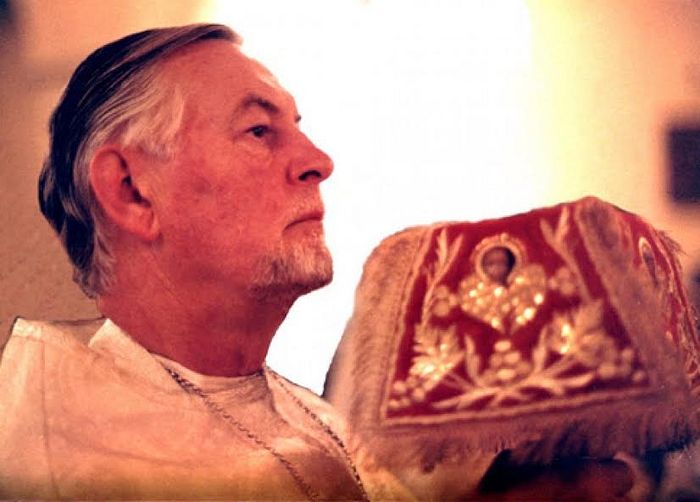

Alexander Schmemann is a window into a theological world much different than typically encountered in American evangelical circles. With a faith firmly grounded in the Russian Orthodox theological tradition and speaking determinedly into late-modern Western life, Schmemann has intrigued many readers with his paeans to the sacramentality of creation and emphasis on liturgy. In this essay, I engage with Schmemann from the Reformed theological tradition. Such a project could take many forms, so it is helpful to be clear about the goal of such a study. I come to Schmemann as a Reformed theologian specializing in my tradition’s historical and dogmatic theology, and I am temperamentally less inclined towards his more intuitive and associative theological style. However, I encounter Schmemann neither as a fanboy nor a critic per se; I hope rather to offer a good faith account of what I find in Schmemann’s work that resonates particularly with the Reformed tradition and seems conducive to broader Christian faithfulness in late modernity. I do not claim any special expertise or academic knowledge of Schmemann, nor am I seeking to compare the Reformed tradition and Eastern Orthodoxy more broadly. Rather, I will engage Schmemann’s thought with theological hospitality as if reflecting on sitting at the feet of an elder theologian and seeing what one has learned, even if this was not necessarily what he or she sought to teach.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.