Hear the word of the Lord from Luke 1:

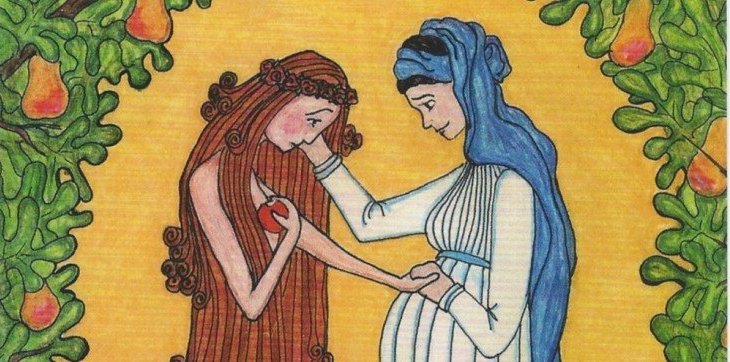

In the sixth month of Elizabeth’s pregnancy, God sent the angel Gabriel to Nazareth, a town in Galilee, to a virgin pledged to be married to a man named Joseph, a descendant of David. The virgin’s name was Mary. The angel went to her and said, “Greetings, you who are highly favored! The Lord is with you.”

Mary was greatly troubled at his words and wondered what kind of greeting this might be. But the angel said to her, “Do not be afraid, Mary; you have found favor with God. You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end.”

“How will this be,” Mary asked the angel, “since I am a virgin?”

The angel answered, “The Holy Spirit will come on you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. So the holy one to be born will be called the Son of God. Even Elizabeth your relative is going to have a child in her old age, and she who was said to be unable to conceive is in her sixth month. For no word from God will ever fail.”

“I am the Lord’s servant,” Mary answered. “May your word to me be fulfilled.” Then the angel left her. (Luke 1:26-28)

The story of salvation reaches a culminating point right here—with the moving of God into the world in the person of Jesus Christ. At Christmas we remember: the babe in the womb, “incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary” as the Creed declares—this one, the one called “Son of God”, has come to take up space in our world. In Christ, God has drawn staggeringly near.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.