Tomorrow I hope to publish a brief review of Laura Dunn’s new film “The Seer.” It’s a unique film and a hard one to pin down because while it is a portrait of Wendell Berry, Berry himself is never actually filmed for it. We only get archival photos of him and recordings of interviews with him. That said, what we do get is a unique film that does a marvelous job of helping viewers see what Berry sees when he looks at the world. And that is no small achievement. More tomorrow. For now, here’s the interview:

How did you first discover Berry’s writing?

I don’t remember, it was high school I think. I’d been interested in environmental issues for a long time, I’d been around agriculture for a long time (because of my mom’s job). It was mostly the non-fiction work that I started reading. When I was working on my feature “The Unforeseen,” which is very much a sibling to “The Seer”, I used a Wendell poem for that film and I met Wendell in that process and asked him to record his poem for the film. When I toured that film I was surprised at how few people knew who Wendell Berry was. When I finished I just imagined another film about his work. I thought to make a film that would in some way honor his work and his spirit and draw more attention to his work.

Were there certain essays, poems, or novels that you found yourself coming back to more often than others as you were preparing to film, do interviews, and all the other work of making this movie?

The Unsettling of America was the primary text that gave me a lot of the structure. A sense of place is huge for him so you really have to reflect the place in Henry County so that was a big part of it. So I think The Unsettling of America provided the arc of the industrialization of agriculture and how that change agricultural landscapes and communities. It seems to me that is the primary stress behind his work. But he’s also an artist and a poet and that transcends all of that and I wanted the film to reflect that so I returned to a lot of his poetry too. The film was kind of a tone poem; yeah there’s an argument, but there’s also a lot of space that is more visual and sensual which in cinematic language is more of a poetic structure. But I think if I had to say one book it would be The Unsettling of America.

One of the themes of Berry’s work is that we need to re-learn how to see the world to recover the sense of wonder, beauty, and obligation that came more naturally to us prior to industrialism. That creates a real pressure on you as a filmmaker, I imagine. How does that belief, that the way we see the world needs to change, shape the way you think about your job as a filmmaker?

The big reason I love documentary filmmaking is because I like the process of the exchange. I think there are a lot of filmmakers who have a pretty clear idea of what they want to make a story about and they go out to find the reality to confirm their world-view. I don’t do that. I don’t have a script. I don’t have a strict and rigid view when I go into making a film. I have an idea; I have values that matter to me. But really I’m trying to discover what’s there and hopefully let it change me.

In one of my meetings with Wendell, I was talking about how my opinion of something had changed based on the interviews I was doing, and he said, “That’s good. You’re the product. The film isn’t the product; you’re the product.” It was important to him that the film changed me. That’s fundamental to my approach. I go in open and hope to be transformed and changed by the material and that definitely happened. I go in and explore and get lost in the material and find my way out.

We shot about a hundred hours of footage and then it was just following our nose. I read every book I could read, I was in Henry County for all four seasons, I talked to lots of people, they told me to talk to someone else… you’re just following your nose intuitively. That approach allows for a transformation of your own lens.

I think that the other thing is that I’ve seen a lot of films about environmental issues or difficult issues and I have many young children. I wanted a landscape and a place that would be nourishing rather than just horribly depressing. I think I was encouraged. One of the big things that changed is that I went in thinking it was a film about Wendell and it really became, under Wendell’s direction, about so much more than him. I really loved the influence of Tanya Berry, how she elevated the domestic realm, how she talked about homemaking as an art. Tanya really taught me a lot about how art and homemaking can go together; you just have to allow them to. That was probably the biggest way my lens changed. A lot of the issues around farmers, rural, communities, agriculture were issues I knew pretty well but as you meet more people you become more sensitive to the complexities and it’s not just black and white. I was also totally struck by the natural beauty of rural Kentucky. We live in a time where there is such a divide between rural and urban and the urbanites think of the rural as backwards and nowhere so to really be there and see so much beauty is important; I want to bring that vision to other people so they can see it has a lot of inherent value.

I also wonder, how do you convey that vision to Lee Daniel, the cinematographer for the film?

He’s like a brother to me. We have a really familial relationship. I would say that we have a really similar orientation, it just works. He needs a lot of space; he doesn’t need someone over his shoulder. I talk about Lee in this way: I think Lee has a way of unframing things; instead of capturing something, he frees it. He’s also, like me, very interested in the natural light, natural world, the natural way things fit together. And I think most filmmakers are into control, controlling the image and sound to create a specific image in their head. For both Lee and myself we’re much more interested in letting the lens discover what’s there, letting the natural spaces fill up the frame. To do that, you have to be patient, you have to spend a long time in places with people, and you have to give people a lot of space. So we talk about ideas, but it’s not a whole lot of discussion it’s more ‘were going to this location, how much time are we there? What do you see?’ It’s a look-and-see process. His footage is one big flow so the editing of his footage is very tedious but that fits with my editing process so it works for me.

One of the early things I read about the movie, back when it was under the title “Forty Panes,” suggested that it’s a sequel to your previous documentary, The Unforeseen. Do you agree with that comment? If so, in what ways is a film about a rural farmer-writer a sequel to a film about a controversial urban development in Austin, TX?

The primary character in “The Unforeseen” is a man named Gary Bradley. He came from west Texas and in the opening of the film he talks about growing up on a farm, he talks about how you’d have one big hailstorm that would wipe everything away. It was a place where you were close to God and nature, a God who gave you great abundance at times and took everything away at times. He left that and set out to have a life where he could have more control. That was really the whole premise of “The Unforeseen.” And in the end he loses everything and he starts talking about how he really has to start walking the walk. There are some very overt themes there of God and nature and control. Wendell Berry’s poem that opens the film describes this walk where you’re walking on a man-made landscape and then there’s this pond and hope, life, and abundance and it shows how a little tiny bit of creation can be so healing and beautiful. “The Seer” is the inverse of all that. We start with this vision where everything is lost and destroyed but we transport you to a world where things are whole, to a place that is about the natural landscape.

In one review of the documentary, the author talked about how he was relatively ignorant about Berry’s work but had many friends who loved it. He said your documentary is, basically, “translating” Berry’s work into a medium more familiar to him. I’ve heard several other people make similar comments in connection to the movie—they say Berry needs translators. Was that one of the goals in making a film about Berry, a man who hates screens?

That’s an interesting question. For me, he doesn’t need translation. I read his words and they’re crystal clear. I don’t think of myself as a translator so much as a big arrow. I’m this giant arrow using the medium that so many people immerse themselves in now and saying “is there a way within that medium to point people away from the medium?” That’s part of the experiment. I don’t know yet if it worked. If you see the film, will it make people want to turn away from the screen and toward a book of Wendell Berry’s or to the natural world? That’s what Wendell would want and he was my standard.

One of the unique things about Berry’s fiction, and perhaps why some people find it less accessible, is that in many ways the books aren’t primarily about human characters but are instead about “a place on earth.” From what I’ve seen, you took a similar approach to Henry County in your movie. How did you go about trying to make Henry County, KY a character?

You know, there’s this great line that Burley Coulter says where he says “we’re all a part of each other, each one of us is a part of one another, all of us, everything.” It’s this very theological idea, very similar to the words of Paul when he talks about the body of Christ having many different members but we’re all part of one body. That’s the image that was most in my mind as I worked on it and it’s very central to Wendell’s worldview; it’s very theological and ecological.

The individual is a function of his place and the people around him; you don’t exist but for the others. That’s really profound and important and counter to the way our culture sees individuals now. We have Facebook and Twitter and Instagram and we think every detail we do is important and it’s actually all vanity. Really, who am I without my family, my place, my neighbors? They aren’t just obligation, they are a part of me, they define me. That’s really important to Wendell. He talked to me about that. It’s not about the individual; it’s about the whole community, the membership.

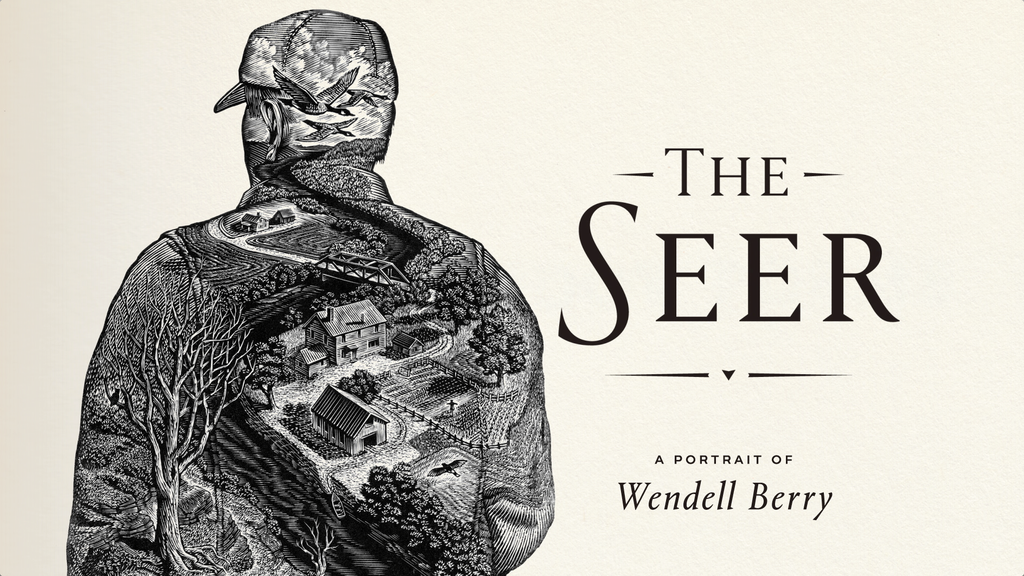

As I approached the film, if you look at that visual image with the man looking away and his back is made up of the landscape, the birds, the clouds, the rivers, the trees, the houses… that’s who Wendell is and his desire to not have it be all about him points us at that very important and significant part of his worldview. To me I still call it a portrait of Wendell Berry because the very way we portray the community is an aspect of something absolutely essential about him, we’re looking at the world through his eyes, not the way the world sees him.

That being said, I thought it was very important in terms of the natural landscape to film across all four seasons, so you’re going back again and again to the same walk down the hills, the same farmhouse, so I think that also trying to film interview lots of different members of the community they really, I didn’t want one voice, I wanted a collection of different voices. So that’s another way we approached it.

Thanks to Laura for taking the time to do this interview! She has six boys and we did the interview while she sat at a park watching them and making sure they didn’t get into too much trouble. (At one point she had to step away to warn one of the boys that there could be poison ivy nearby.) If you like Berry’s fiction, care about environmental issues, or care about traditional ways of life (strong home economies and families especially) you must see this film. You can learn more about it on the film’s website or via the Kickstarter campaign.

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Jake Meador is the editor-in-chief of Mere Orthodoxy. He is a 2010 graduate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he studied English and History. He lives in Lincoln, NE with his wife Joie, their daughter Davy Joy, and sons Wendell, Austin, and Ambrose. Jake's writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Commonweal, Christianity Today, Fare Forward, the University Bookman, Books & Culture, First Things, National Review, Front Porch Republic, and The Run of Play and he has written or contributed to several books, including "In Search of the Common Good," "What Are Christians For?" (both with InterVarsity Press), "A Protestant Christendom?" (with Davenant Press), and "Telling the Stories Right" (with the Front Porch Republic Press).