I’m pleased to publish this guest post from Dr. Matthew Emerson.

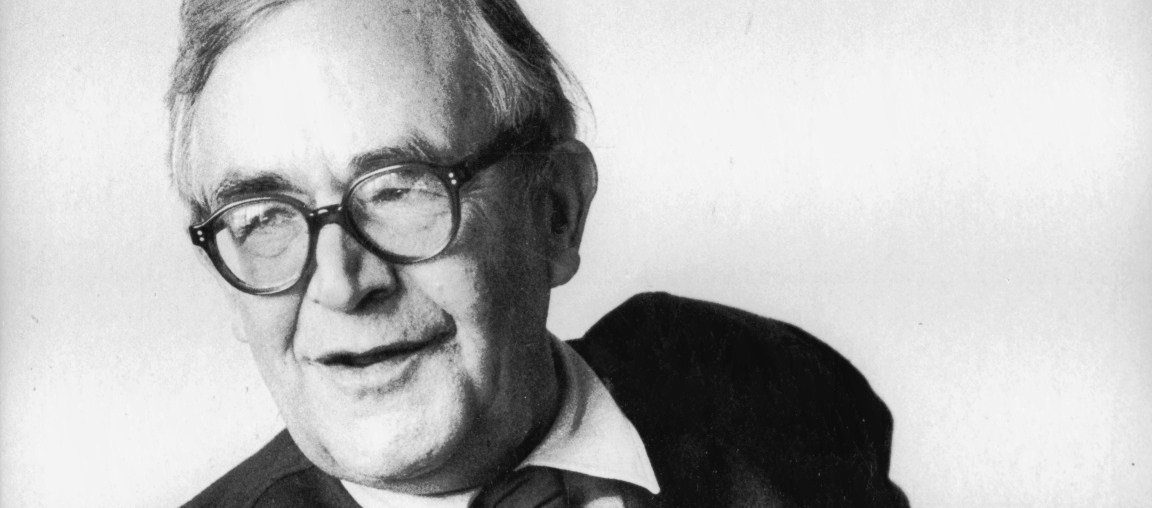

Recently, Christiane Tietz’ Theology Today article, “Karl Barth and Charlotte von Kirschbaum,” was a hot topic in one small corner of the internet, occupied mostly by academic theologians. Tietz’ essay contains the first English translation and publication of letters written by and to Barth, Kirschbaum (his secretary), Nelly Barth (his wife), and Barth’s mother, all of which speak to in some way the relationship between Barth, von Kirschbaum, and Barth’s wife.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: