I held out for as long as I could. My resistance was sustained chiefly by a stubborn contrarianism that resists as many trends as possible, particularly those that can be credibly connected to New York City, Washington, San Francisco, or Los Angeles.

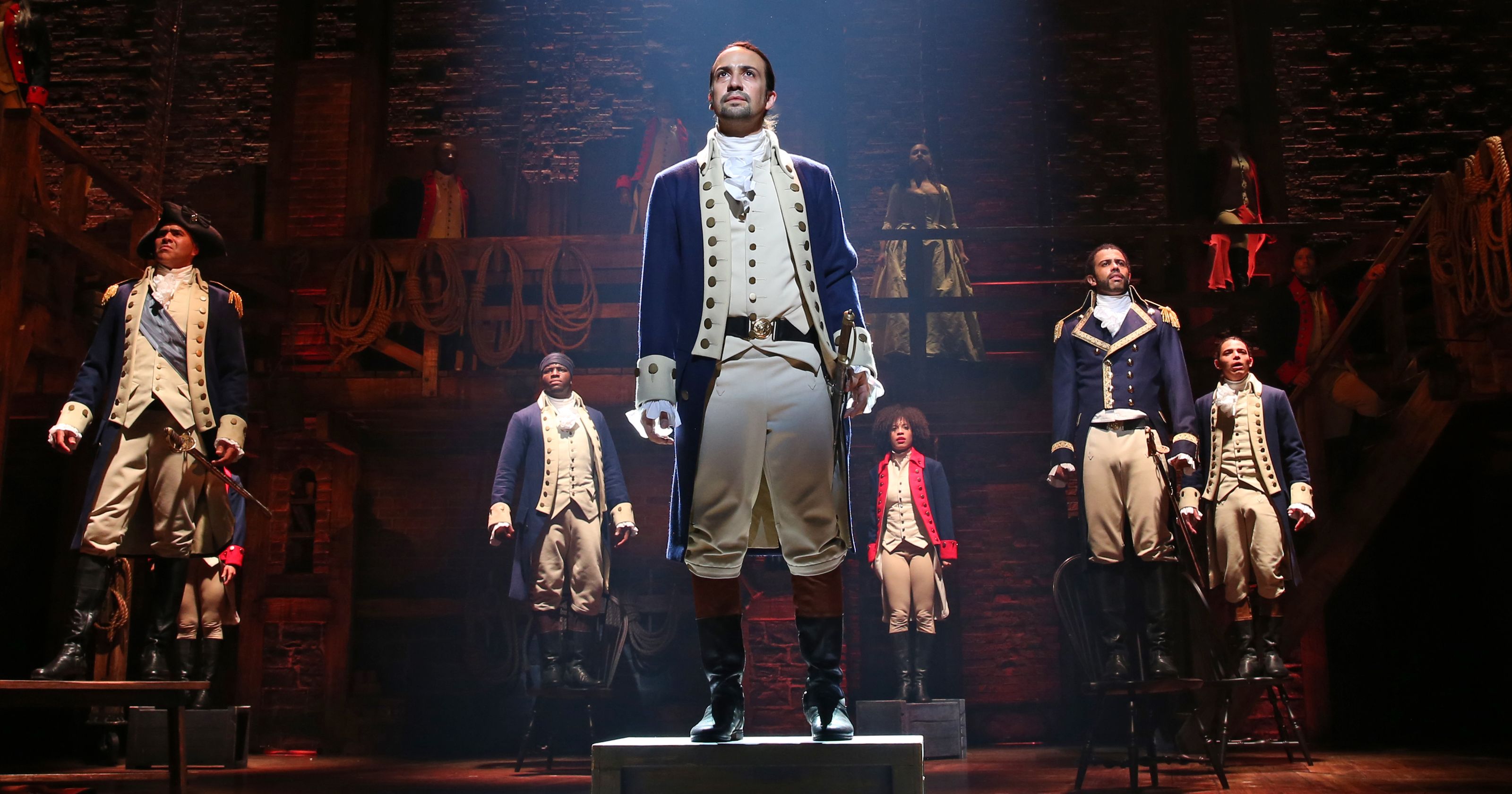

But in the end I succumbed: I’m now a Hamilton fan.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: