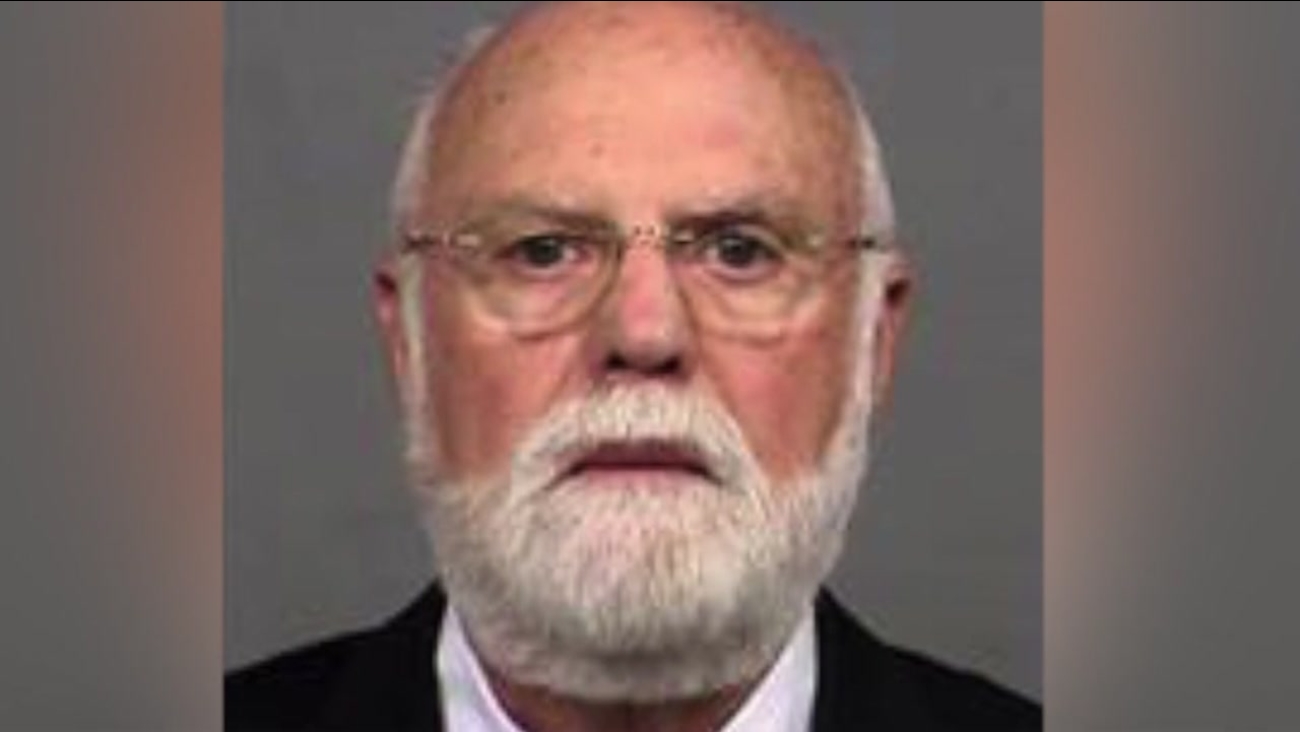

Last week’s essay from Matthew Lee Anderson and Andrew Walker about evangelicals and in vitro fertilization makes an argument worth discussing: God intends that sex and procreation should not be separated from each other. It made me think of the story of Donald Cline, the fertility doctor who (unknown to his patients) used his own sperm when inseminating his patients, eventually “fathering” at least 50 children.

The Atlantic article about Donald Cline by Sarah Zhang on Cline is well-told, but with Cline and his lawyers refusing to comment, the best conclusion that can be drawn about Cline’s motivation is this: he did it because he wanted the best results. He wanted to be the best, and he didn’t want to let his patients down. He mastered the technique of using the freshest sperm—and then he lied to them about how he did it.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: