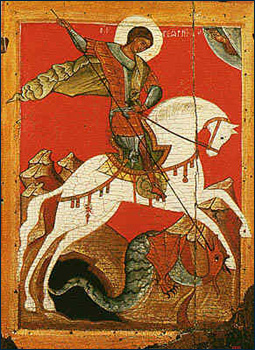

St. George is an unlikely candidate for “saint most likely to promote tolerance and ecumenical understanding” these days. The legendary soldier is most often pictured astride a gallant warhorse, nobly piercing a large dragon with his lance or spear while an appreciative townspeople and adoring (and rescued) princess stand aside in the background. It is the paradigmatic picture of the victory of good over evil and besides carring heavy moralistic and absolutist overtones, it glorifies in the death and punishment meted out at the the iron-gloved hand of the military saint.

St. George is an unlikely candidate for “saint most likely to promote tolerance and ecumenical understanding” these days. The legendary soldier is most often pictured astride a gallant warhorse, nobly piercing a large dragon with his lance or spear while an appreciative townspeople and adoring (and rescued) princess stand aside in the background. It is the paradigmatic picture of the victory of good over evil and besides carring heavy moralistic and absolutist overtones, it glorifies in the death and punishment meted out at the the iron-gloved hand of the military saint.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.