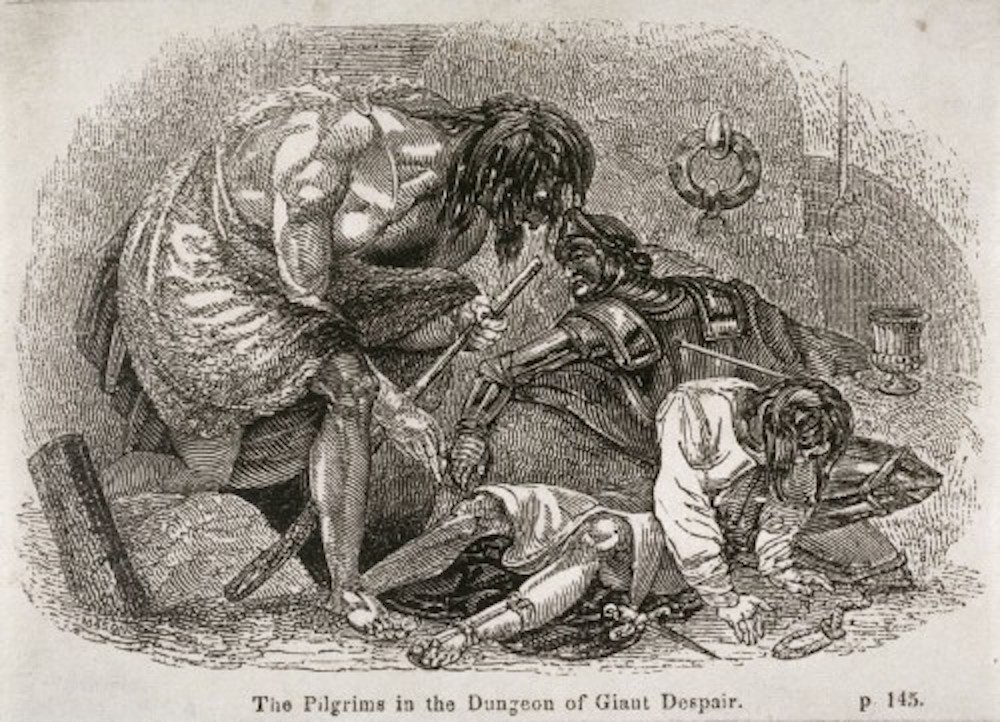

Upon falling into the hands of Giant Despair, Christian and his friend Hopeful were imprisoned without any provisions for days on end and while enduring beatings. In John Bunyan’s 17th-century allegory Pilgrim’s Progress, Christian eventually laments, “Brother, what shall we do? The life that we now live is miserable. For my part, I know not whether it is best to live thus, or to die out of hand. My soul chooseth strangling rather than life, and the grave is more easy for me than this dungeon (Job. 7:15).”

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: