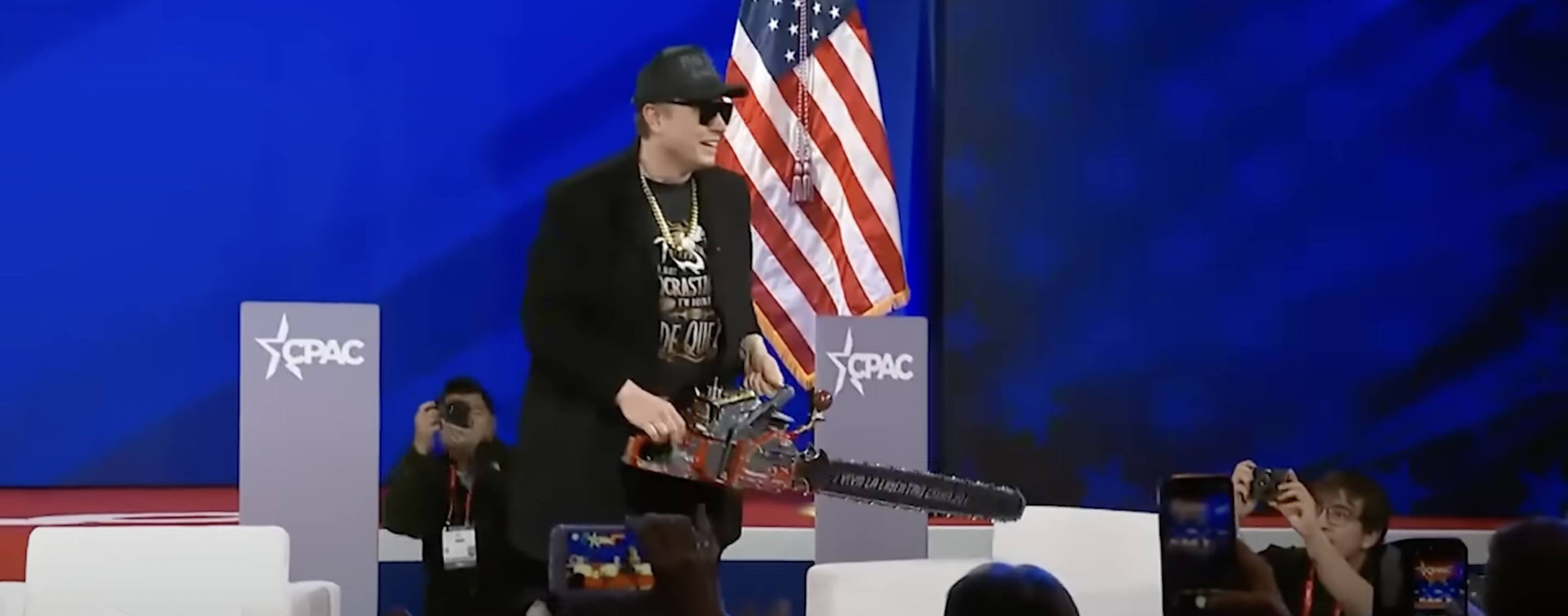

The aggressive actions by President Trump’s newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) startled many commentators. But Elon Musk’s frenzied assault on the federal civil service reflects the popularity of anti-government ideas that have gradually gained a wide acceptance among Americans in recent decades. Talk radio and, more recently, cable news, and social media have been highly effective platforms for spreading libertarian ideas.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: