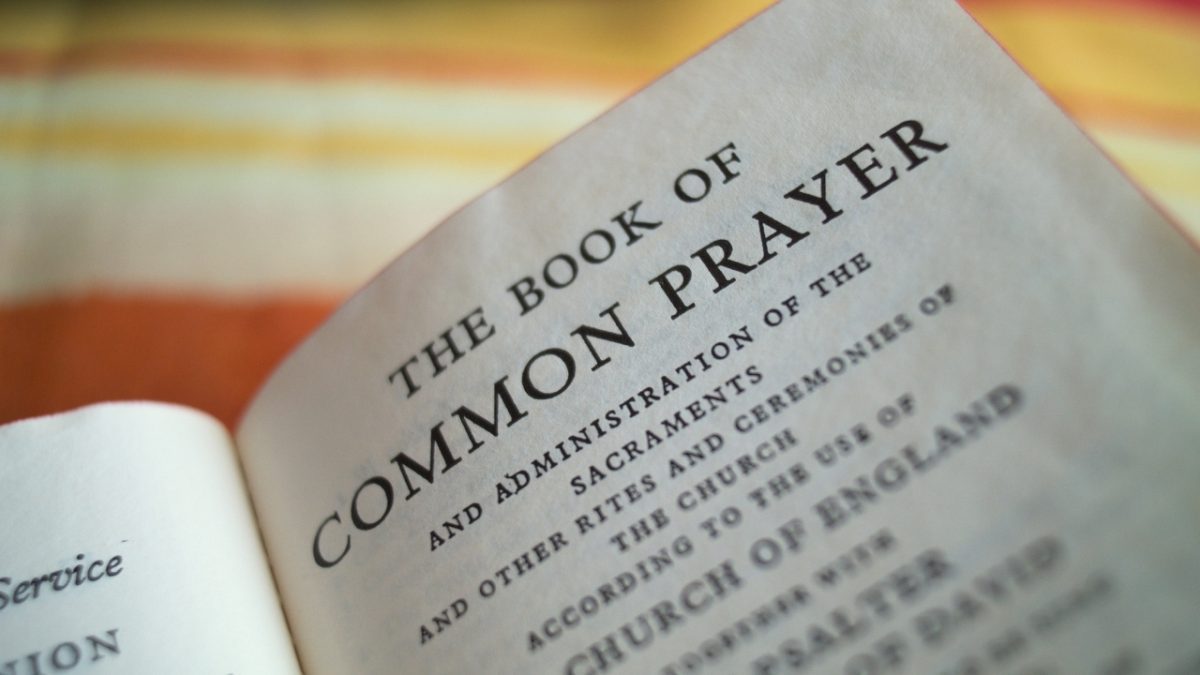

The rise in popularity of liturgical church has put new urgency to an old question.[1] Here’s a rather common scene; visitors arrive at a more liturgical church for their first visit and find a new experience, a new experience of an old, old way. It’s a bit different, but winsome and powerful nonetheless. After weeks or months of attending, the practices and power of the church sink into their bones and they’re hooked. They like the church, its ethos, what it stands for—but there is a problem, those high-church people baptize babies and that’s just not right. What happens then?

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: