Originally published May 26, 2023

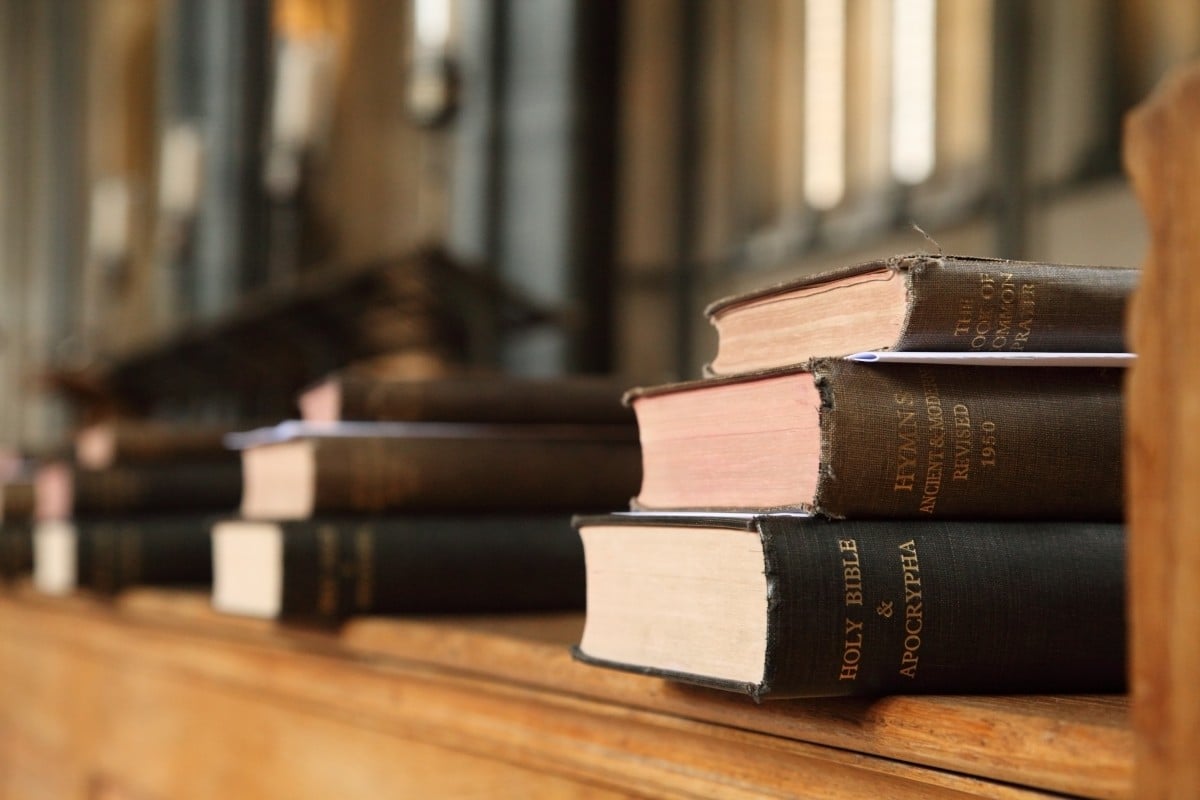

Do pew Bibles matter? Churches of all styles have had to ask this question in recent years. The increase of church plants using secular spaces for worship means that church planters must contemplate the extra weight, hassle, and expense of providing Bibles for their congregants each Sunday. The rise of technology means that many congregants come to church with merely their phone for a Bible. On top of those societal factors, the pandemic forced most churches to remove pew Bibles for a season, leaving room to reevaluate their utility in worship.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.