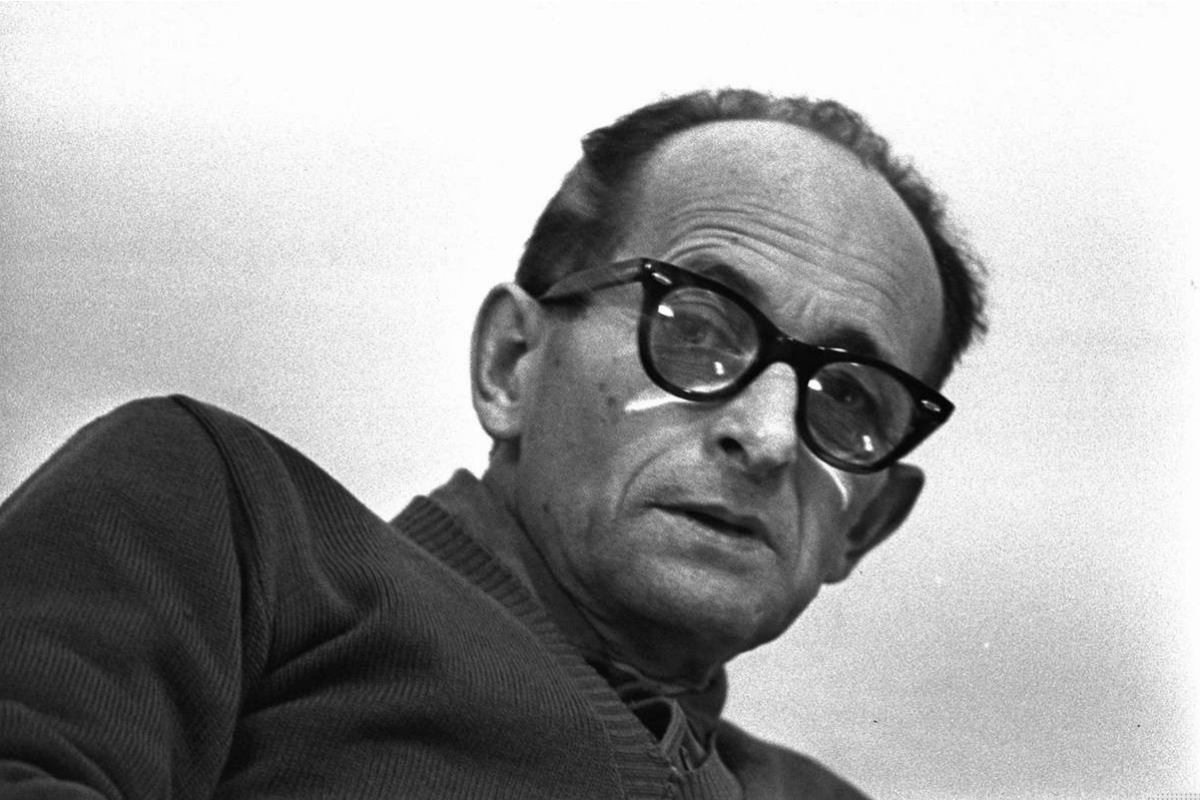

A middle-aged man sits in a glass booth, or perhaps a cage. He seems bewildered, surprised to be there. His nervousness is visibly manifest to all onlookers—the trembling mouth, the shocked near-sighted eyes, the hands nervously clutching each other for comfort.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: