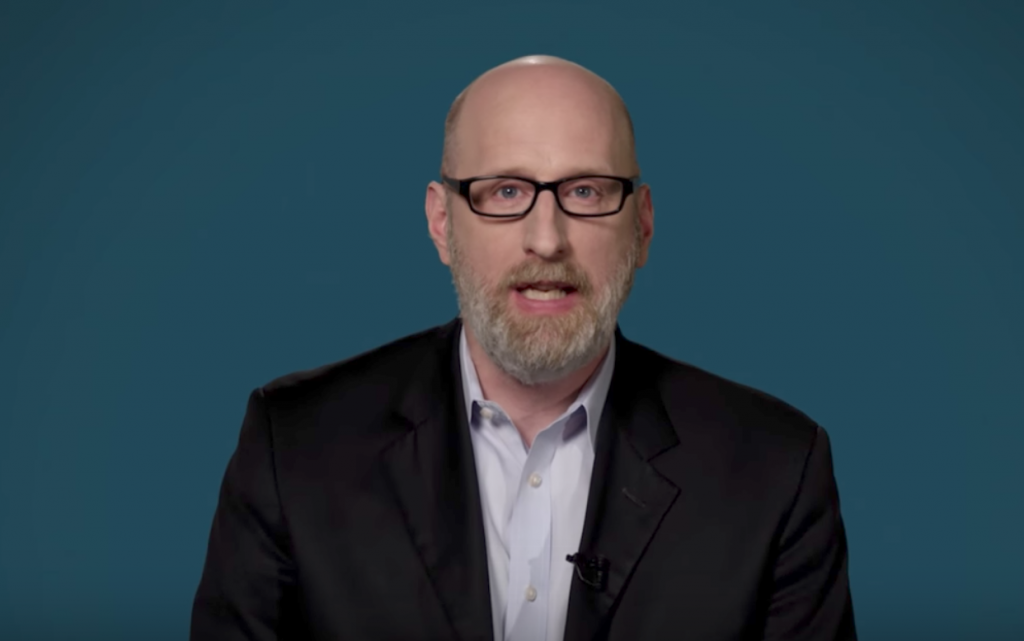

In his sharp response to Sohrab Ahmari’s attack on his approach to politics, National Review writer David French noted that Ahmari’s attack hinged on two bizarre fictions:

First, the fiction that French himself is a timid milquetoast classical liberal who lacks the will to fight liberalism in a sufficiently comprehensive way.

Second, the even more ludicrous fiction that Donald Trump represents a sufficiently radical critique of liberalism to fully address the crisis of the moment.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.