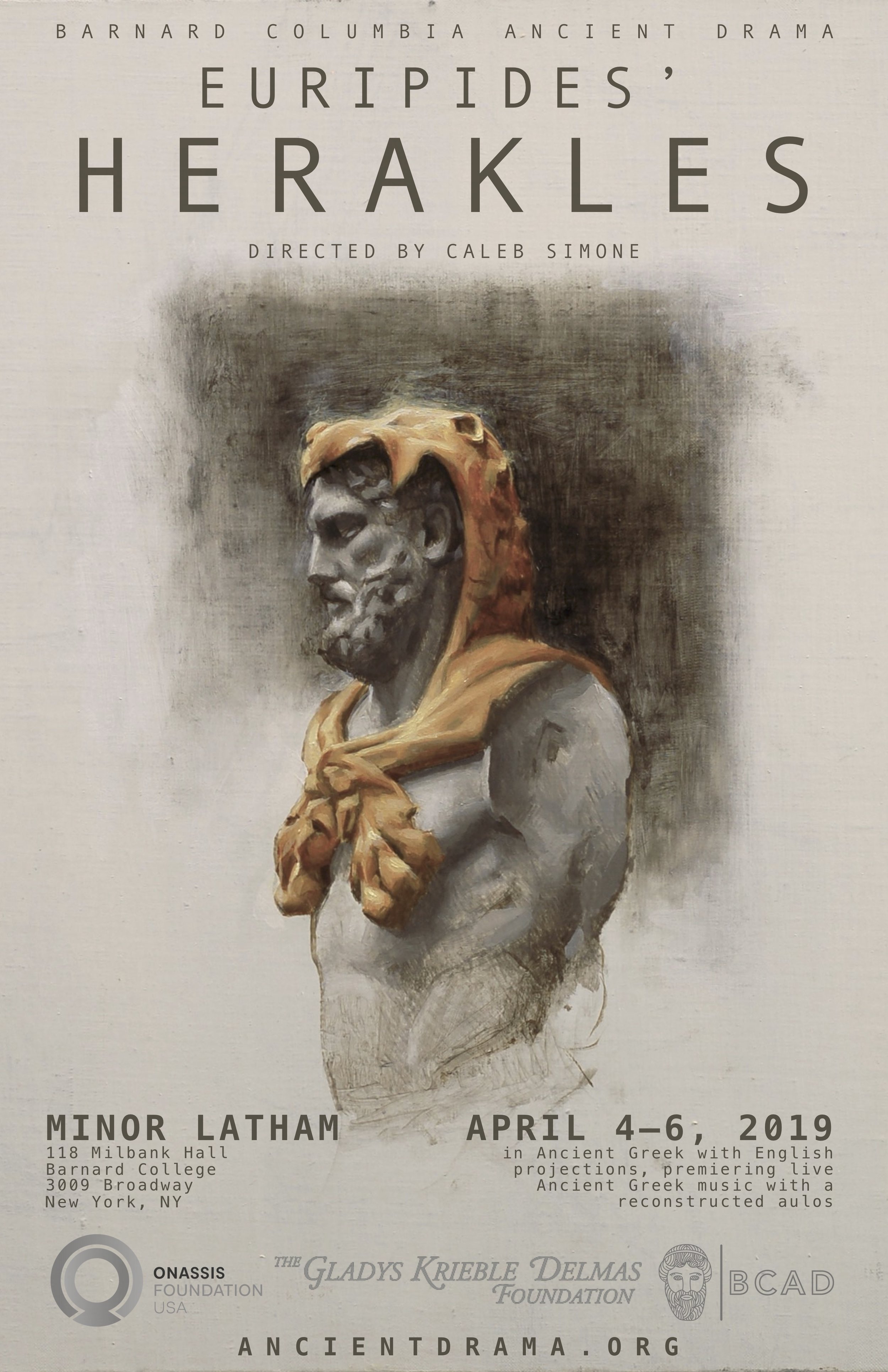

Several months ago, I went with a group of friends– mostly church people, from Emmanuel Anglican– to see a production of Euripides’ Herakles, in the original Greek, directed by our friend Caleb Simone. It was part of his doctoral work, with reconstructed music and choreography, and felt like nearly a church project: one of Caleb and Ashley’s sons played one of Herakles and Megara’s children; our pastor’s eldest son played another; our friend Edmond Rochat did the painting for the poster; half the people there were Christian.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.