Be not afraid.

Thus does Holy Scripture instruct the people of God time and again. In every manner of situation, God or Christ or an angel of the Lord disarms the fright of mere mortals overawed by divine glory or celestial beings or earthly danger. It is a word of consolation meant to inspire confidence by casting away anxieties that well up in the face of threats, actual or potential.

Be not afraid. It is always a good word to hear, for peril is never far from God’s people. But it has been an especially timely reminder these last few months. The refrain has reverberated across the nation, echoing from the lips of pastors to the emails of churches to the articles and tweets of Christian writers and academics.

It is a word well worth echoing. When a fast-spreading but unseen menace threatens the lives of those we love—indeed, the lives of the most vulnerable among us—followers of Christ are right to turn to him as a mighty fortress, a stronghold whose equally invisible hosts protect us against the greater foes we face. The passage from 1 John 4:17-19 is apt: He, the very one who first loved us and gave his life for us, calls us to requite his love with a comprehensiveness that casts out fear. For fear concerns punishment, and Christ, the one who completes our faith, lives to serve and protect us, while he prepares a place for us.

In short, because our faith rests in what we cannot see, our hope does not founder when disaster strikes in this life. Our hope is in the world to come.

For this reason Paul counsels us not to grieve the faithful departed “as others do who have no hope” (1 Thess 4:13). But neither does Paul forbid grieving. Believers are to grieve as those with hope—but to grieve nonetheless. We grieve, rightly, as all do for those taken by death, yet that grief should be marked, stamped, somehow definitively shaped by our unconquerable hope in the day of Christ, and therefore in the promise that those asleep in Christ will rise from their graves and be rejoined to him for eternal life (vv. 14-17). Such hope animates the tears we shed. Our sorrow is pockmarked by the knowledge of the empty tomb, and of so many more to come. Such is specifically Christian sorrow.

In a time of uncertainty and danger, it is worth asking: What if something similar were true of fear? What if fear as such is not to be avoided or prohibited, but only a certain kind of fear? And what if Jesus himself shows us the way here, that is, the way of faithful Christian fear?

For help, I suggest we look to a perhaps surprising guide: the ancient monk St. Maximus the Confessor.

* * *

Maximus lived in the early seventh century. His writings on the agony of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane proved decisive for what came to be called the sixth ecumenical council. His brilliance and holiness rival that of figures as esteemed and influential as Origen, St. Augustine, and St. Thomas Aquinas. He was arrested, exiled, and tortured for his faith, and eventually died of the wounds inflicted on him. Accordingly, he is called a confessor of the church, for under threat of loss of limb and life he made the good confession; and that for which he gave his life—the full humanity and divinity of Jesus Christ—won the day in the decades following his passing.

The controversy that dominated Maximus’s life was whether Christ had one will or two. At first glance this may seem to be a question far removed from global pandemics and human fear, but Maximus knew the gospel of the incarnate God was at stake in it. For the church proclaims what Scripture teaches: that Christ is the Word made flesh, and therefore neither a demi-god, nor God play-acting as man, nor still a hybrid offspring like Hercules. No, he is very God and very man, one person in two natures.

But to be God is to will as God, and to be human is to will as a human. Human willing is one thing, divine willing another. Will seems to follow nature, what one is. What then of Christ?

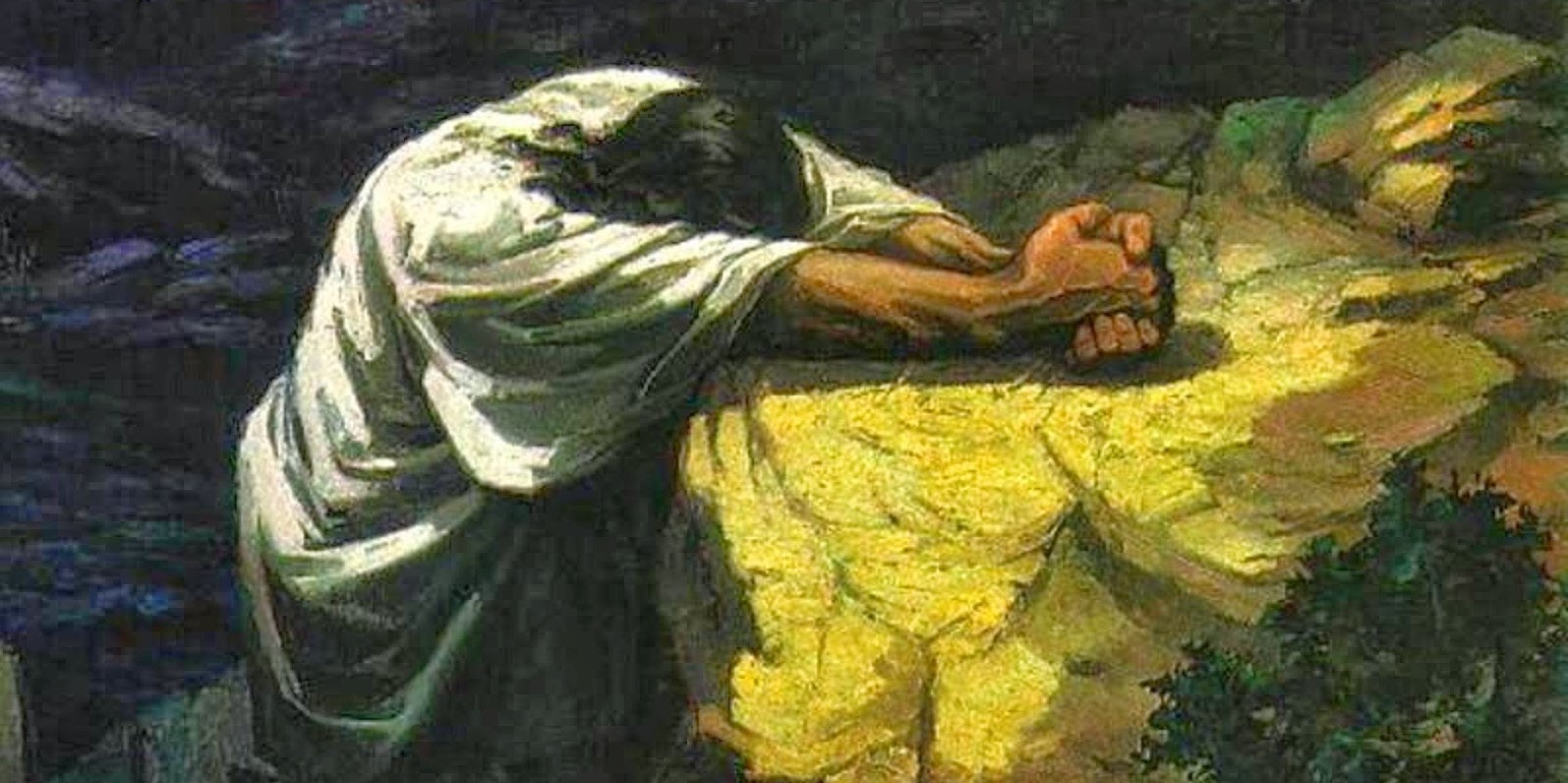

Maximus affirmed that Christ indeed had two wills, in accordance with his two natures. The very text that his opponents took to prove the contrary view Maximus understood to demonstrate his point. For in the Garden, on the night when he was betrayed, Christ prayed to the Father that he might remove the cup of suffering, “but not my will but thine be done.” Far from opposition, there is a conformity of wills in the prayer of Christ: the perfect unity of his human will with the divine will; and that very unity manifests the presence of both wills in the one person of Christ, God the Son become the Son of Man. He wills divinely as man to suffer and die for our sake; he wills humanly as God to shrink before death, in solidarity with our flesh, so as to purify the passions by subjecting them to the divine resolve to save us from the wages of sin.

In other words, what we see in the Garden is not for show. It is not fantasy or fiction. Christ, because he is truly and naturally human, fears death the way any bodily creature might: for to be destroyed is not good, does not belong to an unfallen world. His humanity recoils from the prospect of the passion, not out of lack of trust in the Father or uncertainty in his vocation, but because he is like unto us in every respect apart from sin. As God with us, he is one of us. And it is only human to shrink before death, even death on a cross.

But Maximus wants us to see that that is not the end of the story, because Christ’s solidarity with us is always redemptive, and so it is here, too. His fear is part of his saving work in that it is exemplary for us. For, far from obstructing his obedience to God, Christ’s natural fear becomes the occasion for it. “Not my will but thine” is the cry of a heart faithful to God in the presence of fear, not in its absence. It is the cry of courage, which is the virtue that knows the right thing to do, and wills to do it, when disavowal of fear would mean self-deception or recklessness. In this Jesus is our pioneer, the trailblazer of truly human courage, precisely in that moment when fearlessness would be foolish. For the will of the Lord outbids even our rational fears.

In this way, Maximus helps us to see what Christian fear might mean. All of Christ’s action is our instruction, as Aquinas says. Here too: we live as Christ lived, die as he died, suffer as he suffered, fear as he feared. If we are to grieve as those with hope, but still to grieve, so are we to fear as those with faith, but still to fear.

* * *

What then of Coronavirus? Let me reaffirm what I said at the beginning: Christians are not to be defined or determined by our fears. The Lord reigns, and our hope is hid with Christ in heaven (Col 3:3). Loss of earthly life, however terrible, is not the last word for those baptized into the death and resurrection of Christ. His triumph over death means we have been liberated from the terrible bondage in which all are held who live in perpetual fear of death, as Hebrews 2:14-15 teaches.

But as the subsequent verses go on to say, “because he himself has suffered and been tempted, he is able to help those who are tempted” (2:18). Maximus simply glosses this verse with a view to Christ’s humanity and the passions of the flesh he assumed in the incarnation, following Hebrews 5:7: “In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to him who was able to save him from death, and he was heard for his godly fear.”

It is godly fear—reverent unease, pious trepidation—to which we are called in this time. Now in context, the primary sense of this term is that fear of the Lord which is the beginning of wisdom. But given the allusion to Jesus’s cries and tears in the Garden, and the unstated object of his fear, we have reason to suppose the term’s reference encompasses Jesus’s natural but not disproportionate fear of what was to take place on Good Friday. Put differently, his fear of death was encompassed by his fear of God. And the latter phrase is only another name for faith.

The upshot? Jesus was not a ghost or an apparition. His body was as real as yours and mine, with all its needs and desires and vulnerabilities. When the hour had at last come, he did not flinch, did not doubt or flee. But he did fall to his knees. His flesh, as Maximus puts it, shrank before death. But that is what flesh does. “For the Spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak” (Mark 14:38). He assumed our weakness, but not for nothing. He showed us the way of holy weakness. What Christ spoke to Paul applies preeminently to himself in the Passion: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor 12:9). As Christ was mightiest to save at his lowest moment, so are we strongest when our weakness is most pronounced.

It is okay, in other words, to be afraid. Fear of death is natural. It is not sinful or unbelieving. It does not mean one’s faith is lacking, any more than grief at the loss of a loved one means one’s hope is lacking. It is how we fear, not whether we fear, that marks us as Christ’s. Our flesh shrinks before this virus wreaking so much havoc on the world. But we are not only flesh. We are Christ’s body, filled with his Spirit. When fear threatens to be more than an instinctual recoil at death—that final enemy of God the Father (1 Cor 15:26), despoiled by his Son, who now holds the trophies of plunder, the keys of Death and Hades, in his hands (Rev 1:18)—when fear tempts us to despair or greed or inaction, then we look to Christ in the Garden, and remember.

Remembering, we unite our fears to his, and submit it in prayer to God, who is his Father and ours. Praying, we join our wills to his, begging the good pleasure of God to be done, on earth as it is in heaven. And with groans beyond words, the Spirit of him who raised Christ from the dead, who knows the mind of God, intercedes on our behalf in accordance with God’s will (Rom 8:26-27).

This is Christian fear in action. It is the courage of faith in the face of fear. In the Gethsemane of a global pandemic, the people of God know that agony may bring us to our knees. But it is there above all where we find Christ. He is not ashamed to share our condition. He condescends even to our fears. We therefore need not hesitate to join him there, in the Garden where death’s shadow lies. For if we kneel with him, he will raise us up.

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Brad East (PhD, Yale University) is assistant professor of theology in the College of Biblical Studies at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. He is the editor of Robert Jenson’s The Triune Story: Collected Essays on Scripture (Oxford University Press, 2019) and the author of The Doctrine of Scripture (Cascade, 2021) and The Church’s Book: Theology of Scripture in Ecclesial Context (Eerdmans, 2022). His articles have been published in Modern Theology, International Journal of Systematic Theology, Scottish Journal of Theology, Journal of Theological Interpretation, Anglican Theological Review, Pro Ecclesia, Political Theology, Restoration Quarterly, and The Other Journal; his essays and reviews have appeared in The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Comment, Commonweal, First Things, The Hedgehog Review, Living Church, Los Angeles Review of Books, Marginalia Review of Books, Mere Orthodoxy, The New Atlantis, Plough, and The Point. Further information, as well as his blog, can be found at bradeast.org.

Topics: