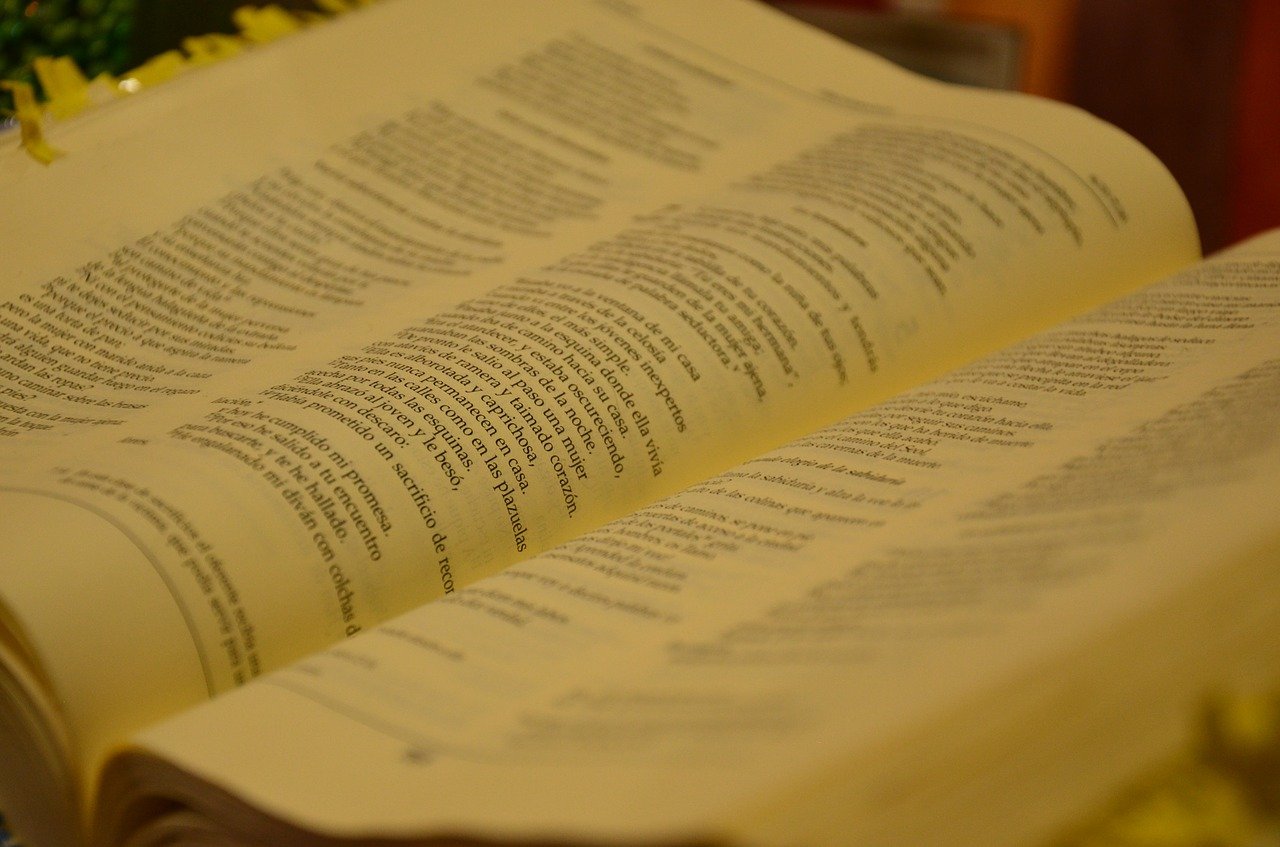

“How I love your torah, O Lord!” (Psalm 119:97)

Love for torah is always fittingly strange by the grace of God. But I am concerned that literacy of and love for the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament among North American Protestants is in decline. Here I outline three possible reasons why this is the case, and offer suggestions for a path forward.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.