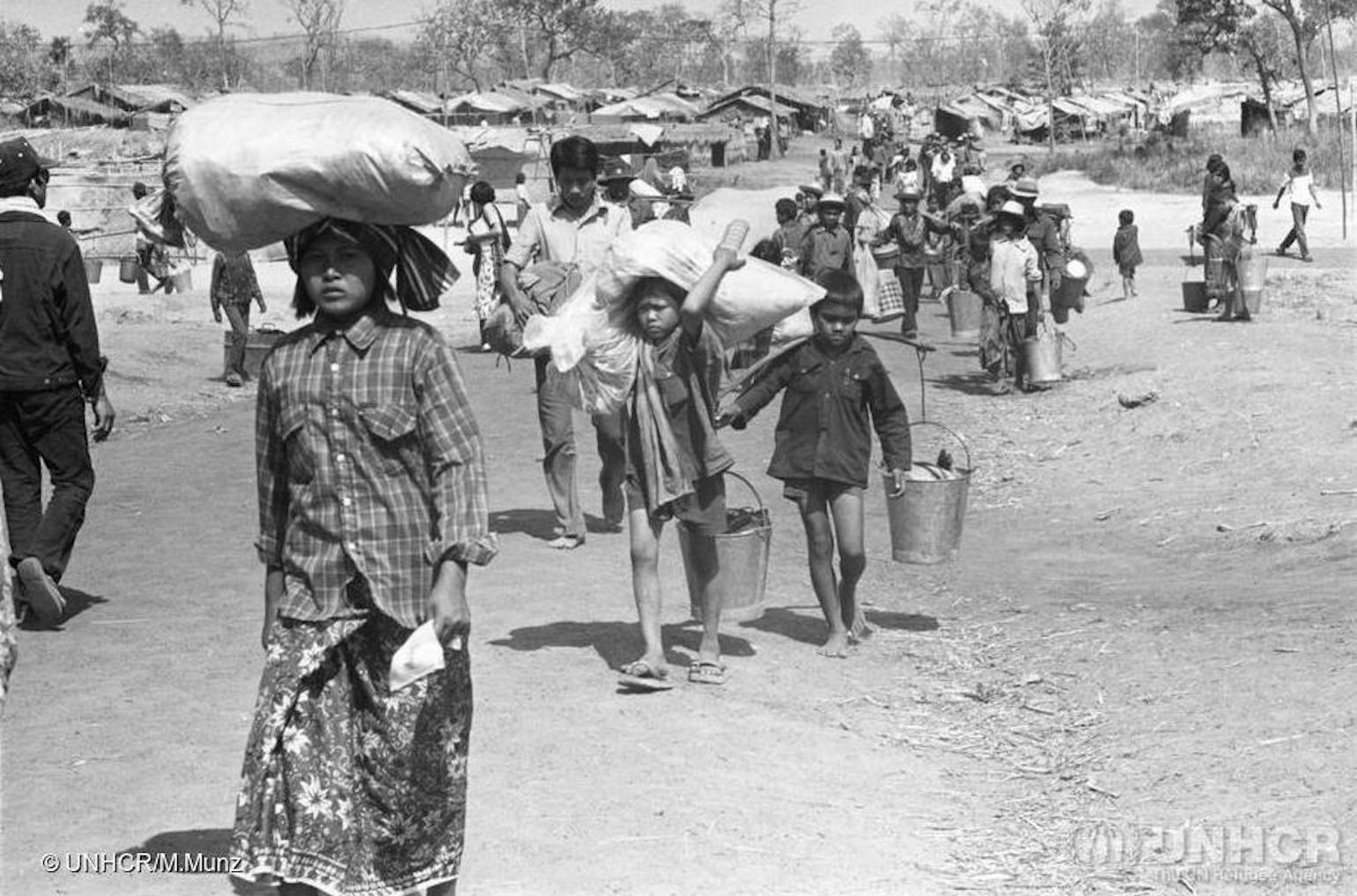

The year our son turned two, a Cambodian family moved in upstairs. They came off the plane that had brought them from Thailand, each carrying one paper shopping bag, the husband and father holding a very small boy by the hand. They spoke enough English that the group from our church who met them could shepherd them out of the Philadelphia airport into the van that awaited them. On the way to the van, the welcoming committee passed the baggage claim, assuming there was more luggage to pick up. But the family made it clear that what they owned was in the bags; there was nothing else.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: