By Joshua Heavin

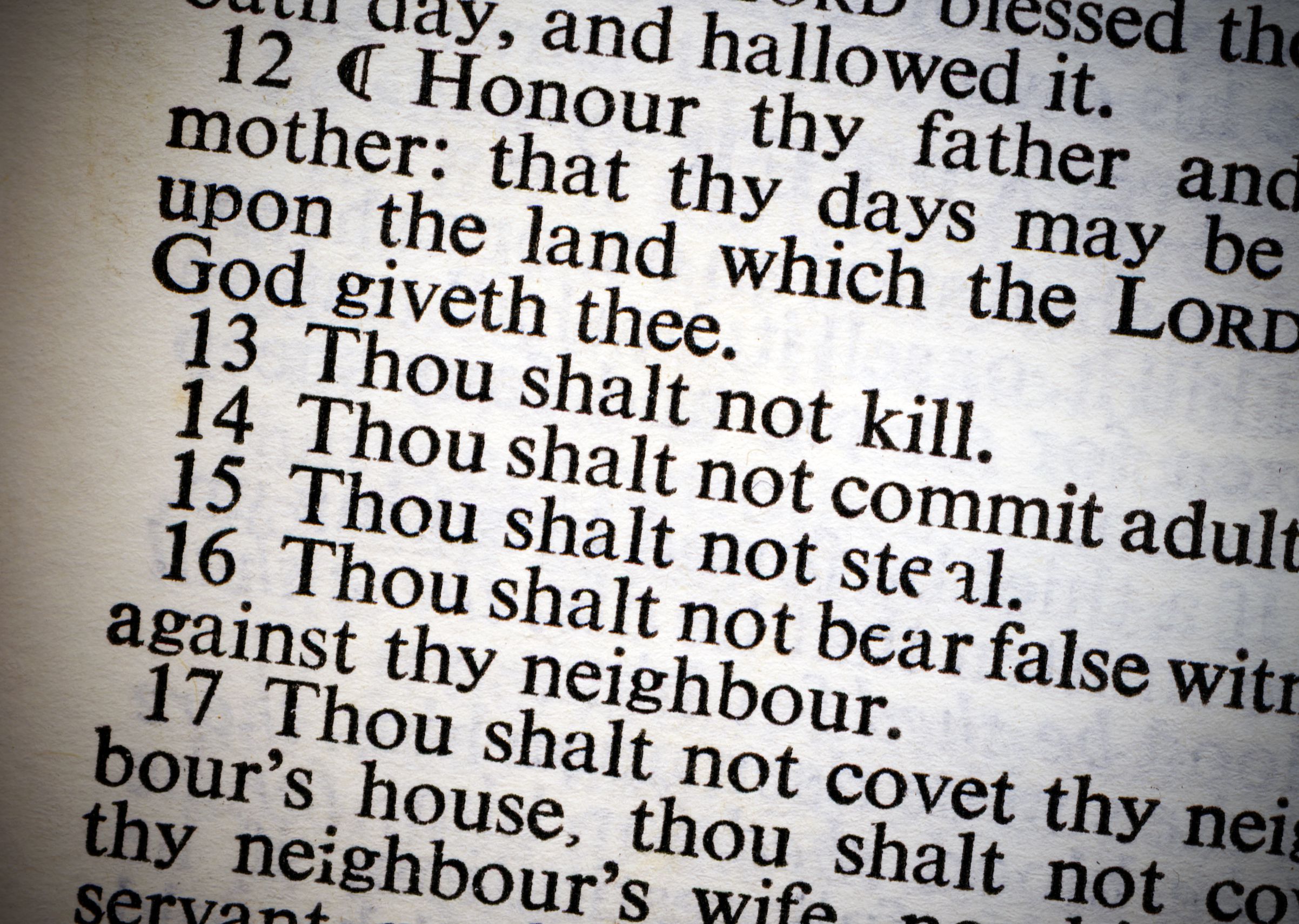

Collin Hansen recently tweeted, “I’ve come to expect that many will lie about what I say and think. It’s part of the job for me and life for all of us in this fallen world. I don’t quite know what to make of the fact that almost all of the lying comes from professing Christians who know the truth.”

Hansen’s lament is probably applicable across the political and ecclesial spectrum. What makes that uniquely tragic is that Christians have a particular duty to accurately represent our interlocutors.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: