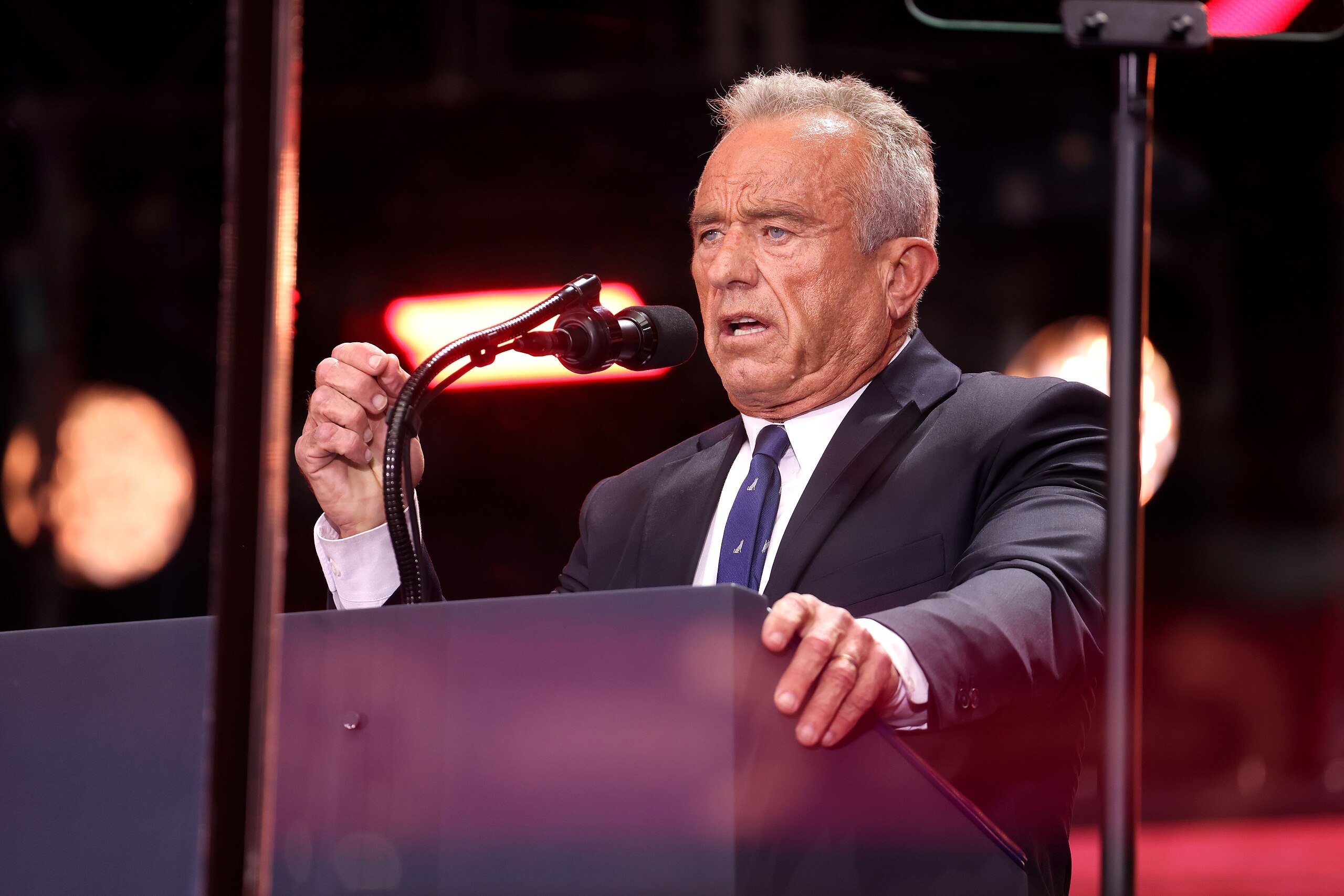

The Make America Healthy Again movement (MAHA) wants Americans to be concerned about medicalization. The MAHA report released earlier this year specifically focuses on the overmedicalization of children, but it’s clear from their communications and other statements by HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. that medicalization is a problem for all Americans. The report describes quite accurately that pharmaceutical companies have undue influence on medical providers, particularly when it comes to prescribing drugs for children: “The distortion and influence of medical education, medical knowledge, and therefore clinical guidelines and practice, has led providers to over-diagnose and over-prescribe, and over-use by children, while largely ignoring the potential population-level impact of diet, lifestyle, and environment as focal points for health, healing, and wellness.” While their sentence construction could use a little smoothing out, the research they marshal to make their point absolutely supports their conclusion: for decades, pharmaceutical companies have used slick advertising and massive piles of cash to influence how healthcare providers write prescriptions. In America, this has led to rates of prescription for drugs like amphetamines for ADHD that dwarf comparable developed nations.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: