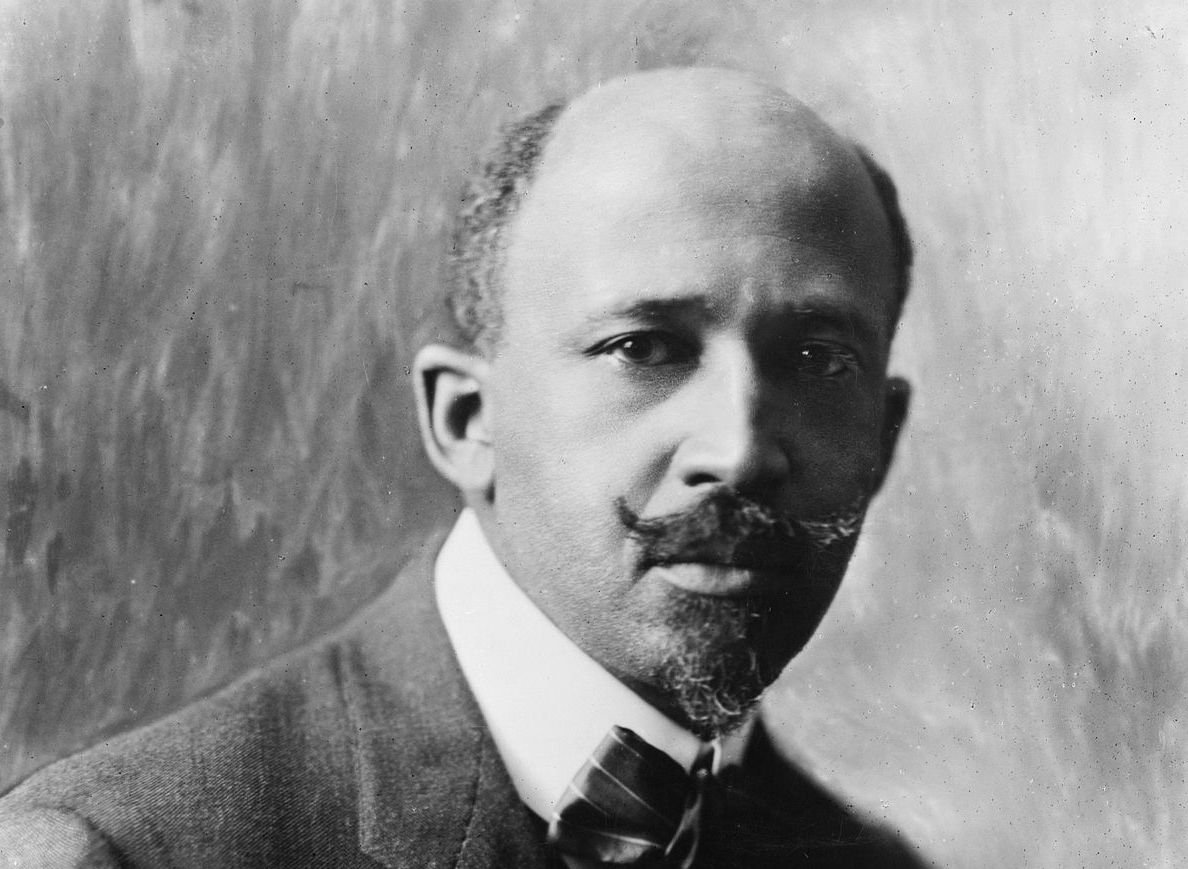

In chapter four Du Bois reflects on his time teaching at a black one-room schoolhouse in rural Tennessee. As such, most of the chapter is simply taken up with recounting what life looked like for an itinerant black school teacher in rural Tennessee in the late 19th century:

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: