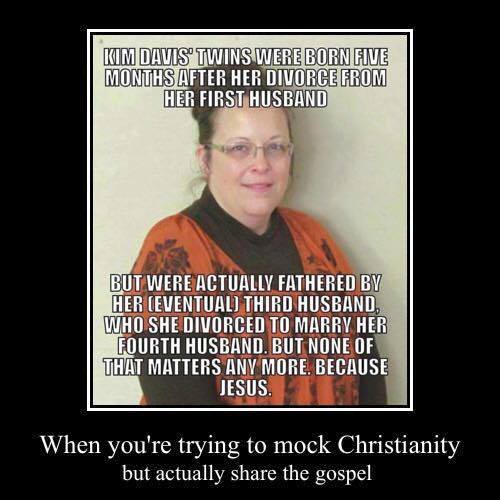

Over at the Federalist Mollie Hemingway has written about Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk refusing to sign same-sex marriage licenses. Many in the media have noted that Davis has been married four times, which certainly calls into question her understanding of natural marriage.

But as Hemingway notes her in her piece, each of Davis’s divorces happened prior to her conversion to Christianity. This doesn’t take away from the tragedy of the divorces, of course, but it puts her opposition to same-sex marriage into a different context. This is not a hypocritical person who wants companionate marriage for me but not for thee. Rather, it is a person who has in the past failed to live up to her marriage vows but has repented of that failure and, as best we know, has been faithful to her vows since her conversion.

You can still disagree with her position, of course. You can, with some reason I think, argue that she has in the past “benefitted” from a companionate understanding of marriage but now does not want other people to benefit in the same way. But you cannot fairly call her a hypocrite. Since adopting the views she now holds she has not gotten divorced. She has been faithful to her beliefs. Disagree, if you like, but lay off the hypocrisy accusations.

But as Hemingway notes, the framing of this story by the media raises other questions as well, specifically it raises questions about how we understand forgiveness and the possibility of personal change:

Yes, Mr. Appelbaum, Ms. Davis has a record of Biblical transgressions. So do we all. She will continue to sin in the years to come. What she has found in her conversion to Christianity, however, is forgiveness of sins. Regardless of the media’s strong views in favor of redefining marriage to include same-sex couples, it would be nice if they took the time to at least understand this central teaching of the Christian faith before attempting to report on it.

This question of forgiveness is not new, of course. It’s one that Matt raised over at the WaPo while discussing online shaming. But as both the various shaming stories and this story of Kim Davis makes plain, we increasingly do not understand what it means to forgive. Indeed, in my darker moments I wonder if forgiveness is increasingly becoming fundamentally incoherent for many people.

The crux of the problem is that forgiveness costs something. Tim Keller made this point well in The Reason for God when attempting to explain the atonement to post-Christian skeptics. In the opening of his chapter on the cross Keller quotes Bonhoeffer who wrote that “My brother’s burden which I must bear is not only his outward lot, his natural characteristics and gifts, but quite literally his sin. And the only wear to bear that sin is by forgiving it in the power of the cross of Christ in which I now share…. Forgiveness is the Christlike suffering which it is the Christian’s duty to bear.”

Traditionally, paying that cost as an individual was tremendously hard, but also made a certain sense. God required it of us and, what’s more, it was often easier to pay the cost of forgiveness than it was to write a person out of our lives because we would rather judge their sin than offer them forgiveness. Our daily experience of the world reinforced the idea of our contingency at every turn. In creation we were reminded of our dependence upon God and in our daily economic lives we were reminded of our dependence on family, friends, and neighbors. So there was a cost to forgiveness, and often a quite great one, but in many cases there was also a felt cost to withholding forgiveness for the simple reason that we were far more dependent on the people we rubbed shoulders with on a day-to-day basis. (Belief in a transcendent divine being who expects us to forgive also creates an obvious pressure to do so.)

You might still choose not to forgive, of course, but it was harder to make that choice because daily contact with a person can make it difficult to generate the sort of sub-human pictures of a person we often create when dealing with a person we refuse to forgive. When you are forced to reckon with the full humanity of a person, as you more easily are when you share a place with them, it is harder to see them in the dehumanized ways we often see those we dislike for long periods of time. (To be sure, the flip side to this is that when a person did choose not to forgive in these situations the fallout was often far messier. Small towns are no idyllic paradise and their citizens are fully capable of vicious sins and proximity can intensify the ugliness of the sin.)

But in an economy increasingly moving toward freelance and short-term contract work in which every person exists only as an isolated, autonomous individual it is not only possible for us to write a person completely out of our life rather than forgive them, in many cases it is preferable. We have ceased to be dependent on individuals except to the extent that (interchangeable) individuals power the many machines that make our world go. Our sense of the self has shifted away from that of a creature embedded in a given order to which we must submit and has moved toward that of the commercial in which we are an independent business entity whose assets include our individual brand which we cultivate through a variety of things, most notably Twitter and LinkedIn.

Relationally speaking, then, forgiveness costs something; cutting ties and “moving on” (telling phrase) is much easier. Indeed, if the predominant way in which we see ourselves today is commercial, then it is not only possible for us to cut ties when a relationship goes south, it is actually advantageous for us to do so in many cases because reconciling would hurt our individual brand.

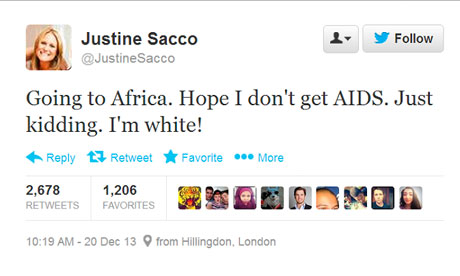

Consider this thought experiment: Suppose after her ill-advised tweet Justine Sacco’s employer said “We know Justine well enough to know that she is a better person than that tweet would suggest and so we will continue to employ her because we care about her, we believe this was a one-time lapse in judgment, and we wish to maintain our relationship with her.”

What would the response be? Well, you don’t have to wonder: What happens to an athlete or celebrity when their brand becomes toxic? They lose sponsors and sometimes lose a job. We can reasonably anticipate something like that happening to Sacco’s PR company as clients would rather cut ties with the company employing Sacco than take the risk of being linked with her.

Thus the cost of forgiveness is simply too great in an excessively commercialized atmosphere. In today’s world we don’t sin; we fail. And failure is not something one forgives but a problem that one solves either by the individual fixing the problem created by their failure through sufficient acts of public penance (so as to restore their brand and perhaps gain points for being “authentic”) or that their partners resolve by cutting ties with the individual while, no doubt, expressing sorrow over the sad direction that individual’s life has gone and confusion about their behavior. (Within this context, Donald Trump’s comments on forgiveness make a certain kind of disturbing sense.)

Consider Matthew Schmitz’s comments about Amazon’s treatment of their workers. For Bezos (and our other fundamentalist technocrats) forgiveness is simply irrational because transgressions are not committed against any sort of recognizable moral order which allows for restitution; rather they are committed against the world-changing work of a given company. And there is a greater cost to allowing the transgressor to stay with the company than there is to sacking them.

Our twin obsessions of purity and efficiency, both of which are divorced from any sort of coherent moral vision, mean that many post-religious folks have adopted a curious form of double separatism that would make the fundamentalist Christians I grew up with (who separated both from apostate churches and from people who did not adequately separate themselves from other “impure” groups) smile with recognition.

The irony of the thing, of course, is that this new cost of forgiveness manufactured by our commercial moment is actually a familiar one to Christians. We worship a God who knows something, after all, of being accused of crimes he did not commit in order to reconcile a relationship with a people he loves. And so this new cost of forgiveness, of being branded as one guilty of sins we have not committed simply because we have forgiven the one who has done those things, is actually a very old cost. And it is one that has already been paid.

Jake Meador is the editor-in-chief of Mere Orthodoxy. He is a 2010 graduate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he studied English and History. He lives in Lincoln, NE with his wife Joie, their daughter Davy Joy, and sons Wendell, Austin, and Ambrose. Jake's writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Commonweal, Christianity Today, Fare Forward, the University Bookman, Books & Culture, First Things, National Review, Front Porch Republic, and The Run of Play and he has written or contributed to several books, including "In Search of the Common Good," "What Are Christians For?" (both with InterVarsity Press), "A Protestant Christendom?" (with Davenant Press), and "Telling the Stories Right" (with the Front Porch Republic Press).

Topics: