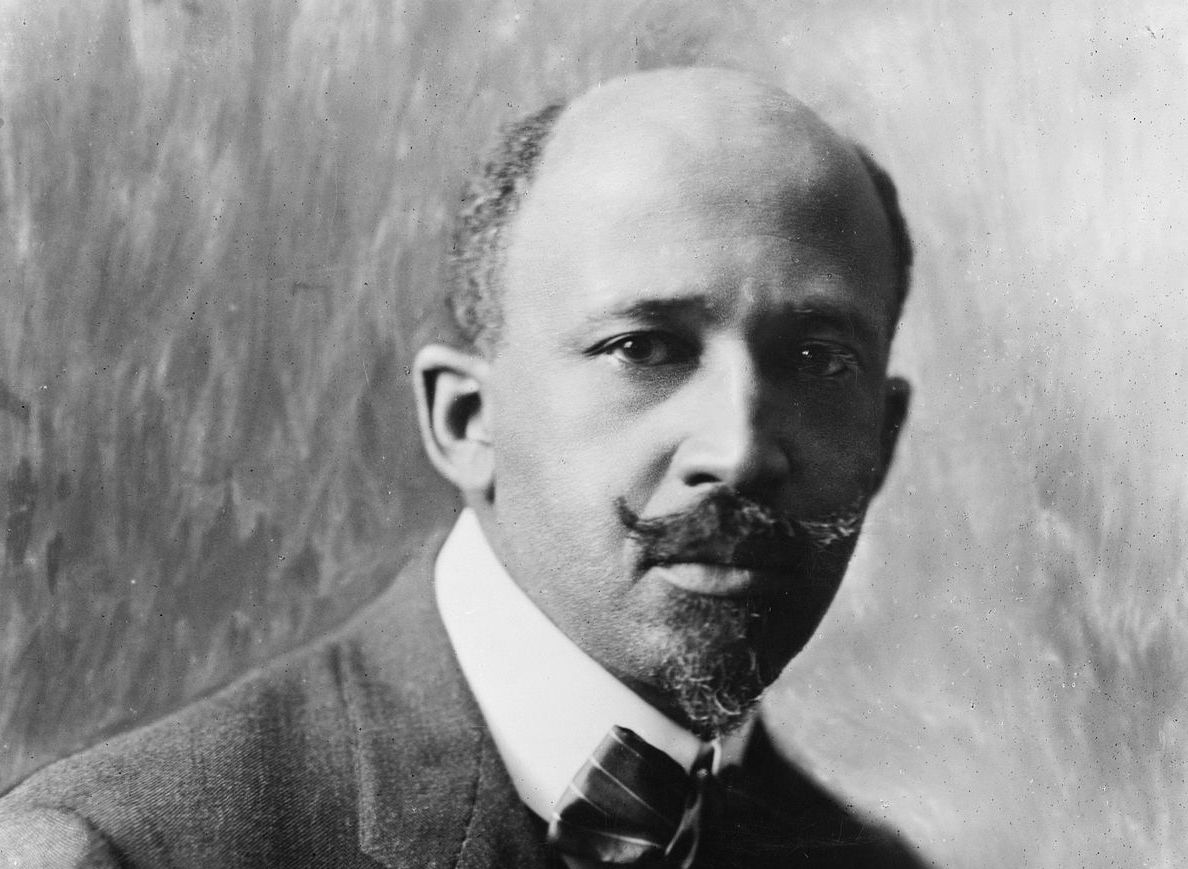

We’re continuing our exploration of Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk today with a brief overview of chapter three. Chapter three may well be one of the most timely in the entire book. Though primarily about Booker T. Washington, the issues that Washington’s work raised as well as Du Bois’s response read like something much more contemporary.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.