Explainer: Three Strategies for Family Policy Reform

February 18th, 2021 | 11 min read

Pity the poor tax code. Its drab cells and spreadsheets can’t bear the amount of moral weight we bring to bear on it. Whether, or how, to provide benefits to parents immediately raises all sorts of questions about the dignity of work, the respect due homemakers, and long-term outcomes for children in poverty.

The United States’ legacy of funneling social benefits through the tax code makes this somewhat inevitable, and these debates are often colored by one’s preexisting political preconceptions. But with all the big-picture concerns about work disincentives, green eyeshade mumblings about the debt, and (justifiable) moralizing over our nation’s high rate of child poverty, the tax code’s actual impact on low-income families sometimes gets obscured.

Before examining three proposals for child benefit reform, let’s first understand how the Child Tax Credit (CTC) currently works. Right now, each child claimed on your taxes reduces your tax liability by $2,000, so long as a family makes less than $400,000 annually (or $200,000 if a single parent.) Simple enough for the middle- and upper-middle class.

What happens if you don’t make enough income to have taxes to wipe out? After the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, families can get up to $1,400 refunded to them – in IRS argot, that’s “Additional Child Tax Credit” (ACTC.) But many eligible families get less than the full amount due to insufficient earnings. The ACTC can be claimed at a rate of 15 cents on every dollar earned after the initial $2,500 in income, up to the maximum amount ($1,400 multiplied by their number of children.)

A bit of a mouthful? Yes. And that’s even before tackling the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which boosts earnings for low-income workers, or the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC,) which reimburses a percentage of child care expenses for families with all parents in the workforce.

This tangle of programs for low-income parents used to be seen as a feature, not a bug. “In the old days, we thought that the more complex things were, the better targeted they would be,” economist Diane Schanzenbach told the New York Times. “We’ve learned in the last 20 years that the more complex things are, the more likely the worst-off people will drop out.” When evaluating the three alternatives on the table, one factor to keep in mind should be the extent to which it prioritizes simplicity.

The first, and most likely to pass in the short-run, is the expansion proposed by the Biden administration as part of their coronavirus recovery package. Other options are based off of the longstanding proposal advocated by Sens. Marco Rubio (R-Florida) and Mike Lee (R-Utah*), as well as the one recently introduced by Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah.)

The Biden Plan

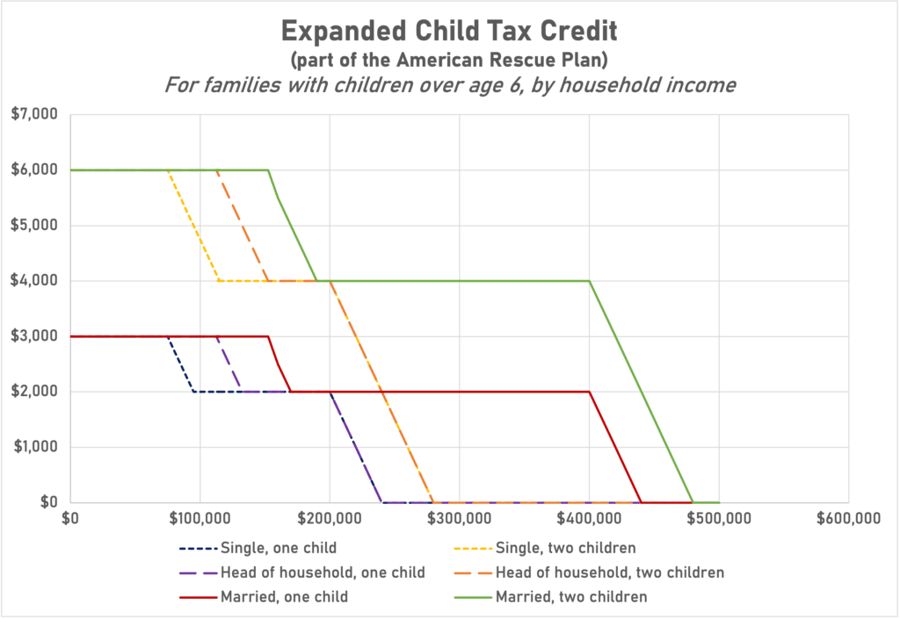

The Biden proposal, part of a broader coronavirus relief package, would layer on a $3,000 boost to the CTC for parents making less than $75,000 single/$150,000 jointly. It would initially only be available for one year (though everyone expects that once introduced, it would be very difficult, politically, to not extend.) For households with kids over 6 years old, the Biden plan CTC would look something like this:

The Rubio-Lee Plan

For years, the Rubio-Lee plan represented the most aggressive CTC expansion package on offer from the political right. Starting with the first dollar of earnings and phasing in at 15.3 cents on the dollar, families would receive up to $2,000 in ACTC. (The two senators recently suggested their willingness to expand the credit to $3,500 for older children, $4,500 for younger ones.)

The Romney Plan

Romney’s Family Security Act, which took the world of social conservativism by storm upon its introduction, would simplify the tangle of tax code benefits for low-income families into one monthly payment of $350 for kids 0-5 and $250 for children 6-17. It would remove dependent adjustments from the EITC, streamlining it, and eliminate the CDCTC (as well as some safety-net programs) to help pay for the more generous benefits.

What would each plan mean for American families?

It’s easy to get lost in phase-ins, phase-outs, and plateaus. To illustrate what these plans might mean in the lives of low-income parents, I constructed a few vignettes based on real-life circumstances families may be in. While the details are fictional, they’re based on the median wage for each job discussed, and reflect a slice of reality for many working-class Americans.

- Armando and Adrianne have a newborn, a two-year-old, a five-year-old, and an eight-year-old. Armando works at a textile plant making $27,790, putting them just under the 20th percentile for household income (if you lined up all American households in a row by income, they’d be about one-fifth of the way from the end.)

- Beatrice and her two teenagers live by themselves; she’s a home health aide who makes $24,470 annually (in the 15th percentile.)

- Charles and Carrie have a 4-year-old and a 9-year-old; they both work in the food service industry for a total of 30 hours a week, bringing home a combined $16,182 annually (in the 10th percentile).

- Dawson is a single mom with two boys, age 3 and 1. She leaves them with her mom three days a week so she can work as a cashier, where she makes $10,642 annually, putting her just above the 5th income percentile.

The following table shows how each proposal would change how much each household receives in benefits, while the bottom row shows how much each family currently receives in EITC, CTC, and ACTC.

Table 1: Total Benefits from Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, and Additional Child Tax Credit

| Armando and Adrianne | Beatrice |

Charles and Carrie | Dawson |

|

| 4 kids (ages 8, 5, 2, 0) | 2 kids (ages 13 and 15) | 2 kids (ages 9 and 4) | 2 kids (ages 3 and 1) | |

| Household income (percentile) | $ 27,790 (19th) |

$ 24,470 (15th) |

$ 16,182 (10th) |

$ 10,642 (6th) |

| Biden | $ 19,693 | $ 10,621 | $ 12,428 | $ 11,456 |

| Romney | $ 18,000 | $ 8,000 | $ 9,898 | $ 10,116 |

| Rubio/Lee | $ 10,529 | $ 9,037 | $ 8,304 | $ 5,884 |

| Current | $ 10,071 | $ 8,062 | $ 7,880 | $ 5,477 |

These vignettes are obviously reductive (abstracting away from state taxes and benefits, or participation in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, which varies from state to state and would be zeroed out in the Romney plan,) but illustrates some of the trade-offs the different plans are dealing with.

The Biden proposal is the most generous, with its universal, uncapped benefits for low-income households. It would, however, require filing a tax return, which could miss some families. Armando and Adrianne would see the equivalent of an additional paycheck a month, and Dawson would see her income increase by 70 percent compared to her current market income and benefits.

The Rubio/Lee option is self-consciously tailored to reward work; the phase-in against earnings means families miss out on benefits compared to the more universal plans. It’s a marginal change towards providing more support, rather than the transformative Romney proposal or the big spending of the Biden plan. Their approach would make sense in a time of incrementalism but comes across as pallid next to the bolder ideas in the wake of Covid-19.

Romney’s Family Security Act is especially beneficial to families with younger children, like Dawson. Armando and Adrianne actually bump against the cap ($15,000 in child benefits) in the Romney plan. Unlike the Biden plan, it would be paid through the Social Security Administration, lowering the risk of missing families who don’t file taxes.

The generosity of the Biden and Romney plans could be salutary or worrisome if you believe unconditional cash benefits likely to recreate some of the problems of pre-1996 welfare programs. If you think America is too punitive towards family formation and have an eye towards our record-low fertility rates, Biden or Romney might appeal (acknowledging that child benefits do not automatically translate into markedly higher fertility rates.) Concerns about subsidizing single parenthood and discouraging labor-force participation, however, help incline some analysts towards Rubio/Lee or the status quo.

The Biden plan puts the most money in the pockets of low-income parents but does so by pumping money into a creaky system without reform; acceptable as a one-year emergency measure, but a missed opportunity to make the tax code work better.

Which leaves my sympathies with the Romney plan. A universal benefit rewards parents for the work of rearing the next generation and provides assistance to poor kids without holding them hostage to the labor force status of their parents. Portioning out the child benefits converts the EITC to a more straightforward low-wage work supplement, reducing most marriage penalties, and making the tax code more legible to low-income families.

Ultimately, the poetry of rewarding work or incentivizing marriage bumps up against the prose of Schedule 8812, Line 7A, and ACTC phase-in rates. A saner, more generous child benefit system would help stabilize low-income families and would do so in a responsible way. New challenges call for new approaches, and the challenges facing working-class parents today call for a child benefit, coupled with tax reform, proposed under the Romney plan.

*In the interest of full disclosure, I worked for the Joint Economic Committee as a senior policy advisor for two years, during which Sen. Lee served as chairman.

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Topics: