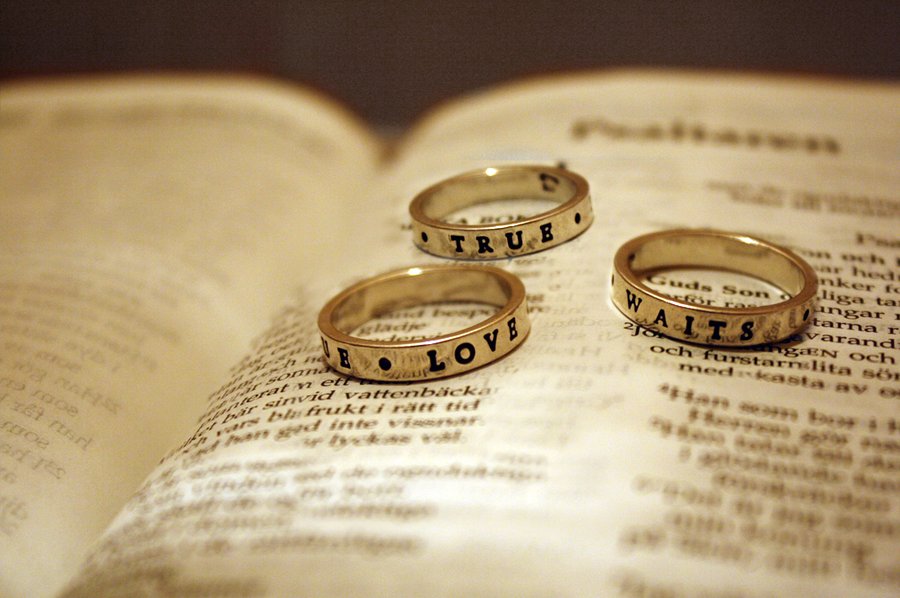

After Ruth Graham’s interview with Joshua Harris last week in Slate there was, once again, the predictable round of discussion on social media and in the blogosphere about evangelical “purity culture,” as it existed in youth ministries during the late 80s through the early 2000s. The term purity culture is probably part of the problem here, as there isn’t just one “purity culture” in evangelicalism.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: