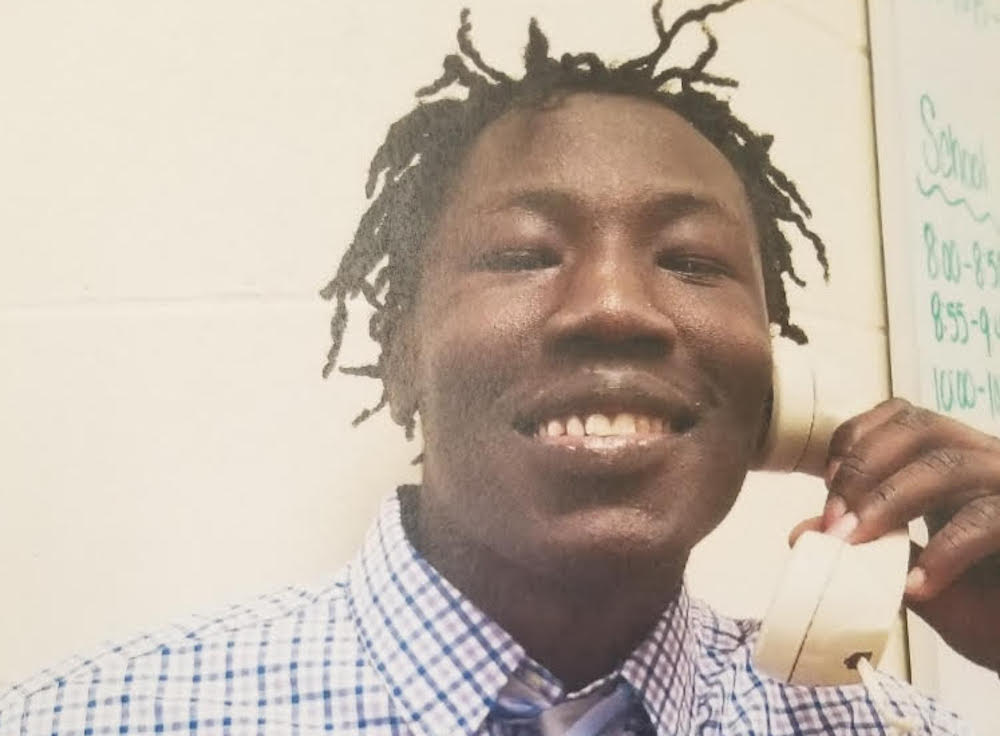

This is a bit of an unusual post for us. Here’s the story: Through my church I recently became aware of a refugee situation in Lincoln involving a young South Sudanese man named Emmanuel Chol who recently lost his refugee status due to a couple charges of felony robbery that he pled guilty to as a 16-year-old.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: