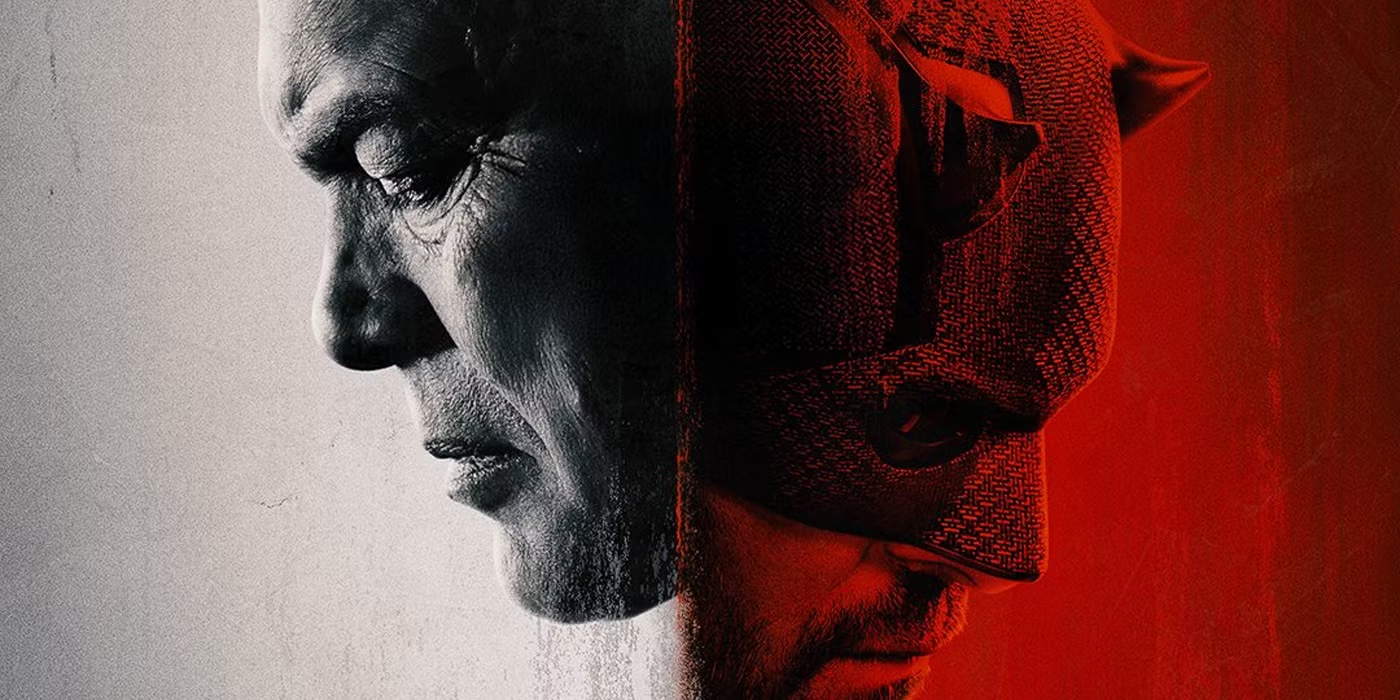

When Netflix released the original Daredevil show in 2015, it stood out (like its other Marvel shows, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, and The Punisher) because it was interested in the moral lives of its characters. The problem these particular shows (which can in many ways be talked about separately from the broader Marvel Cinematic Universe) found endlessly fascinating was what it meant to be a good person in a morally ambiguous world.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: