“Christianity should never give any onlooker the right to conclude that Christianity believes in the negation of life.” — Francis Schaeffer

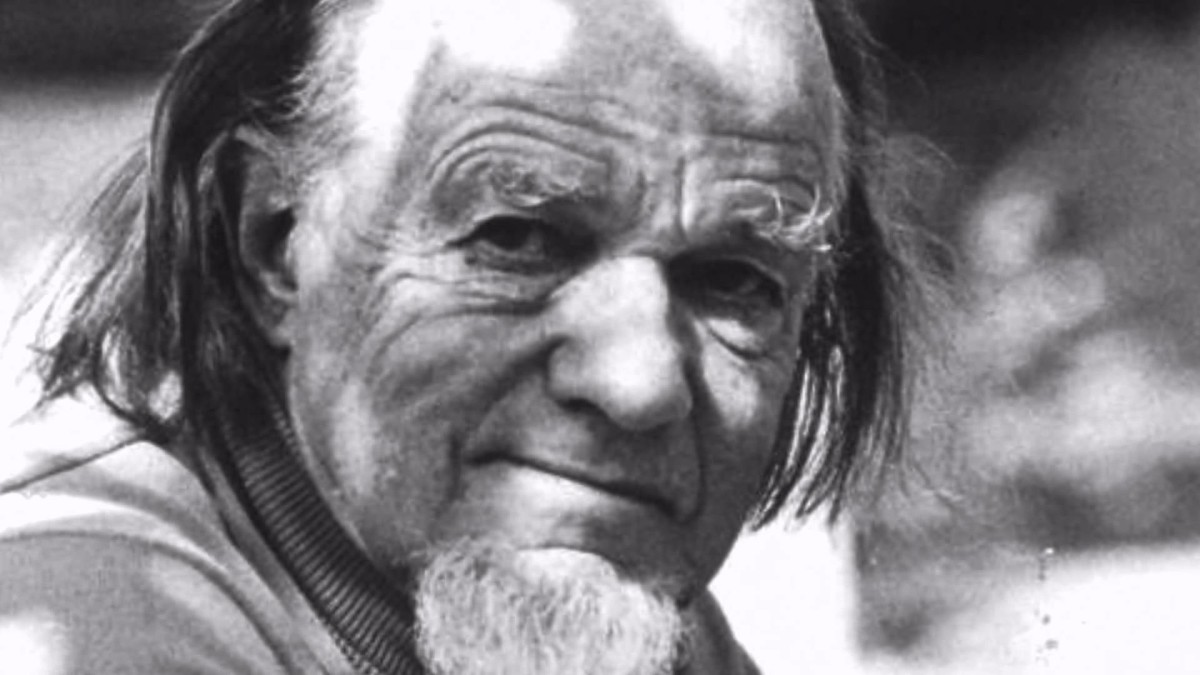

I’ve often wondered what might happen if Josh Ritter, one of my favorite modern songwriters, were ever to meet Francis Schaeffer, the famous American pastor and intellectual who in 1955 founded L’Abri in the Swiss Alpine village of Huemoz.

If you spend any length of time listening to Ritter’s music (and you really should spend some time with it) you’ll quickly realize that the man is simultaneously fascinated with religious themes and repelled by what he has seen of Christianity and of the Christian god.

In this sense he fits neatly into the category of “misotheist” as described by Bernard Schweizer. For Ritter the issue isn’t necessarily whether or not God exists. Rather, the issue is that if there is a God then he is a cosmic killjoy, a tedious bore of a being who would create us with the capacity to love and then fence it about with so many rules that the joy and wonder of it all is snatched away.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.