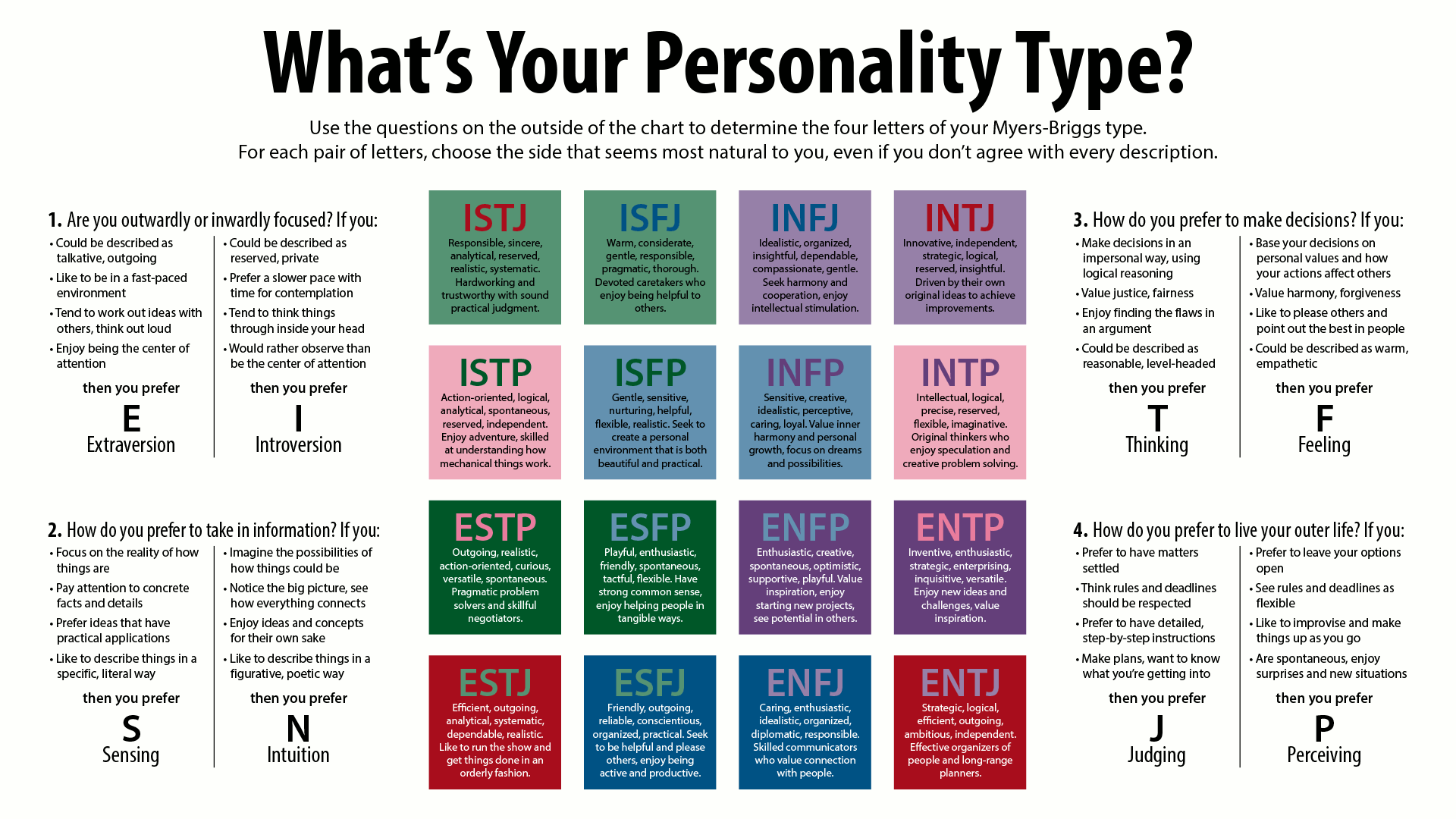

Morgan Guyton recently posted a piece entitled ‘Why English Majors Make Lousy Fundamentalists,’ which was also crossposted on Jesus Creed. Within it, he begins by arguing that different readings of Scripture ‘may end up boiling down to different personality types.’ As an INFP—‘the personality type of a poet, or an English major, or perhaps a romantic’—Guyton believes that he brings certain instincts to the reading of the Bible that rub ‘fundamentalists’ up the wrong way.

Login to read more

Sign in or create a free account to access Subscriber-only content.

Topics: