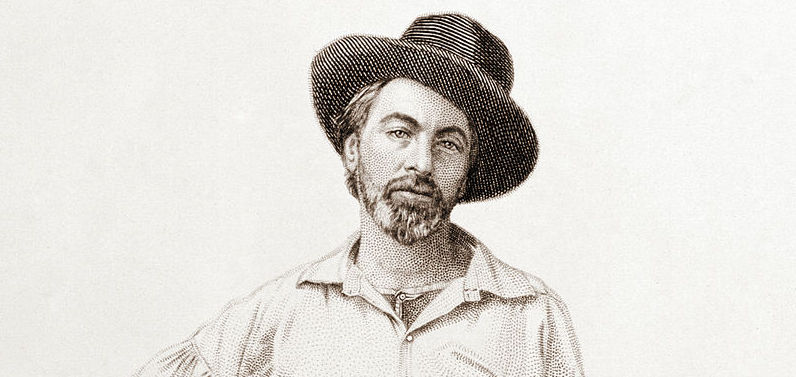

Walt Whitman on Neighbors and Strangers

March 10th, 2016 | 10 min read

It is good to remember, especially in light of these presidential primaries, that no era is without its share of baffling endorsements. Andrew Carnegie, whose imperious steel mills did more than perhaps anyone to antagonize the neo-transcendentalist folklore of Leaves of Grass, called Walt Whitman the greatest poet America has produced.

Out of the many poems Whitman wrote on the effects of industrial change, perhaps none is as poignant as “To A Stranger.”

In the poem, Whitman deconstructs the concept of “stranger,” using the language of warmth, intimacy, and closeness to contrast against the usual associations our minds make about strangers. The paradox is that Whitman speaks of the passing stranger as though he or she (the poem does not reveal) were his lifelong friend. From where is Whitman sensing this connection?

Whitman directs his poetic imagination toward a counterfactual: If life had been different, wouldn’t their relationship also be?

Observing the stranger, Whitman sees past the distance society has placed between them and contemplates having lived a life in close proximity, in friendship, in romantic relationship even, with him or her. Whitman redefines the concept by suggesting that being a stranger is contingent on how society is ordered.

By the time Whitman was writing, large scale urbanization is underway, obliterating the relational categories that had characterized communal life since the country’s founding. One of the effects of mass movement away from rural America and into dense urban environments was a shift in how Americans related to each other as fellow residents. Over time, the knowability of those with whom one shares a space is challenged by the demands of city living.

It began to be obvious, after a while, to the new inhabitants of our country’s emerging urban centers that knowing the inhabitants of one’s city with the kind of depth available to those in rural contexts is no longer possible. There are just too many people. A city of strangers. But where are the neighbors?

Whitman realized something. A stranger is only seen as such due to the sociological circumstances of urbanization. In another context, the same person who is now a stranger would have been a friend, a neighbor, a lover. This is the force of Whitman’s line: “I have somewhere surely lived a life of joy with you.”

Had Whitman and his stranger lived in the country, the two would have been in each other’s lives in a far more significant way. Whitman’s point is that the historical accident of living in a densely populated city has altered the dynamics of how human beings relate to each other. We have not undergone an intrinsic change; what has changed is an external circumstance, prompting an artificial modification in human relatability.

This is why, according to Whitman, it’s a mistake to treat strangers as fundamentally distant and unfamiliar. We need a conceptual distinction between a neighbor and stranger, sure, but if our view and posture toward strangers is characterized by seeing them as ultimately other, we have misunderstood an extrinsic change as an intrinsic one. If city-dwellers are used to being unknown by the majority of persons they encounter, this is because something external has acted on them, not because something internal has shifted within them.

Our burden is to see through this newly generated communal indifference and peer into their still-intact humanity. Our burden is to resist allowing the ubiquity of strangers to efface our capacity to care about the person right in front of us. We are to look at strangers in the same way we would a neighbor in an age before the great sprawl of urban centers rearranged our ways of living.

But even though the change is extrinsic, it is nevertheless internalized. To deny that an upheaval of this magnitude at the environmental level is not going to impact the very way we conceptualize each other at the personal level is psychologically naive. Going from seeing a handful of strangers a year to hundreds per day represents a real barrier to conceiving of these unknown persons as neighbors.

Except it’s not so clear Whitman is advocating we change our behavior toward strangers. The poet’s burden is to deploy the powers of his imagination toward the recovery of truths deeply important to the human experience. Whitman notices a change and subverts it through reflection.

With that said, he is not writing Walden. Though it’s tempting to see Whitman’s poem as an indictment, we shouldn’t understand it as a critique of the city. In “Song of the Broad-Axe” Whitman is effusive about the grandeur of cities. (Then again, this may not clinch matters, since of course he famously declared: “I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.”) “To A Stranger,” rather, is a reminder to not allow the forces of mass demographic concentration to obliterate our sense of the fundamental knowability of human beings. But Whitman places that responsibility on the city’s inhabitant, not on the city itself. And the lesson is to shift our perspective, not to alter our behavior.

The city, of course, is here to stay. Whitman loved New York City, which meant this didn’t trouble him. But he did foresee that the de-neighborization of America would continue to increase, as the magnetism of cities pulled ever harder to attract greater populations. Though the poem ends by suggesting that Whitman is singling out a particular individual, this can be alternatively seen as a statement about this feature — that one can share a communal space with someone yet remain a stranger to them — becoming a fixed sociological reality.

He writes:

“I am not to speak to you—I am to think of you when I sit alone, or wake at night alone,

I am to wait—I do not doubt I am to meet you again,

I am to see to it that I do not lose you.”

I don’t take Whitman here to be ultimately referring to numerically one and the same individual. Rather, for Whitman, the notion of “the stranger” encompasses a type of person. Reading the final passage in this way transforms the statement about being sure that he will see this person again into a statement about the fact that urban centers, such as New York City, will continue to create encounters between people who are strangers to each other; will continue to be shared by people who do not know anything about each other.

Whitman speaks of the stranger’s “eyes, face, flesh” — features common to all of us. And yet Whitman focuses on the particularities of one stranger, not on the behavior of the masses. Is a stranger a neighbor deep down, or a part of the faceless, nameless mass of people for whom one never spares a thought? Whitman feels a need to humanize the stranger. In doing so he is a herald, warning us to hold on to our capacity to see this buried humanity in the passers-by.

Years later, Wendell Berry simultaneously echoed Whitman and demurred from him. He saw the same humanity-effacing mechanism at work in the machinery of urbanization, yet he did not see it as ultimately recoverable through reflection, through a change in perspective, as Whitman did. Berry:

“A community is the mental and spiritual condition of knowing that the place is shared, and that the people who share the place define and limit the possibilities of each other’s lives. It is the knowledge that people have of each other, their concern for each other, their trust in each other, the freedom with which they come and go among themselves.”

Though Berry offers a definition of community that appears to be incompatible with Whitman’s humanization of the stranger, there is an important point of convergence. Where we live impacts how we live — not in the trite sense suggested by treating that insight as a slogan. But in terms of the very categories we use for understanding fellow human beings. The poet beckons us to remain vigilant: There are forces of dehumanization at work all around us that we should work very hard to resist.

Featured image via: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walt_Whitman

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Berny Belvedere is a lecturer in philosophy and editor-in-chief of Arc Digital. He has written for the Washington Post, National Review, the Weekly Standard, and more. Follow him @bernybelvedere.

Topics: