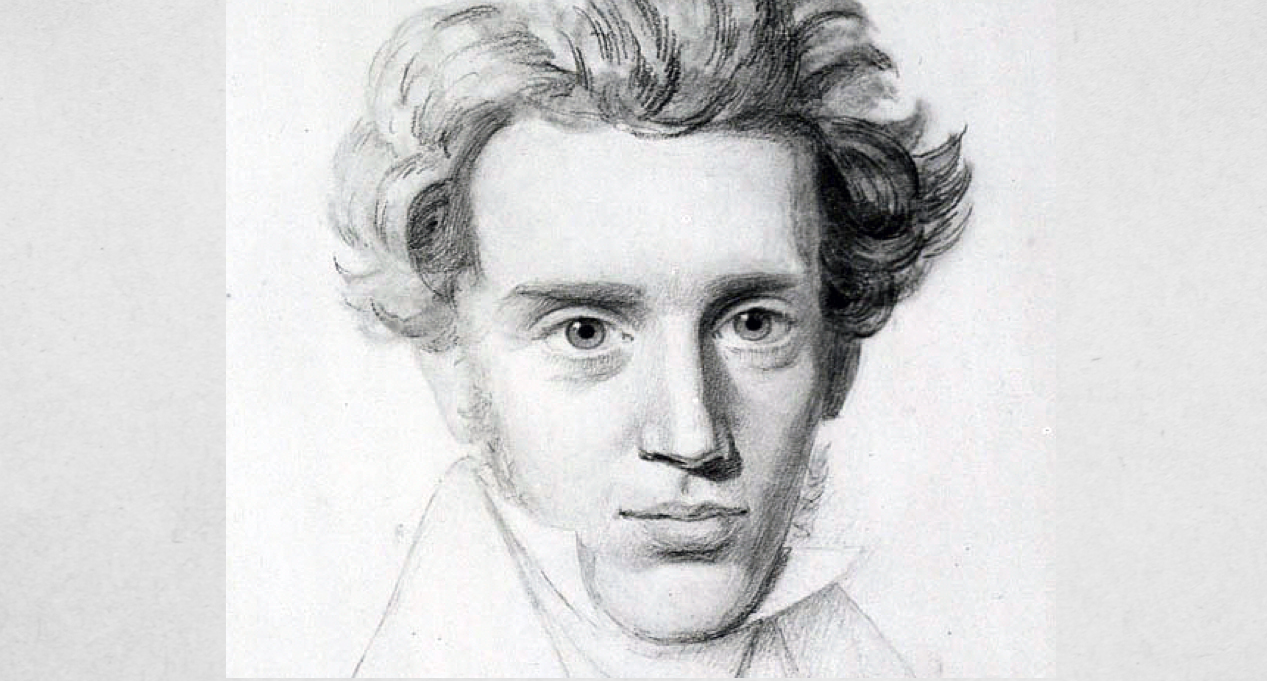

Søren Kierkegaard still makes people either love him or hate him. Even many who have dedicated their life’s work to studying his authorship approach him biographically with either veneration or suspicion. Some biographies offer rather seraphic portraits of Kierkegaard, whereas even in his personal life others see only masks that impishly conceal more than they reveal. They question Kierkegaard’s sincerity and wonder if he has left us anything about his true identity but a hopeless hall of mirrors.

Despite their various approaches, Kierkegaard’s biographers all agree that he was a complicated figure who lived an unconventional life and authored one of the most eccentric corpuses in the history of theology and philosophy. What makes Clare Carlisle’s new biography of Kierkegaard unique is her disposition toward him. Rather than emphasizing either his deviance or his saintliness, Carlisle foregrounds his humanness. Setting both airbrush and sideways glance aside, her “Kierkegaardian biography” of Kierkegaard is what he himself would designate a work of love.

Carlisle is not after a biography that considers Kierkegaard’s life from the perspective of a detached spectator, but one that “joins him on his journey and confronts its uncertainties with him” (xiii). She has good Kierkegaardian reasons for such an approach. For “just as we cannot step off the train while it is moving,” she writes, “so we cannot step away from life to reflect on its meaning” (xiii).

Thus, a Kierkegaardian biography of Kierkegaard entails “following the blurry, fluid lines between [his] life and writing, and allowing philosophical and spiritual questions to animate the events, decisions and encounters that constitute the facts of a life” (xiii).

What you will not find in her text is a catalogue of facts arranged in sequence and understood rather straightforwardly. What you will find is an account that is both carefully researched and imaginative, one that introduces Kierkegaard as a living subject. The objective facts of his life, the development of his thought, and his subjective person are inseparable for Carlisle. The actions, events, people, places, ideas, and experiences that stood in important relation to him formed an ensemble that shaped the kind of person he became. Carlisle attends carefully to who this person was, and holds him – warts and all – in loving regard. According to Kierkegaard’s own pen, that is what the gaze of love does.

In Works of Love, Kierkegaard writes, “To be able to love a person despite his weaknesses and defects and imperfections is still not perfect love, but rather this, to be able to find him lovable despite and with his weaknesses and defects and imperfections.”[1]

Love requires a kind of seeing, one that occupies itself with noticing and regarding the concrete givenness of the actual other. It sees the other as a neighbor, one who is uniquely created by God. The work of love is not to be a “sin sleuth” whose job it is to unearth faults in the other. A sin sleuth gazes at the other with mistrust and suspicion, which Kierkegaard insists conceals more than it reveals.

Even worse, the sleuth’s suspicion malforms her own selfhood by deceiving her out of love.[2] Rather than relating to the world with a disposition of love, the self sweeps for faults in the other and rejoices when she finds them.

Just as it is not to be a sin finder, the work of love is also not to be a sin denier. It does not look at the other through a pair of rose colored glasses or a willful denial of someone’s faults. Instead, it is convinced that “even though it is not seen – indeed, even though the opposite is seen – [love] is still present in the ground, even in the misguided, even in the corrupted, even in the most hateful.”[3] In other words, love recognizes the other as always caught up in God’s good purposes, no matter what sorts of faults he or she might have. Love enlarges the horizon within which we see our neighbor, and for that reason it is never deceived. Seeing the concrete other in both her strengths and weaknesses, love hopes all things and believes all things for her. This is exactly what Carlisle does for Kierkegaard.

Carlisle travels alongside Kierkegaard, accompanying him both on the mountain tops and in the valleys of his life experiences. She admits, “Kierkegaard is not an easy travelling companion, though he was by many accounts charming, funny and compassionate as well as endlessly entertaining” (xiv). This is a fitting description of the reader’s experience as well. There are times when Kierkegaard is alluring and fascinating and other times when he is frustrating and downright unlikable. He demonstrates great sensitivity to others, not just in his psychological insight but in his tenderness toward seekers and sufferers.

Yet, just as soon as he warms your heart, you then read of the petty spats he instigated with Hans Christian Andersen, his visceral reactions to the editors of The Corsair and various leaders in the Danish State Church. Throughout his life Kierkegaard resorts to cruel backbiting. At times, his tactics seem to be driven more by envy and an obsession with his own self-image than a pure desire to see Christianity saved from nominal Christendom. What Carlisle brings out is that both are true of Kierkegaard: he was complex and fragile, sincere and unsure, inspired and broken, sensitive and incisive. His mind was sharp and so was his wit – which was both a blessing and a curse.

More often than not, Kierkegaard philosophized and theologized from a broken heart. Carlisle focuses especially on the way his work was animated by his relationship to Regine Olsen throughout the years. From the time he met Regine, he struggled with what seemed to be conflicting desires. He desired a life with her, but he wondered if that prospect was a temptation rather than a gift from God. He feared it would take him away from his calling rather than help him expand in it.

Kierkegaard eventually concluded that faithfulness to God did not mean leaving the world behind, but rather dwelling in the finite world coram Deo. As he says, a human being’s true life “does not mean stealing out of finitude to become volatilized and evaporated on the way to heaven, but rather that the divine inhabits the finite and finds its way in it.”[4] He thus decided to pursue Regine. Despite a rather awkward proposal, she agreed to marry him.

Soon after, the inner conflict returned, and this time got the upper hand. He decided to break off the engagement. Regine fought against him “like a lioness” and Kierkegaard suffered from the pain of hurting someone he so deeply loved. He decided that the best way to make things easier for her was to feign indifference; to pretend that he did not love her, and that he never did. He would rather be hated by her and others than let her feel publicly humiliated and personally rejected. It was from this experience that he created the character of Johannes the Seducer in Either/Or. Personally, Johannes is a mask he puts on to feign his indifference for Regine. Philosophically, Johannes represents what Kierkegaard calls the “aesthetic” stage of existence, and his counterpart, Judge William, represents the ethical stage.

Kierkegaard uses romantic relationships as a way of getting at deeper structures of existence. Describing the way Johannes the Seducer looks down upon his own existence, surveying it with a God’s-eye view, Carlisle writes,

Perhaps Kierkegaard himself had lived like this before his engagement crisis – always outside himself, hovering above his world. And then he was shipwrecked on the warm-blooded, irrefutable existence of a young woman who lived a few streets away, who loved him and expected to marry him, whose eyes gazed directly into his own, whose tears he could reach out and touch. From Regine he learned that no philosophical system, no merely intellectual approach to life, helps a human being to live in the world, to make decisions, to become himself (137).

Using romantic love as a means of exploring the nature of the self’s relation to reality more generally is one of Kierkegaard’s signature techniques. Not only does it prove useful for gaining philosophical and theological insight, but also demonstrates that romantic love was a painfully unresolved issue for him.

According to Carlisle, Kierkegaard staged the drama a bit differently in Fear and Trembling and Repetition. While Hegelian philosophy and its theological import by Hans Lassen Martensen was undoubtedly a target of his account of Genesis 22, the book was also about Regine. He gave up his show of indifference to Regine. Instead, she was to Kierkegaard what Isaac was to Abraham. He later realized that he was the Knight of Infinite Resignation, the one who let go of the finite world but could not receive it back in faith as a gift from God. “If I had faith, I would have stayed with Regine,” he later lamented.

His work Repetition is another example of how Kierkegaard wrote in a way that was intensely personal and philosophically profound at the same time. In the text, he develops a philosophical category, one that I believe is still largely untapped as a resource. He also battles his own inner conflict about life without Regine. Embedded in the story are snide comments about how the young man’s beloved is not particularly special, and Carlisle shows how Kierkegaard’s corresponding journal entries are riddled with self-justifying complaints about Regine’s “pride” and “arrogance” throughout the ordeal.

Soon after, Kierkegaard learned of Regine’s engagement to government official Johan Frederick Schlegel. Furious, he wrote out imagined chance encounters with her wherein he would slight her in some way – one of his more unlikeable moments. However, the event drove him back to his draft of Repetition to change the ending. Carlisle explains,

Instead of killing himself in despair of becoming a suitable husband, the book’s young hero learns that his beloved is engaged to someone else; this unexpected news liberates him from his crisis of identity, and he thanks God for granting him his freedom – here, at last, is the ‘repetition’ he has longed for. Once again, his future lies open before him; he has another chance to choose his path in life (168).

The ending of one possibility that always loomed over him served to open up new ones. This moment was like a dawning of consciousness for him, one that summoned him into his vocation more fully.

In the following years Kierkegaard cultivated his vocation and identity as a writer. He was animated by a desire to see the Danish people awaken from nominal complacency to earnest existence before God. He continued to work from his close acquaintance with grief. Carlisle writes, “Kierkegaard’s work of soul-searching, exploring his own anxiety and suffering, has deepened his understanding of being human, giving his philosophy a power to affect others. He lives this philosophy inwardly, often painfully, and expresses it in his relationships to those closest to him” (179).

In his later writings, Kierkegaard further developed his ideas of suffering, concluding against the Abraham of Fear and Trembling that this life is all loss. For the Christian, he concluded, there can be no embrace of the finite world, only dying to it. His loathing of the “comfortable Christianity” preached from the pulpit of the Danish State Church stoked the coals of this conviction. According to Carlisle, however, one thing that gave him pause was Regine. At the time they frequently passed one another in the streets. These distant encounters communicated a deep, unspoken reconciliation between them that Carlisle suggests was an anchor in Kierkegaard’s world (239).

In his journal, Kierkegaard recognizes that Regine has no inkling of the kind of radical Christianity he longs to see. If he were to embrace it fully it would create a religious difference between them, a thought he could not bear. However, in 1855, Schlegel took the office of Governor of the West Indian Islands, and Regine left Denmark with her husband. Kierkegaard lost his anchor, the rootedness in finitude that she had always been for him. At this point, he decided to launch his full-on attack against the Danish State Church.

There are many ways that Kierkegaard’s final years contradicted his earlier ones both in his method, and at times, his message. The indirect communicator who wrote in pseudonyms and recognized the limits of what one person can do for another promoted his subversive message in ways that were direct and obnoxious. Carlisle speaks of his rants in daily newspapers and public displays of boycotting Church attendance. The only kind of subversive Christianity Kierkegaard could imagine in his later years was one that dies to the world. Yet it was the kind he envisioned in his earlier years that, I suggest, was truly subversive: one that dies to the ultimacy of the world, and then dwells within the finite as a gift.

Though his thought owes much to many tussles with contemporary thinkers and inspiration from teachers and the places, Carlisle shows how it was not only his ideas, but his general disposition and his tactics that were tied to the unfolding dynamics of his relationship with Regine. Old wounds birthed new ideas. Grief both softened and soured him in old age. Unhappy love agonized his heart, but it also sharpened his eye for truth and subjectivity.

While refusing to follow the linear progression typical of biographical accounts is consistent with the Kierkegaardian approach Carlisle hopes to achieve, it also causes her work’s greatest weakness. She rightly notes,

“Our past and future are vibrant inside us. We do not experience time as an external framework or a linear sequence, like a train track on which our lives run. While we move inexorably forward, breath by breath and heartbeat by heartbeat, we circle back in recollection and race ahead of ourselves in hopes, fears, and plans. By these looping, stretching movements we shape our souls, make sense of our lives – and this is precisely what I found Kierkegaard doing in his journals” (xiv).

The idea, however, is perhaps more clever than the execution.

As she flips back and forth in time and to various scenes, it can be difficult to follow her lead, especially for a reader who is unfamiliar with Kierkegaard’s life and works. Her explanation of particular texts in his authorship is accessible and clearly connected to the context of his life. The summaries of Fear and Trembling and Repetition are especially masterful, which is unsurprising given the fact that she has written two monographs on those particular texts.

However, new readers would benefit from having at least an introductory understanding of his life and works before approaching Carlisle’s work. When they do, they will find that she integrates the pieces of Kierkegaard’s life and thought in a way that brings them as close to the person as research and imagination allow. She follows his life not as an indifferent spectator taking it in from the outside, but alongside him with both the patience and the hope of neighborly love.

At the end of her biography, Carlisle includes a picture of herself standing at Kierkegaard’s graveside reading the lyrics of a hymn by Hans Adolph Brorson he requested to be engraved on his tombstone. Despite his tossings, these words express what always remained the ever-fixed mark in Kierkegaard’s life:

In yet a little while

I shall have won;

Then the whole fight

Will all at once be done.

Then I may rest

In bowers of roses

And perpetually

And perpetually

Speak with my Jesus.

The Philosopher of the Heart, as Carlisle affectionately calls him, earnestly sought to live a faithful life before God, to rest transparently in the Power that established him, and to build up others in their quest to do the same. Faith was a task of a lifetime for Kierkegaard, and it was one that he remained true to all the way to the end.

Enjoy the article? Pay the writer.

Footnotes

- Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), 158. ↑

- Kierkegaard, Works of Love, 235. ↑

- Kierkegaard, Works of Love, 221. ↑

- Søren Kierkegaard, A human being’s ‘true life:’ Søren Kierkegaard’s Journal and Papers, pp. 213-124: Pap. III A I (July 4, 1840). ↑

Topics: