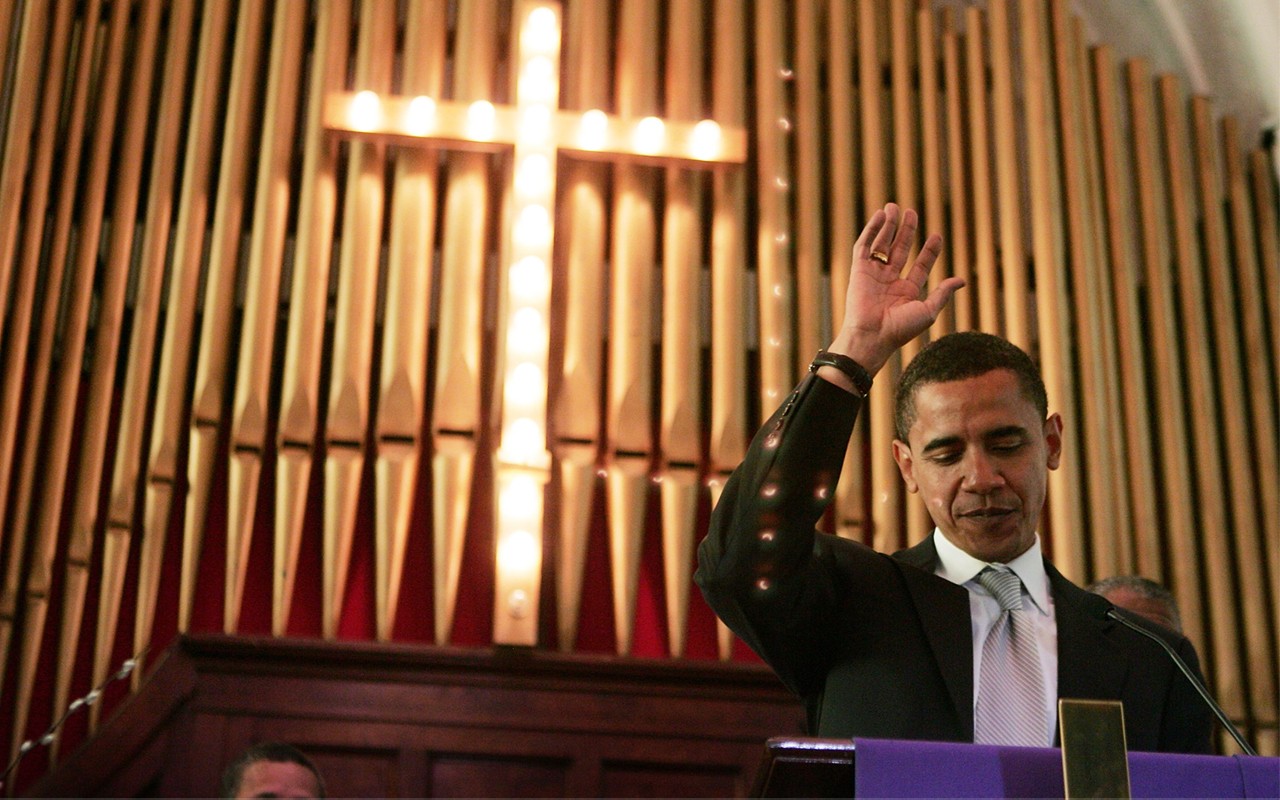

In Reclaiming Hope Michael Wear has written an engaging, clarifying work that nevertheless fails because it does not properly distinguish between a person’s testimony and their political theology. As such, the book often begins well before veering off into needless ambiguity due to a fundamental failure to approach politics in a way that is distinctly Christian from top to bottom. We’ll begin this review by considering what the book does well before explaining how these good starts routinely veer into ambiguity due to the functionally secularist political theology which animates the book.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: