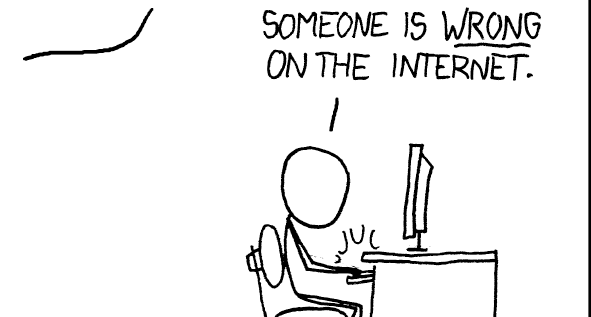

Here’s one of the the under-discussed realities behind the infighting and controversies we see in churches, denominations, and networks today: we’ve yet to learn how to coexist and do ministry together in a digital age.

Just start at the local level. One reason there may be disunity in a local congregation is church members are together in person less and yet visible to each other online more. Facebook comments, threads on X, and Instagram posts introduce us to a greater number of our fellow congregants’ perspectives and outlooks than in the past. Over time, it’s inevitable we may wind up surprised that they stream that show, or support that politician, or frequent that restaurant, or recommend that author, or oppose that law, etc.

Zoom out to networks and denominations, and you see the same challenges at work. We are together in person less, but open to each other online more.

What if the problem isn't too little visibility, but too much?

When I consider why uneasiness, concerns, and quarrels have been on the rise in multiple denominations and traditions—whenever I talk with leaders across the spectrum about the issues they’re debating—I can’t help but wonder if, in many cases, the issue isn’t a lack of visibility into church life but rather overexposure.

Simply put, we can see into each other’s churches more than ever before.

In an age where every church has an online presence, where pastors and staff can offer hot takes on whatever is happening in the world or in DC, where the majority of churches livestream their services, we have an unprecedented ability to observe what’s happening in congregations far beyond our own. And while we might be inclined at first to assume this development is positive—greater transparency, greater visibility, greater openness—research suggests it may actually be counterproductive to long-lasting partnerships.

Proximity breeds contempt.

Nicholas Carr’s new book, Superbloom, devotes a short chapter to antipathies in the digital era. He cites a study from the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology that found proximity in a physical neighborhood to be a key factor in disliking other people—more so than in liking them.

The closer your proximity to someone, the more likely you will get irritated at some point by their mannerisms, their habits, or their opinions. The old saying that “fences make good neighbors” holds up, because the more visible someone is to you, the clearer their foibles come into view. And once you notice something irritating, you can’t unsee it. Their quirks, their comments, their way of doing things—minor annoyances can turn into full-blown frustrations. Proximity keeps those irritations always in view, which can lead to resentment, then antipathy, then a cycle of enmity.

Church history is replete with stories of this happening in the physical world. Just one will suffice. Consider the official unity among certain Eastern and Western churches until migration patterns brought their distinctive worship practices into closer proximity. Suddenly, church leaders were debating the proper way to make the sign of the cross (three fingers, left to right, or two fingers, right to left?) and Christians were aghast at their fellow Christians’ use of leavened (or unleavened) bread in the Eucharist. They were united… when they were distant to each other. Proximity led to fracturing.

Now watch how Carr applies this insight of proximity leading to contempt in the digital age:

“Now that we’re all virtual neighbors, we’re all in one another’s business all the time. We’re exposed, routinely, to the opinions and habits of far more people, both acquaintances and strangers, than ever before. With an almost microscopic view of what everybody else is saying and doing—the screen turns us all into Peeping Toms—we have no end of opportunities to take offense.”

It’s natural, Carr writes, to be biased toward people who share similarities with us and to dislike people who are different. But here’s what the research shows: something we dislike about someone else carries far more weight than all the things we might appreciate.

“As all this personal information swirls around the net, people find a lot of evidence of what they have in common with others and a lot of evidence of what they don’t. They see likenesses, and they see differences—and over time… they begin to place more weight on the differences.”

There’s a snowball effect here. And when you apply this insight to denominations, networks, and church families, you see just how much of a challenge this presents for long-term partnership.

How This Plays Out in Denominations

The internet has enabled church networks to become a giant observation deck. We’re all familiar with the “virtual stalking” that’s commonplace when you scour social media sites, looking up someone you've just met. The same possibility presents itself when pastors and church members freely and routinely browse other churches online. We peek in on how they worship, how they pray, how they preach, or how they administer the sacraments. And thanks to social media, anyone can launch an accusation, issue a critique, or voice a concern about anything they feel is out of step in a sister church.

A pastor says something off in a sermon? Clip it and share it—it may serve to discredit the pastor or serve as a warning for others. A staff member posts something politically loaded? Screenshot it and circulate it—it’s evidence of right-wing fanaticism or left-wing wokeness. A pastor gives counsel or instruction that makes sense for their local context? Doesn’t matter—it can be dissected and judged by Christians a thousand miles away who know nothing about that particular congregation or its needs.

Confessional alignment doesn’t fix this problem. Even differences in how a church adheres to and applies her confession can come under scrutiny. If Carr’s research is right, then the moment you notice a sister church does something different than yours—different enough to be irritating, offensive, or concerning—that’s what sticks in your mind. You’re more likely to dwell on or exaggerate the snowballing set of differences than to celebrate the similarities that were the foundation of your partnership in the first place.

Sometimes the disagreements involve matters of political prudence, not theological consistency. How strange to see some churches gravitate toward partnerships formed around political instincts or political posture, yet with little to no doctrinal agreement at all. It’s not uncommon to see a pastor gladly lock arms with others who disagree on baptism, church polity, the nature of salvation, and a whole host of theological matters, while brandishing torches and pitchforks toward a fellow pastor who holds to the same confession of faith and belongs to the same denominational family but just reads the political landscape differently.

The Incentive to Stir Controversy

Denominations have yet to figure out how to navigate this new reality. The incentives push us toward fracture, not wholeness. Grandstanding, not caution. The current online environment often rewards pastors with little involvement in their local association of churches—who contribute next to nothing to denominational causes, yet can build influence simply by “exposing” what they dislike in other churches or creating a narrative (often a false one) that’s convenient for whatever cause they want to push.

Imagine this scenario, one admittedly farfetched: A worship leader in a livestreamed service prays in a way that unintentionally veers into patripassianism, wrongly attributing the Son’s work to the Father—“Father, thank you for dying on the cross for our sins.”

Now imagine someone in another state, scouring livestreams, VBS literature, church websites—mining for similar misstatements. He collects clips, screenshots, and sermon excerpts, dripping them one by one online to build a case: This denomination is drifting from its Trinitarian convictions! The narrative gains traction. Alarm bells go off. Look at all these examples of heterodoxy! Suddenly, this is the conversation everywhere. People start hunting for more examples to confirm the crisis, fueling a movement to counter the supposed theological slide.

Of course, the reality is much more mundane. In every era and every place throughout church history, you find a measure of theological sloppiness. Unfortunate, yet also unavoidable. Even the most careful preachers have moments of imprecision. A poorly worded prayer, a clumsy sermon analogy, a faulty conclusion—none of it signals a coordinated departure from orthodoxy. But in the online outrage economy, mundane doesn’t sell. The most dramatic interpretation wins. And the evidence accumulates and gets stored up online, waiting for someone to exploit the examples and connect dots somehow so as to create or confirm a narrative.

The above example is exaggerated, yes, but I’ve seen similar movements unfold across multiple denominations over all kinds of issues. We’re going to have to start resisting the impulse to believe every breathless narrative that circulates online. And church leaders will have to be more mindful of what they put into the digital world—because there will always be those who care nothing for the health and unity of a local congregation but are more than willing to stir up mobs against faithful pastors and churches simply trying to navigate ministry in a world of chaos.

A Call for Discernment

We tend to assume that more communication and greater transparency are always good. But Carr warns that too much communication subverts itself. He writes:

“We need communication, and we need protection from communication. The reasons go beyond matters of personal integrity and agency. Without limits, excessive communication triggers defensive, antisocial reactions on the part of individuals and groups.”

This is why I regularly encourage pastors not to livestream all their worship services or store them all online indefinitely. We must reserve space and privacy for a pastor to speak to his congregation without the fear of online scrutiny from strangers. We also need to recover the discipline of distinguishing between disagreements over how a sister church is going about their business, and the disagreements that require separation for the sake of integrity and conscience.

Perhaps most importantly, we need to fight the “dissimilarity cascade” that Carr describes—the tendency for annoyances and offenses to accumulate, causing us to fixate more and more on the areas of difference with our sister churches until we forget all the commonalities that made us a family to begin with.

Hope for the Future

If denominational and network life is going to survive the digital age, we need better habits, better impulses, better instincts. I hope we can rethink our positive leanings toward making everything visible and accessible online, and resist some of our initial reflexes when we encounter errors and problems, so that we’re able to still lock arms with churches both like and unlike our own, in order to fulfill the work of the Great Commission.

Trevin Wax is vice president of research and resource development at the North American Mission Board and a visiting professor at Cedarville University. A founding editor of The Gospel Project, he is the author of multiple books, including The Thrill of Orthodoxy. He has taught courses on mission and ministry at Wheaton College and has lectured on Christianity and culture at Oxford University. His podcast is Reconstructing Faith.

Topics: