Blessed are those who dwell in your house, ever singing your praise! Selah

-Psalm 84:4

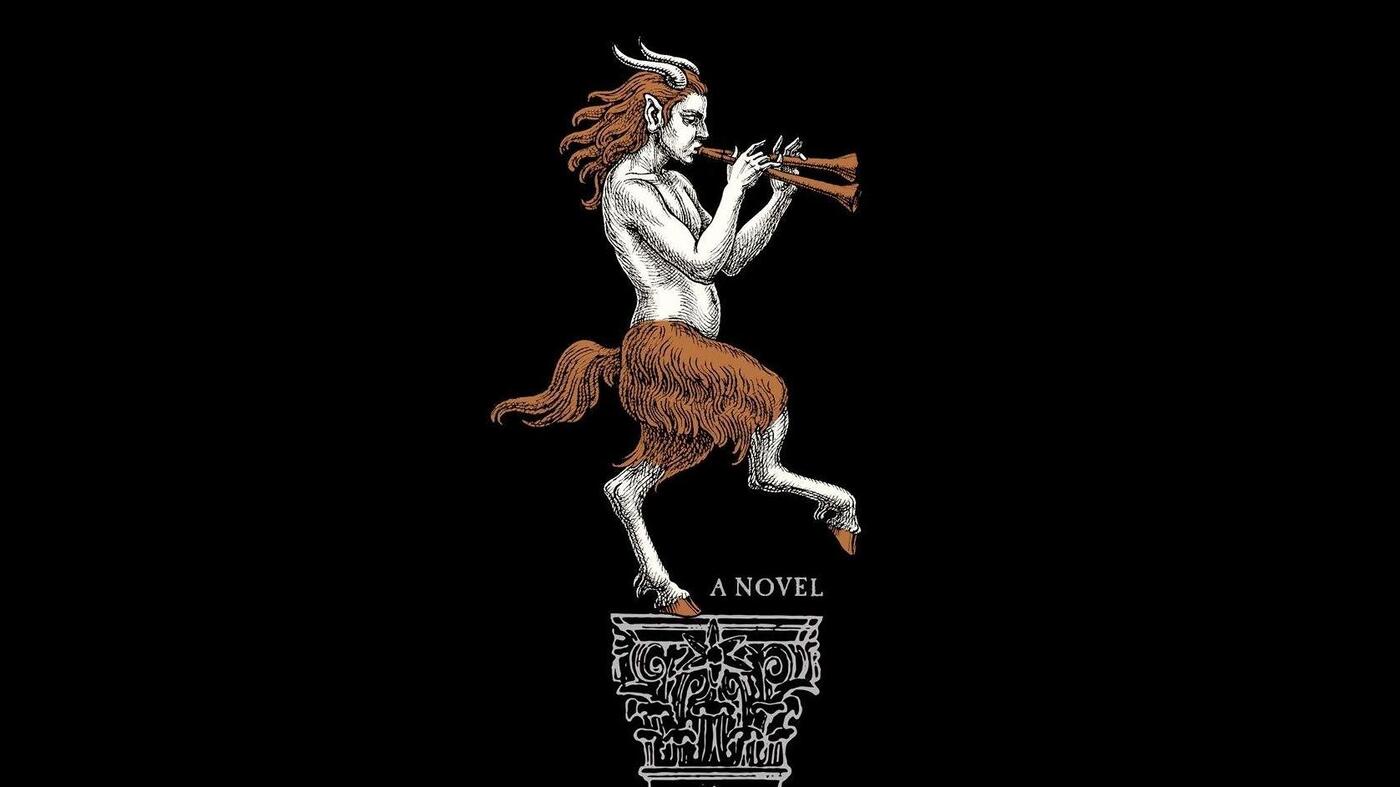

Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi is a novel open to myriad interpretations. One reading of the story is as a parable helping us rediscover the integrative power of the Christian story in the search for knowledge and meaning. After a brief description of the novel (with no spoilers, I promise!) I’ll provide some reflections specifically aimed at Christians within public universities.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: