Earlier this week I introduced two major contributors to Christian just war theory—Augustine and Aquinas. Both of these men agree that a war can be just only when: it is prosecuted by a legitimate authority, is embarked upon for the sake of a just cause, and is motivated by right intentions. We looked at the first of these conditions already and will conclude this examination of Christian just war theory by summarizing the other two.

Earlier this week I introduced two major contributors to Christian just war theory—Augustine and Aquinas. Both of these men agree that a war can be just only when: it is prosecuted by a legitimate authority, is embarked upon for the sake of a just cause, and is motivated by right intentions. We looked at the first of these conditions already and will conclude this examination of Christian just war theory by summarizing the other two.

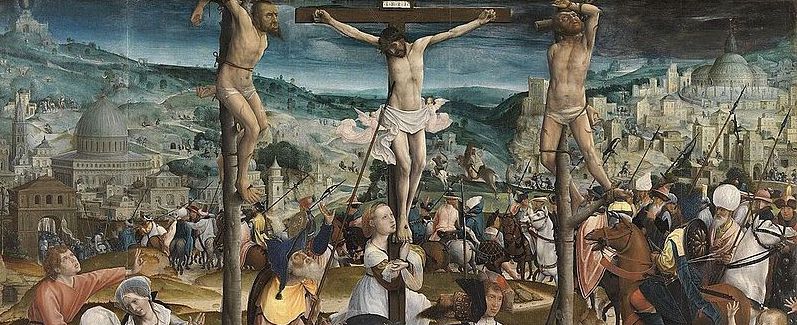

The second condition Aquinas explicitly lays out (and derives from Augustine) is that of just cause, “namely that those who are attacked, should be attacked because they deserve it on account of some fault.” This idea of entering into war with those who deserve to be punished hearkens back to Augustine’s conception of war as a tool used by God to further His ends in relationship to the nations, and even further back to the military feats of Joshua and David. Additionally, it assumes that the attackers are in the right. It is this recognition of the rightness of their situation that justifies them entering into battle. This just cause condition also rests upon the presupposition of a natural order—in which the harmony and peace that is disrupted by a wrong action must be set right again. The country prosecuting the war has the right to do so because it is restoring peace and harmony.

A consideration of the end or goal of war leads to the final condition set forth by Aquinas and Augustine. Aquinas and Augustine argue that a war is just only if it is carried out with right intentions (in conjunction with the previously mentioned conditions). These intentions are broadly the same for both theologians; the aim or purpose of the just war is to bring about peace, or to advance what is good and avoid what is evil.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.