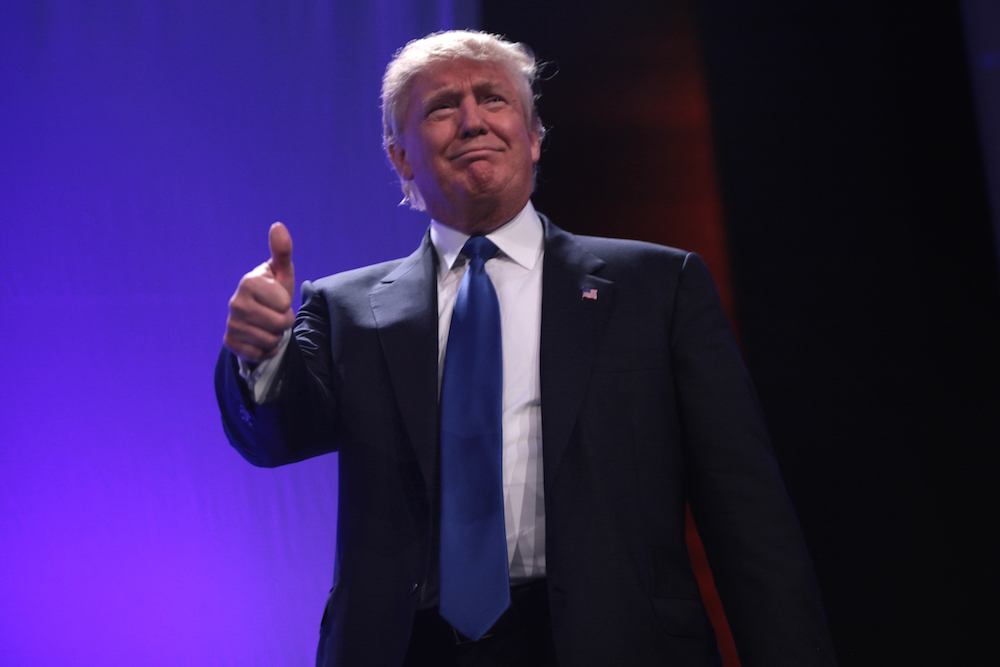

I’m pleased to run this guest piece by S.D. Kelly, particularly given the direction the Trump campaign has gone in the past week.

A dozen years after his death, the ideas promoted by the historian and philosopher Jacques Derrida still wield a powerful influence. This holds true even for people who have never heard of Derrida. In fact, it might even be especially true for people who have never heard of Derrida. During his superstar academic career, Derrida wrote thousands of pages and lectured to thousands of students, dismantling the constructs of a very logocentric world through the philosophical and critical approach of deconstructionism.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: